What does it take to keep track of an oil tanker that can change its name, its flag, and even the location it appears to occupy on maritime trackers? The recent U.S. boardings of two sanctioned tankers one pursued into the North Atlantic and another intercepted near the Caribbean have drawn attention inside maritime engineering circles for a different reason: the mechanics of concealment at sea, and the tools used to pierce it.

The vessels were described by U.S. officials as part of a “ghost” or “dark” fleet moving sanctioned oil. For ship operators, insurers, port-state authorities, and maritime domain awareness teams, the episodes function as a high-profile case study in how identity and location are managed on modern commercial vessels and how those claims can unravel under technical scrutiny.

1. Mid-voyage renaming and reflagging

The tanker pursued across the Atlantic was identified by U.S. officials as Bella-1, later operating as Marinera and sailing under a Russian flag. Analysts cited in the BBC noted that changing a vessel’s flag during a voyage is not a routine administrative update and can be treated as irregular when the underlying registry transfer is unclear.

The practical point for enforcement and compliance teams is that painted markings and declared flags can change faster than a ship’s deeper identifiers, including its International Maritime Organization (IMO) number and ownership/control networks.

2. “Stateless” as an enforcement hinge

Whether a ship is considered properly flagged or effectively without nationality can determine what kinds of boardings are available under international maritime practice. The White House described the Atlantic-pursued ship as “deemed stateless after flying a false flag”. A separate legal analysis of earlier seizures explained how the law-of-the-sea concept of statelessness can remove the usual barrier of exclusive flag-state jurisdiction on the high seas, expanding boarding authority while leaving debate over the scope of subsequent enforcement actions.

3. AIS “spoofing” and the limits of self-reported position

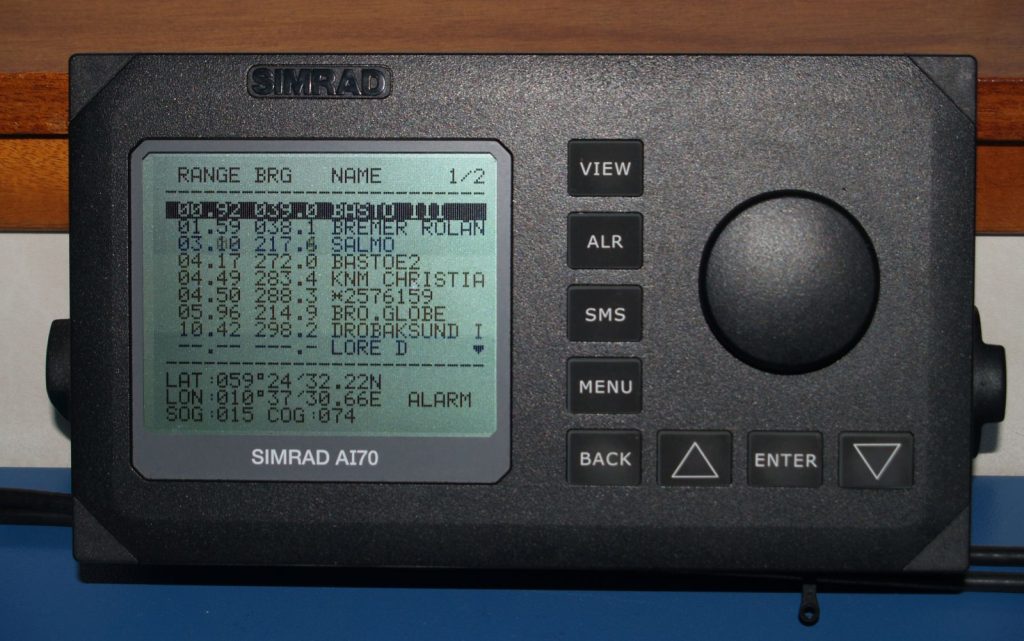

Automatic Identification System (AIS) data underpins collision avoidance, traffic management, and much of the public ship-tracking ecosystem. But dark-fleet operators have manipulated it. One technical explanation described “spoofing,” where a vessel broadcasts a false location instead of its real-time coordinates. Analysts cited satellite imagery as a counterweight: when imagery places a ship near one coastline while AIS claims another, the discrepancy becomes a strong indicator of deliberate deception.

4. “Dark mode” operations: going silent

Beyond spoofing, tankers can reduce traceability by shutting off or ceasing transmission of tracking signals. In the current cases, officials characterized the second tanker as a “stateless, sanctioned dark fleet motor tanker,” while outside analysts described patterns of operation with transponders off for sanctioned movements. The engineering takeaway is straightforward: systems designed for safety and transparency can be degraded by operator choice, shifting the burden to radar, satellite, aerial surveillance, and port intelligence to fill gaps.

5. Helicopter boarding as a maritime access method

Video released by U.S. authorities showed helicopters approaching large tankers and personnel landing on deck. Russia’s state broadcaster RT also published imagery of a helicopter near the Atlantic vessel. For naval architects and marine operators, this highlights a reality of modern interdictions: vertical insertion bypasses ladders, pilot stations, or cooperative boarding arrangements. It also places attention on deck layout, obstructions, rotor-wash hazards, and safe access routes to the bridge details that sit at the intersection of ship design, seamanship, and security operations.

6. Multinational support and wide-area tracking

Operational support reportedly included logistical help by air and sea from the UK, alongside U.S. Coast Guard and military assets. A two-week pursuit across the Atlantic illustrates the enabling layer behind a boarding: cueing from multiple sensors, sustained presence, and coordination across commands and partners. In practice, wide-area maritime domain awareness increasingly depends on fusing AIS (trusted or not), commercial satellite imagery, aircraft surveillance, and shipping-industry data such as port lineups and broker information.

Across both seizures, the recurring theme is that “identity” at sea has become a stack: paint and paperwork at the surface, radio broadcasts in the middle, and deeper technical and network identifiers underneath. The more frequently a vessel’s outward profile changes, the more attention shifts to those harder-to-alter layers.

For the broader maritime industry, the episodes underline a persistent engineering and governance challenge: global shipping runs on interoperable systems built for safety and commerce, while a growing set of operators treat the same systems as variables to be manipulated. The contest now turns on detection fidelity how quickly inconsistent signals can be isolated, verified, and acted upon.