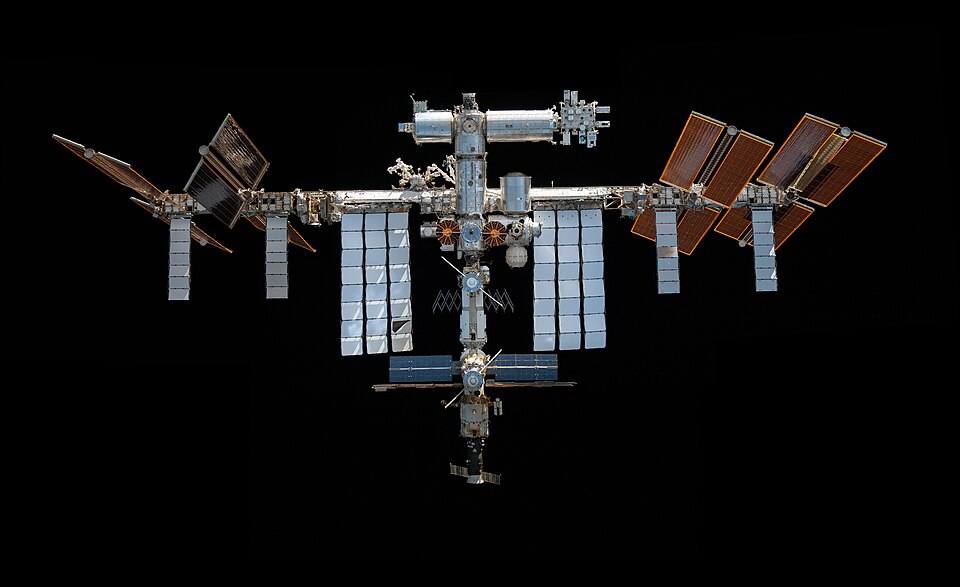

The International Space Station is still busy, still productive, and still crowded with cargo and crew traffic. But its role as humanity’s default home in low Earth orbit is already being redesigned this time around contracts, service-level agreements, and customers who are not all government astronauts.

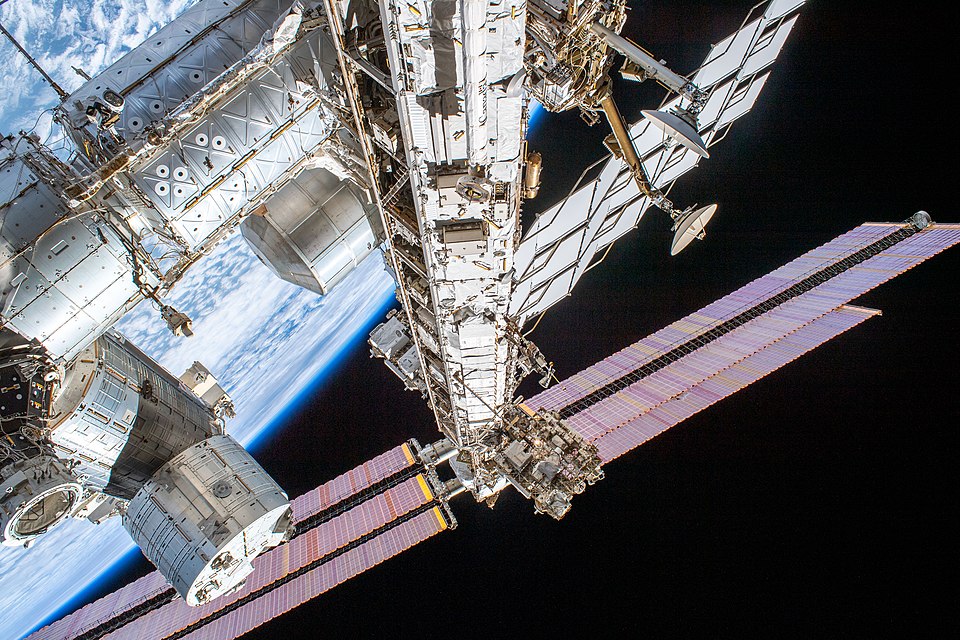

That shift is set to sharpen in 2026, when NASA plans to move from nurturing station concepts to buying down risk on real hardware. The technical story is less about shiny new modules than about whether industry can deliver power, life support, safety processes, and launch cadence that feel routine because routine is the entire point of having an orbital “place” again.

1. NASA’s 2026 procurement pivot for commercial stations

NASA’s low Earth orbit plan explicitly treats the ISS as a program with an end date and treats its successor as a marketplace. The agency says it will issue a Phase 2 Announcement for Proposal in late 2025 and aims to award multiple funded Space Act Agreements in early 2026. Those awards are structured around milestone payments and include, at minimum, progress to critical design review readiness and an initial in-space crewed demonstration.

This is a subtle engineering signal: NASA is no longer primarily buying a destination; it is buying evidence. Hardware must prove it can keep people alive, keep experiments stable, and keep interfaces standardized enough that “NASA as one customer among many” is plausible. The ISS was built as an international project first and a lab second; commercial stations reverse that order by making utilization the steady, mundane throughput of experiments and crews the core design driver.

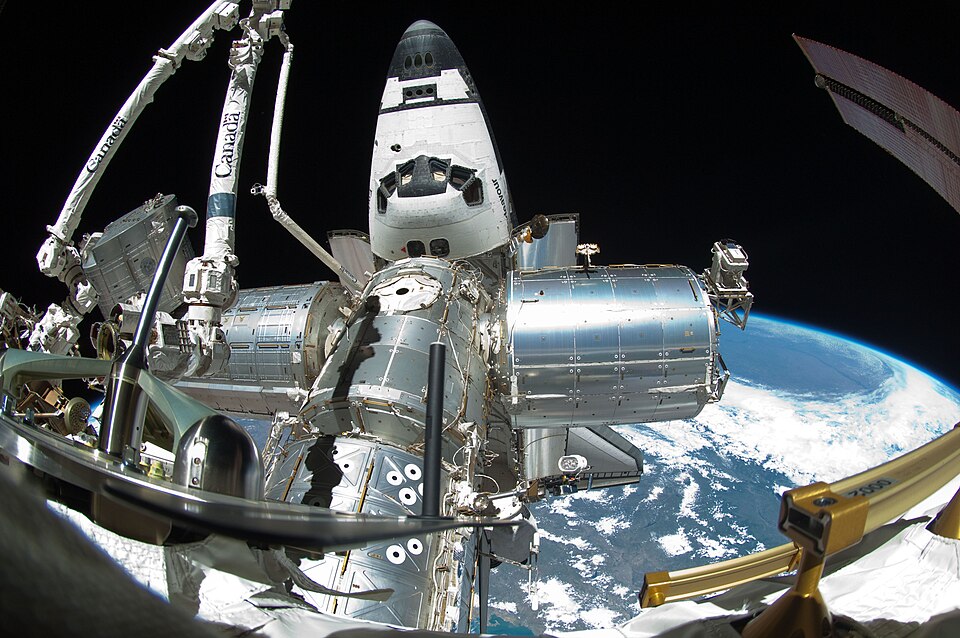

2. The ISS-to-commercial bridge: Axiom’s attached module strategy

Among the commercial approaches NASA has already blessed, Axiom’s stands out for treating the ISS as both landlord and test stand. NASA awarded Axiom Space a contract in 2020 to provide at least one habitable commercial module that attaches to the ISS, with the goal of becoming a free-flying station before the ISS retires.

Engineering-wise, “attach first, detach later” reduces the number of firsts that must happen on day one: power and thermal behaviors can be validated while the ISS remains the backstop. It also forces compatibility with existing docking, crew procedures, and safety reviews constraints that are annoying in the short term, but valuable if the long-term objective is a plug-and-play LEO economy rather than a bespoke outpost.

3. Starlab and Orbital Reef: designing for customers beyond NASA

NASA’s earlier Space Act Agreements helped seed multiple station designs, including Blue Origin’s Orbital Reef and the Starlab effort (after Northrop Grumman withdrew from its own agreement and joined Starlab). The common engineering challenge is not simply volume; it is operations. Stations are not just pressure vessels with windows stations are logistics schedules, spares philosophies, environmental control loops, and fault responses that must work at 3 a.m. without improvisation.

The commercial bet is that a station can be engineered like infrastructure rather than like a flagship mission: standardized experiment racks, predictable crew time, and enough power and data margin that new users do not have to negotiate for every watt. That requirement pushes designs toward maintainability and modular replacement, because downtime is the one thing a “station as a service” business model cannot hide.

4. Artemis II’s timing pressure: LEO as the proving ground again

While LEO reorganizes, NASA’s next crewed lunar mission continues to act as the cultural metronome for human spaceflight. NASA describes Artemis II as a “No Later Than April 2026” mission to send four astronauts around the Moon on a 10-day flight, confirming Orion’s systems with crew aboard in deep space.

That schedule matters in LEO for a pragmatic reason: the more NASA leans into deep-space missions, the more it needs LEO to keep doing what it does best training, microgravity research, and long-duration systems validation without NASA having to own the platform. Commercial stations inherit the unglamorous responsibility of being the place where life support hardware earns trust through repetition.

5. Starship’s heat shield reality check and why LEO infrastructure cares

Ambitious LEO destinations are only as real as the transportation system that feeds them. SpaceX’s Starship development, for example, keeps surfacing the kind of details that quietly decide whether high-cadence operations are feasible. SpaceX reliability executive Bill Gerstenmaier summarized a recent experiment succinctly: “The metal tiles didn’t work so well.” He also highlighted an experimental sealing approach: “We call it crunch wrap.”

Those quotes land directly on the commercial-station problem set. Station operators need predictable cargo upmass, predictable crew rotation, and predictable return capacity for samples and hardware. Reusability is not marketing; it is schedule stability. When reentry protection is still evolving tile-by-tile, everything downstream inventory levels on orbit, experiment turnarounds, even how much emergency margin a station must carry gets harder.

In practice, “goodbye to the ISS” is not a single moment. It is a gradual transfer of responsibilities: NASA moving from owner-operator to anchor tenant, and industry moving from proposals to demonstrated life-support, safety, and operations. By the end of 2026, the most important change in low Earth orbit may be procedural rather than physical: the point at which station capability is measured less by what it is called and more by what it can reliably deliver, week after week.