“Choosing the “best” Army sidearm usually devolves into a caliber argument inside 30 seconds. A more useful question is which handguns actually changed the way the Army armed, trained, and equipped its people – because influence leaves a paper trail in procurement decisions, doctrine, maintenance realities, and what stayed in the holster long after the next model arrived.

Dozens of sidearms have cycled through Army service over the years, but only a few became true points of reference: designs which set expectations for reliability, capacity, ergonomics, or industrial scalability. The following five earn their place by shaping what “standard issue” meant in their era, and for creating downstream effects that showed up in later programs and test standards.

1. Colt M1911 / M1911A1 .45 ACP

The influence of the M1911 begins with the Army’s early-20th-century pivot away from revolvers toward a service-wide semiautomatic pistol-and then continues for the better part of a century. Adopted in 1911 after a competitive trial period, the pistol introduced a durable locked-breech design, a single-action trigger system, and a cartridge that the Army had decided should be no smaller than .45 caliber for a military handgun. That caliber decision was reinforced in the era’s testing culture and became a lasting reference point in American handgun debates, even as later research complicated simplistic “stopping power” claims.

What made the M1911 mechanically influential was not just the cartridge but how it packaged reliability, maintainability, and shootability into a sidearm that could be built at scale. That mattered because Army handguns are logistical objects as much as fighting tools-serialized, inspected, repaired, and passed between users for decades. The later revisions in 1926, the M1911A1-small ergonomic changes like the arched mainspring housing and improved sights-show how the platform could be tuned without breaking its core architecture.

The afterlife of the 1911 pattern was thus unusually long, even after its official replacement. The platform had become a benchmark both in training culture and in procurement requirements alike, continuing in limited roles long after the era of standard-issue had ended. That form of institutional inertia is one form of influence: the pistol was not merely carried, it was used as a measuring stick for what came next.

2. Beretta 92F/92FS as M9 (9×19mm)

The modern Army pistol procurement visibly becomes “systems engineering” during the M9 era. The reality driving the Joint Service push for handgun standardization was that the U.S. inventory had become a sprawling mix of models and ammunition types, forcing logistics to solve problems it should never have had to own. This emphasis drove requirements to include 9×19mm for NATO alignment, double-action/single-action operation, and higher capacity-an explicit move away from the 7-round single-action .45 template that had defined the previous generation.

In testing, the Beretta design posted stand-out reliability metrics-measured in mean rounds between failure-and then won on total package cost in the final head-to-head procurement. The M9’s influence shows up in the next several decades of expectations: a 15-round magazine became the new normal, and the “shootability” advantages of 9mm-particularly for less experienced shooters-became inseparable from the training and qualification ecosystem that surrounded the pistol.

Equally important, the M9 became a case study in lifecycle management. The platform’s reputation was shaped as much by maintenance discipline and parts replacement intervals as by inherent design traits. In extended service, small components like recoil springs and locking blocks turned into readiness drivers-an engineer’s reminder that “reliability” is not a single number from a trial but a relationship between design, supply chain, inspection, and user behavior. The later adoption of the railed M9A1 configuration underlined how lights and accessory mounting became non-negotiable features for a modern service pistol.

3. SIG Sauer M11 – P228 variant

The M11 is influential precisely because it was not the big iconic “everybody gets one” handgun; it represents the Army acknowledging that a one-size service pistol does not cover every role, then institutionalizing a compact, high-quality option for investigative and protective missions. Adopted under the Compact Pistol Program, the M11 provided a smaller footprint than the M9 while retaining the 9mm chambering and a double-action operating concept that meshed with the broader safety and handling expectations of the period.

Its deeper consequence was how it normalized specialized handgun procurement inside a standardization era. The long service of the M11 with Army Criminal Investigation Division and other niche users showed that the Army could maintain a parallel pistol line without collapsing back into the pre-standardization chaos of dozens of incompatible models. It also reinforced the idea that the reliability validation is a long game: endurance firing and low malfunction rates mattered more than novelty.

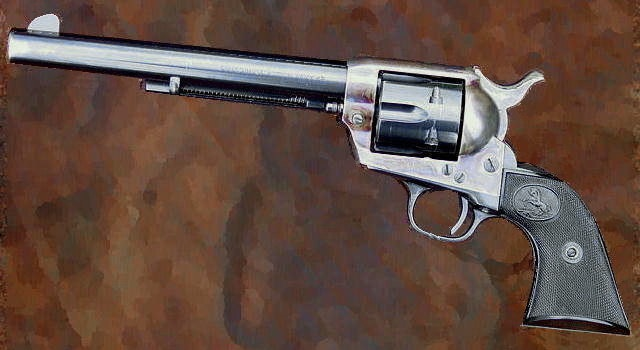

4. Colt Single Action Army “Peacemaker” Model 1873, .45 Colt

Few Army handguns left a larger cultural footprint than the Model 1873 Single Action Army, but its technical influence is equally real. Arriving as the Army was transitioning to metallic-cartridge revolvers, it delivered a robust frame and a powerful service cartridge in a package that could tolerate harsh field conditions and inconsistent maintenance. It would prove, in an institutional sense, a durable answer to the post-Civil War question: what does a standard sidearm look like when ammunition is selfcontained and the revolver is no longer a percussion contraption?

The SAA also helped to set in stone the Army’s acceptance of a powerful .45-class handgun cartridge as a baseline. Its long tenure and broad presence across campaigns tied “service pistol” identity to that caliber class well before the 1911 formalized it in semi-automatic form. And while later double-action revolvers and semi-autos would eclipse its rate of fire and reload speed, the Peacemaker era demonstrated something which never goes away: a sidearm that survives field use and stays mechanically simple can outlast more advanced options if the support ecosystem is not ready.

5. Colt & Smith & Wesson M1917 Revolvers (.45 ACP w/ half-moon clips)

The story of the M1917 is the Army doing triage with engineering: when production of the M1911 could not scale to wartime demand, the Army leaned on large-frame revolvers from Colt and Smith & Wesson, adapting them to fire .45 ACP-a rimless cartridge-through the use of half-moon clips to enable its efficient loading and extraction.

That adaptation is the point, since it is an early, high-impact example of interface engineering solving a compatibility problem under pressure of scale. The stopgap was anything but small in number: wartime production ran to 150,000+ revolvers from Colt and 153,000+ from Smith & Wesson. The influence of the M1917 runs into how the Army thinks about “acceptable substitutes” and contingency procurement.

It also proved the service could preserve ammunition commonality even when they were forced into a different operating system-revolver instead of semi-auto-without giving up on the ballistic and supply benefits of a unified cartridge. That mindset-keep the logistics clean, adapt the platform-reappears throughout later small-arms decisions, including how modern programs evaluate modularity and parts commonality. The M1917 revolvers were not supposed to become icons; they became a quiet template for what institutional flexibility looks like when the demand signal spikes and industry cannot instantly comply.

Through all five designs, the thread of consistent engineering is not glamour, but rather survivability in the real world. Each pistol or revolver earned influence by fitting its era’s constraints-industrial capacity, training pipelines, ammunition commonality, and the unromantic reality that maintenance and logistics often decide whether a “good” design stays good in service. Less a parade of famous model names than a record of what the Army repeatedly rewarded: durable mechanisms, manageable recoil and capacity tradeoffs, and procurement choices which could be supported for decades-not just fielded once.”