What will it be like when the AI no longer feels like software, but something that is sharing a room? The promise of automation was not the loudest story at CES 2026. It was the more silent turn towards machines that are to be there companions, pets and little bodied robots that deal with productivity rather than personality.

Others are sold as home managers or general-purpose assistants, however, an increasing portion of the floor tilted in another direction: something which surveys, hearkens, reacts, and clings. The engineering problem is no longer measured in recognition accuracy or success rates in the task. It is concerning the creation of devices that individuals can stand, to have faith in, and to be able to emotionally fit in even when what is inside those devices is unclear as far as the AI is concerned.

1. Phone faces that make a phone a desk companion

The DeskMate by Loona repackages the smartphone and makes it a character: the eyes are huge, the head moves, the body calls are made in the form of a conversation with a person sitting on the table. Such practical tools as Slack integration and meeting assistance are present, yet they are written secondary to the companion layer. Compute is not the most significant spec of the product, but the speed at which the user adopts the device as there, not on.

The latter coincides with adoption studies in which perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use determine emotional reaction, particularly when it comes to embodied devices. In a recent survey study among 452 elderly in China, it was observed that expectations concerning the benefit as well as effort were important sources of emotion in companion-robot acceptance models. Although the target of a desk mate is the office employee, instead of the elderly, the mechanism is not dissimilar: the contact should seem easy enough to be curious enough, and curiosity should become customary.

2. Compromise the robots that follow me, closer

The W1 by Zeroth, which is designed to resemble a real-life WALL-E companion, is characterized by movement and closeness. It is a follower, a carrier of small things, a photographer. The company writes about the high-level mobility and environmental AI, yet the more concrete design proposal is the choice of maintaining the capabilities small and focusing on the physical presence.

That restraint matters. An imitator robot who attempts to do everything will always fail in front of people. A follower robot that moves primarily, evades barriers and remains in the vicinity can offer a more consistent experience- and consistency is what gives an emotional bond the chance to develop around an otherwise restrictively limited device.

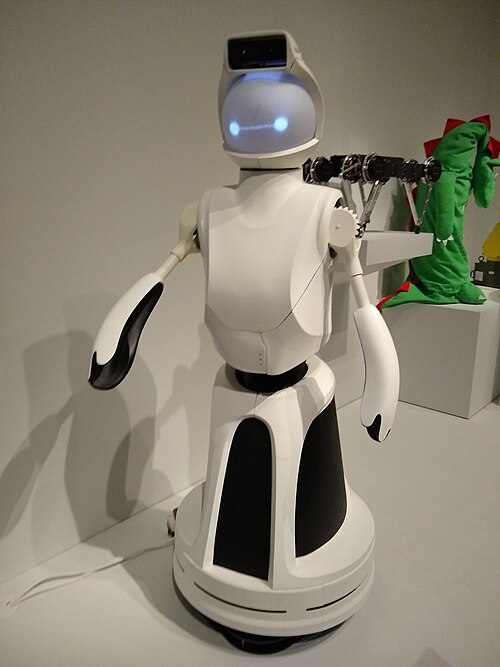

3. Humans in the form of dolls constructed on conversation

Zeroth M1 combines reminders and home-related help with companionship and relies on the Gemini model of Google to talk. The equation is not new to the Asian region; social robots have been sold to children and elderly since decades. CES 2026 was an indication of the rebranding of the Western homes: less robotics showcase, more domestic essence.

Integration is the critical engineering story. Talking is not a good companion, but must be integrated with sensors, scheduling and safety based functions like fall detection. When these components interrelate, the robot ceases to be an innovativeness and begins to act as a domestic system with a personality overlay over it.

4. Robot pets with more touch than talk

Fuzozo is a purring puffball that identifies its owner and responds to being petted thus is an example of a design direction where the experience is delivered by a tactile sensorimotor response. It also has a cellular connection, and the product is no longer a toy that should stay home, but a companion that goes everywhere, with all the durability and battery choices and connection choices it suggests.

The research tailwind of touch-forward design is good. The article Work on robotic pet interventions explains how animal-like robots can enable social and emotional experiences by embodied interaction, particularly in groups. In a research on a commercial robot dog, robotic pets were said to be serious toys that can serve as talking objects as well as play mates in the case of older-adults.

5. Tools used to build companion products by companies now provide emotional companionship products

Ecovacs, which is most famous with robovacs, presented LilMilo: a Bichon Frise type of robot that was pitched as an emotional companion. The company claims that it uses AI and realistic biometrics to identify voices, create a personality, and change it to user habits, but the definition of AI is general. This significant signal is strategic, and not technical: brands related to cleaning and maintenance now consider emotional companionship as a neighbor to robotics at home.

This transition alters the way customers weigh-up values. Rather than seeking the duration a given machine will save you, the purchaser is emboldened to pose on an attachment, routine, and whether the gadget will leave a space with less to occupy. It is not an ROI calculation of having a vacuum cleaning the house.

6. Robot companions that scale due to the need to have them in care systems

Beyond the trade shows of consumers, companion robotics has been influenced by the aging societies and care gaps. Hyodol, a doll-like companion robot that is sold in South Korea through public programs, combines reminders and alerts with emotional engagement and surveillance. By November 2025, more than 12,000 Hyodol robots were already sold to older adults living alone, and more have been purchased directly by families.

The design decisions made at Hyodol could be interpreted as a product-playbook of acceptance: comfortable, cuddling shape, use of simple touch interactions, and a voice that is unthreatening and welcoming. The product also demonstrates the limits of companion tech, its own CEO, Jihee Kim, acknowledges that it must be treated as an aid and not a substitute to human care, and more independent seniors find it to be noisy and annoying.

7. The trust problem created by vague “AI” claims

Across the category, many products market “AI” without explaining how models, sensors, and data flows actually operate. That ambiguity matters because companion devices are, by definition, intimate: they sit in bedrooms, kitchens, and living rooms, and they often rely on microphones, cameras, and identity recognition to feel personalized. Adoption research repeatedly flags perceived risk as a brake on acceptance. In the same China-based acceptance study, familiarity was a significant negative predictor of perceived risk, suggesting that clarity, onboarding, and repeated exposure can reduce anxiety.

For consumer companion robots, that translates into a practical requirement: the product must communicate what it collects, what it stores, and what it does locally versus in the cloud, in language that matches the audience’s comfort level. Robot pets and companions are no longer a sideshow to “real” home automation. They are an emerging layer of physical computing where the primary output is not a task completed, but a relationship maintained. As more AI moves into bodiesrolling, blinking, purring, and following engineering success becomes inseparable from human factors: frictionless setup, predictable behavior, and designs that earn trust without demanding constant attention.