“It took just 30 feet of altitude and a catastrophic structural failure to bring the U.S. MD‑11 fleet to a standstill. On November 4, UPS Flight 2976, a 34‑year‑old MD‑11F bound for Honolulu, lost its left engine and pylon seconds after rotation from Louisville’s Muhammad Ali International Airport. The engine assembly arced over the wing in a fireball, debris rained across an industrial zone, and the trijet slammed into nearby buildings, killing all three crew and 11 people on the ground. Within days, the FAA issued an emergency grounding of every MD‑11 and MD‑11F worldwide, later extending the order to certain DC‑10s sharing the same pylon architecture.

1. Forensics of a Pylon Failure

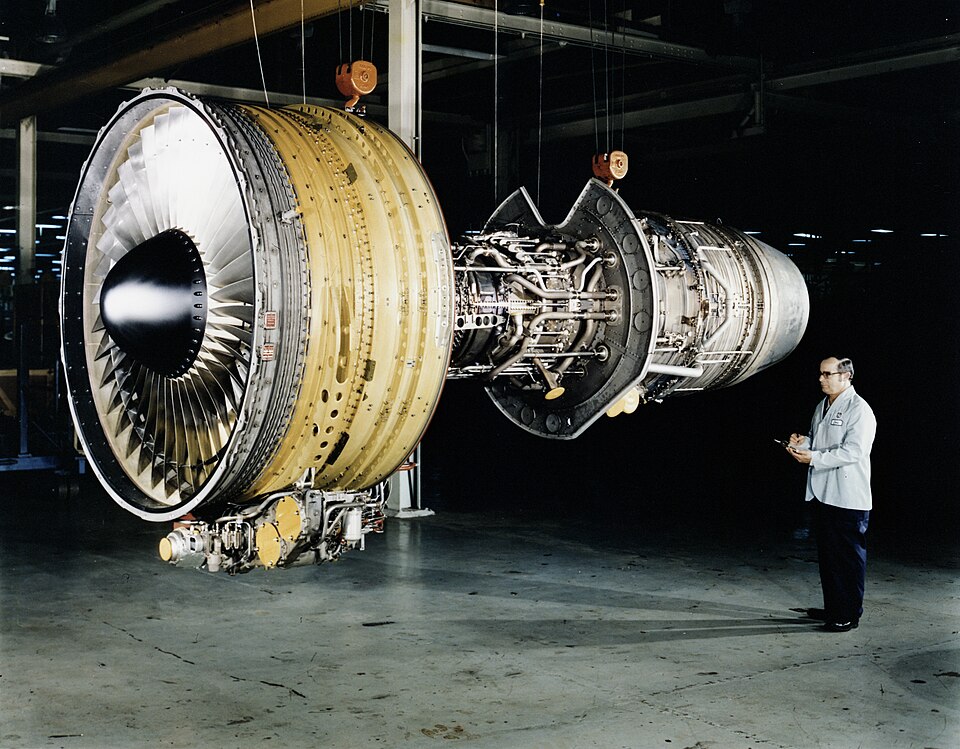

The National Transportation Safety Board’s preliminary findings focus on fatigue cracks in the aft mount lugs of the left engine pylon. These lugs, together with a spherical bearing, constitute the structural interface between the pylon and the wing clevis. Metallurgical analysis disclosed progressive cracking around the lug bores combined with overstress failure when the part finally let go. The MD‑11’s GE CF6‑80C2 engines each produce more than 52,000 lb. of thrust at takeoff, and when the aft mount broke, the engine pivoted on the forward mount before tearing away. Investigators noted the similarities to the 1979 DC‑10 crash of American Airlines Flight 191, although that accident resulted from improper maintenance, not age‑related fatigue.

2. Engineering Heritage and Known Weak Points

The MD‑11’s pylon design descends directly from the DC‑10, a configuration that has come under scrutiny since that aircraft’s notorious Flight 191 disaster. Although the MD‑11’s mounts were strengthened, the basic load paths remain similar. Over decades of service, cyclic loads, thermal expansion and vibration can initiate microscopic cracks at high‑stress points such as the lug bore fillets. Without sophisticated non‑destructive inspection-ultrasound, eddy current or immersion methods such cracks may not be detectable during routine visual checks. The accident aircraft had accumulated 92,992 hours and 21,043 cycles, and some Special Detailed Inspections called for by the current maintenance programme were not yet due.

3. The Immediate Operational Shock

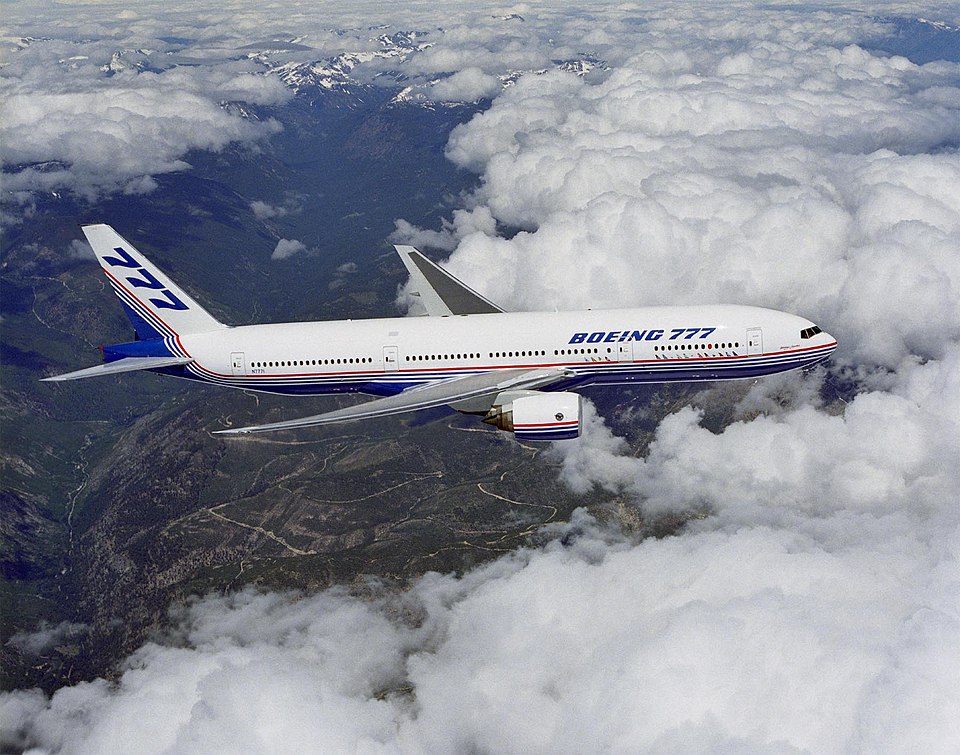

UPS and FedEx operated a combined total of just over 50 MD‑11s prior to the grounding. That is a small percentage of their fleets, but these trijets fly long‑haul trunk routes where payload and range matter. UPS has shifted lift to 747‑8Fs and 767‑300Fs, supplemented by ACMI leases from carriers like Cargojet and Amerijet. FedEx is redeploying 777Fs and 767Fs, chartering supplemental capacity, and consolidating schedules. Network planners are working to balance aircraft, crews, and slots to protect service levels, but analysts expect reduced flexibility and upward pressure on seasonal rates.

4. Western Global’s existential threat

The grounding is a direct hit to the survival of Western Global Airlines. Of its 19 aircraft, 15 are MD‑11Fs averaging more than 30 years in age. An internal memo from VP of HR Tom Romnios called the situation “devastating” and “untenable,” confirming indefinite furloughs for MD‑11 pilots. The carrier had hoped to return quickly via non‑invasive inspections, but Boeing advised that “highly invasive” work, repairs, and part replacements would be required. No timeline was given, leaving Western Global’s thin‑margin ACMI model severely strained.

5. Economics of an Aging Widebody

The principal attractions of the MD‑11 in cargo service are its low acquisition cost, 200,000‑lb‑plus payload and intercontinental range. But with production ended since 2000 and the youngest frames now 25 years old, operators face escalating maintenance costs and fuel burn penalties relative to modern twins. The FAA’s directive presents a stark choice: invest millions per airframe in structural remediation, or accelerate retirement. Carriers were already weighing phase‑outs in favor of 777Fs, 767Fs and converted A330Fs even before the crash.

6. ETOPS and the End of the Trijet

The MD‑11 was conceived when three engines offered a performance and range advantage over twins restricted by early ETOPS rules. Advances in engine reliability and the expansion of ETOPS to 330 minutes erased that advantage, leaving the third engine an economic liability. Modern twins like the 777F and forthcoming 777‑8F offer superior fuel efficiency, lower maintenance, and higher dispatch reliability, sealing the trijet’s fate in mainstream cargo operations.

7. Technical Path to Return or Retirement

Boeing is working on inspection and repair protocols for FAA approval, but the industry sources say these will not be ready before 2026. The work will likely entail removing the pylon, non-destructive testing of lug bores, possible replacement of lugs and spherical bearings, and then reinstallation with new hardware. Such invasive procedures require considerable downtime and capital, challenging the business case for aging freighters with limited remaining cycles.

8. Fleet Replacement Strategies

Operators are considering interim lift from stored 747‑400Fs, 767‑300ER P2Fs, and A330‑300P2Fs as a stopgap while MD‑11 capacity is offline. In the longer term, Boeing’s 777‑8F will anchor the heavy segment, with a possible 787F filling the mid‑size role. Conversion programs for the 787 face composite‑structure challenges but promise 20–25% fuel‑burn savings over legacy metal freighters.

The transition requires overlapping fleets, crew cross‑qualification, and retooled maintenance pipelines to avoid capacity gaps. The Louisville crash compressed what might have otherwise been a gradual MD‑11 sunset into an abrupt, open‑ended grounding. Whether a handful return to niche roles or the type exits U.S. skies entirely, the accident underlines the engineering, economic, and operational pressures that finally caught up with the last of the trijets.”