The question lingers in every control room and every regulator’s office: How did a vessel designed for the world’s most ambitious deep-sea civilian tourism project implode so catastrophically and why were so many warning signs disregarded? The US Coast Guard’s final report on the OceanGate Titan disaster delivers a chastening, minute-by-minute analysis of engineering failures, regulatory loopholes, and a culture more concerned with innovation and urgency than safety, lessons that resonate right across the submersible industry.

1. A Preventable Tragedy: The Coast Guard’s Findings

The Coast Guard’s 335-page report concluded with the finding, “This marine casualty and the loss of five lives was preventable,” said Jason Neubauer, chairman of the Marine Board of Investigation. The investigation determines that there was a series of failures technical, managerial, and regulatory that led the Titan to collapse on June 18, 2023. OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush is at the core of the findings, as he “had full control over every aspect of the company’s operations and engineering decisions.” His placing safety last and autocratic style of leadership created a culture in which the Titan’s eventual downfall became all but inevitable the report concluded.

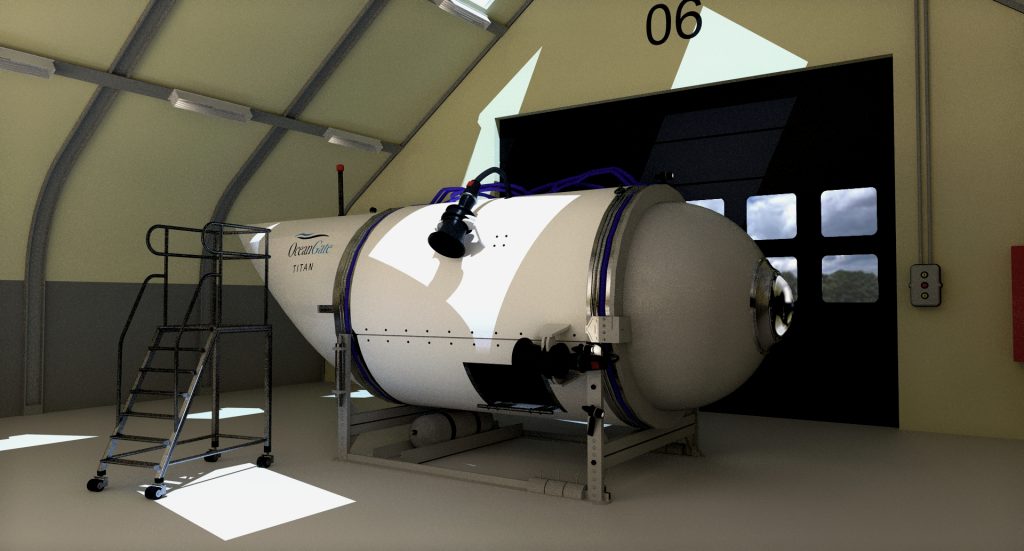

2. Carbon Fiber Hull: Promise and Peril

The Titan’s hull was constructed from carbon fiber composite, material lauded for its strength-to-weight ratio and resistance to corrosion. But as recent research emphasizes, “composite pressure hulls will have more complex damage mechanisms than the traditional metal counterparts” deep-sea composite review. Unlike steel or titanium, failure modes of carbon fiber delamination, matrix cracking, and brittle fracture are difficult to predict and typically fatal. The Coast Guard report summarizes that Titan’s hull “showed evidence of fatigue and delamation under testing before the fatal dive,” and that all four one-third-scale replicas exploded under pressure testing. Defying these warning signs, OceanGate proceeded with manned flights, an action that led to their deaths.

3. Shortcomings in Design and Fabrication

The report outlines several engineering faults. More importantly, the forward dome a pressure-carrying component of critical importance was called out for 18 securing bolts but only functioned with four under dive conditions. When all four bolts sheared away on a 2021 dive, the dome broke away in a near-catastrophic failure. Also, adhesive welds that connect the carbon fiber hull to titanium endcaps were recognized as a vulnerable area as early as 2013, but OceanGate did not conduct the recommended study into how well they held up under deep-sea pressure report data. The Coast Guard found that “the adhesive used to connect the carbon fiber hull to the titanium parts had pulled away from the entire forward section.”

4. Maintenance, Storage, and Operational Neglect

Financial limitations exacerbated safety risks. The Titan was stored outside in a Canadian parking lot for seven months, exposed to freeze-thaw cycles and rain situations that would have weakened the structural integrity of the hull. The report describes a “persistent pattern of sacrificing safety and operational integrity for financial savings,” including contractor reliance, vacant engineering slots, and a lack of strict maintenance procedures maintenance findings.

5. Regulatory Gray Zones and Certification Failures

Maybe of greatest concern to regulators, Titan operated in a regulatory vacuum. The vessel was not registered, certified, or inspected by any approved authority. OceanGate circumvented small passenger ship regulations and regulation in general by redefining passengers as “mission specialists.” The company’s own public testimony waved aside third-party certification as unnecessary, claiming it would hinder innovation regulatory analysis. As Sal Mercogliano, maritime historian, clarified, “Submersibles don’t fall under international law like oceangoing ships do. They’re in a very gray area.” The Coast Guard report calls for “new legislation to extend U.S. oversight authority over deep-sea commercial submersibles with American citizens onboard.”

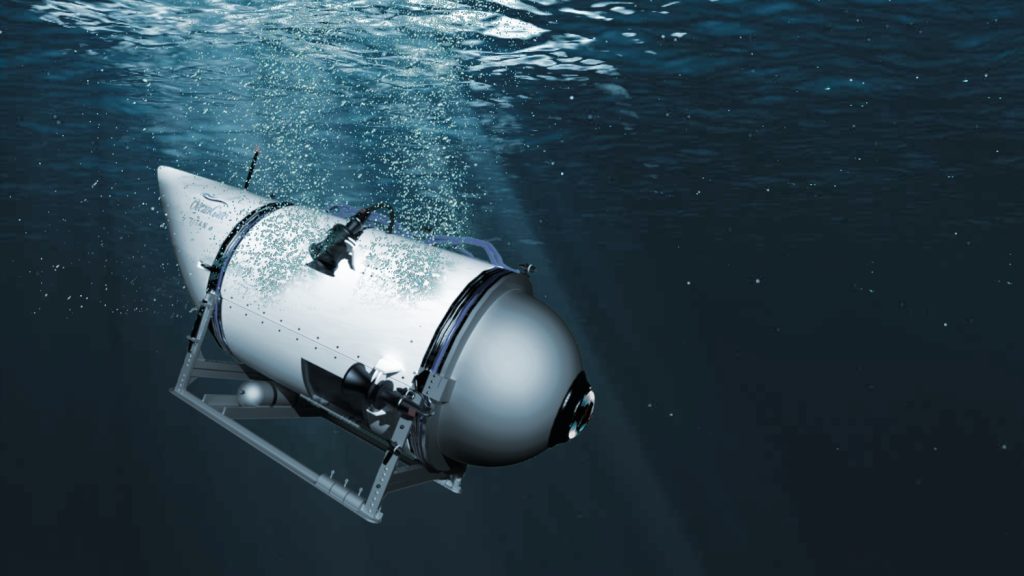

6. Implosion Physics: Catastrophic Failure Mechanisms

The Titan’s final plunge ended in a instant implosion on the ocean floor at 3,346 meters, exposing the occupants to 4,930 pounds per square inch of water pressure. According to the report, there was a “loss of structural integrity of the Titan pressure vessel,” likely due to a defect in carbon fiber or adhesive joint. Composite hull implosions highlight that “buckling can result from the built-in anisotropy and heterogeneity of composite materials,” and that “material failure–initiated implosions are more challenging to predict than buckling-initiated implosions” composite implosion review. Composites do not, by default, provide warning signals such as metallic hulls and may be complete and abrupt failures.

7. Toxic Culture and Suppression of Dissent

The Coast Guard investigation found that dissent was punished at OceanGate and safety concerns were actively suppressed, and there was a “toxic workplace environment.” Former employees gave testimony that raising concerns about something as fundamental as the integrity of the hull or cost-cutting was grounds for termination or threat of a lawsuit. “The combined result was a culture of authoritarianism and toxicity where safety was not only deprioritized but actively repressed,” the report said. This environment, coupled with scant external regulation, set the stage for disaster.

8. Industry and Regulatory Lessons

The Coast Guard proposals are ambitious: third-party mandatory certification, state-of-the-art communication systems, and uniform regulation on all submersibles. The report asks regulators to “extend federal and international standards to all submersibles and mandate all submersible operators to provide dive and emergency response plans to the local Coast Guard.” For deep-sea workers, the tragedy of the Titan is a painful reminder that safety must never be overtaken by innovation. As one of the ex-OceanGate engineers explained, “I knew that hull would fail. It’s an absolute mess.”

The Titan disaster has been a force for regulatory change, with family members of the victims and industry executives calling for a new generation of accountability. The hope, one that the Dawood family also hopes for, is that “this incident serves as a turning point and one that drives meaningful reform, rigorous safety standards, and effective oversight within the submersible industry.”