The U.S. Coast Guard’s last report on the 2023 Titan submersible disaster starts with a severe judgment: “This marine casualty and loss of five lives was preventable.” For maritime engineers, safety officials, and investigative journalists, the lessons in the 335-page report are a warning and a call to action.

The Titan’s devastating implosion was not an isolated accident, but the product of systemic failures in engineering, regulatory avoidance, and a poisonous safety culture that pervaded OceanGate operations.

1. Intimidation and Regulatory Evasion

OceanGate’s strategy for regulation was characterized by what the Coast Guard referred to as “intimidation tactics” and calculated manipulation. The company “used intimidation tactics, allowances for scientific operations, and the company’s positive reputation to avoid regulatory attention,” the report concluded. This included exploiting regulatory loopholes and selling paying customers as “mission specialists” to get around commercial passenger ship regulations. OceanGate managers, including CEO Stockton Rush, bullied safety-oriented staff into submission through firing or lawsuits, creating a chilling effect that silenced dissent. As a former marine operations director said, during his testimony, “the message was clear: Either he or I had to go.” Then he came to me and said, ‘It’s not going to be me’.

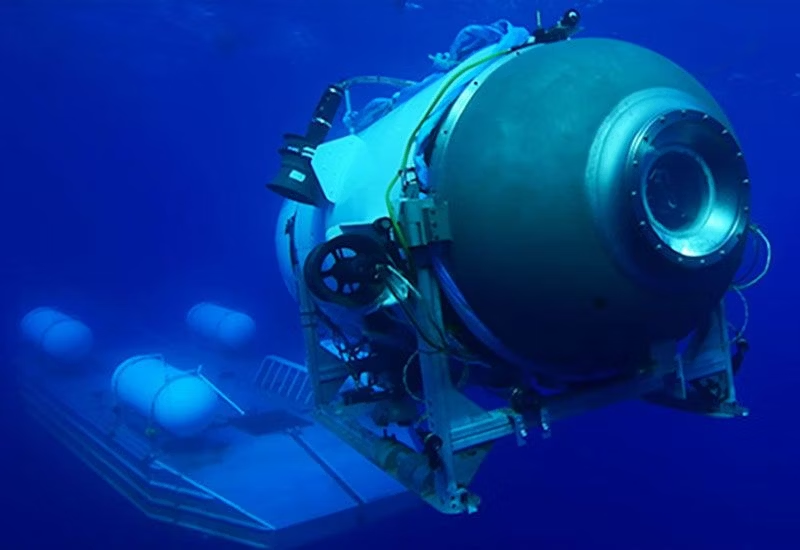

2. Engineering Design and Testing Failures

Titan’s design procedure also did not adhere to standard deep-sea submersible engineering rules. Unlike industry-practice pressure hulls made out of titanium or steel, OceanGate utilized a carbon fiber composite hull for weight and cost savings. Carbon fiber was never tested for multiple deep-ocean cycles at ultra-high pressures, though. Rob McCallum, a specialist in deep-sea operations, spoke of: “When you listen to the sounds of that hull under pressure, and the cracking and popping, that’s the sign of damage in the hull, that means the hull is weakening. It is an actuarial certainty that it will fail”. OceanGate’s design and testing procedures did not include in-depth lifecycle analysis, finite element simulation, or full-scale destructive testing as required by accepted classification societies.

3. Neglect of Hull Damage and Maintenance Practices

The Titan submersible had a series of accidents on the way to the fatal dive, such as a 2019 four-foot longitudinal hull crack and in 2022 got stuck on the Titanic wreckage that resulted in a huge bang later diagnosed as a “substantial delamination” of the hull. Each time, OceanGate’s response was superficial. Instead of conducting third-party inspections or non-destructive testing, the company “over-relied on its real-time monitoring system” and was returned to service after superficial visual inspections. The Coast Guard report concluded, “The failure to adequately analyze post-surfacing data. is a serious oversight, due to negligence”.

4. Toxic Safety Culture and Whistleblower Suppression

OceanGate’s corporate culture was described as “toxic and authoritarian,” where safety was “not just deprioritized but actively suppressed.” Employees and contractors who raised warning flags were fired or threatened. Having previously served as director of marine operations, David Lochridge testified, “I knew that hull would fail. It’s an absolute mess.” Lochridge was fired for reporting safety issues in 2018 and then sued by OceanGate for breaking confidentiality. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) never replied to his whistleblower complaint, a shortfall the Coast Guard now acknowledges might have made the disaster possible.

5. Economic Pressures and Operational Cuts

OceanGate was deep in financial distress by 2023, forcing employees to forego pay and increasingly depending on contractors who had minimal submersible experience. The Titan remained outside in Canada for seven months, exposed to cycles of freezing and thawing and rain, which presumably accelerated hull degradation. Routine maintenance and engineering crewman jobs were unfilled, and cost-saving measures meant that text messages, not the industry standard voice systems, were used. “OceanGate’s penny-pinching, contractor use, and money management failures left the company not ready to handle the risks and complexities of deep-sea exploration,” the Marine Board of Investigation said.

6. Departure from Industry Standards and Regulatory Shortfalls

OceanGate operated Titan “completely outside the accepted deep-sea procedures,” skipping third-party classification and certification. The company’s manual included only four pages of dive safety procedures, a “serious shortfall for a company with manned deep-sea submersible operations.” A lack of domestic and international regulatory systems for experimental submersibles was cited as one reason. The Coast Guard then recommended increasing regulation and uniformly establishing standards for all submersibles, both in domestic waters and overseas waters, and the status of passengers.

7. Submersible Industry Lessons

The Titan tragedy has ignited calls for a sea change in submersible safety. The Dawood family, who lost two members in the tragedy, stated, “If Shahzada and Suleman’s memory can be an impetus for regulatory reform that will ensure such a loss never happens again, it will bring us some measure of peace.” Suggestions by the Coast Guard include third-party certification as a requirement, expanded requirements on communication, and strict documentation of emergency response plans and dive.

Industry commentators point out that deep-sea vessels must be designed, built, and operated to strict engineering and safety principles, under strict engineering and safety regulations, and strict regulatory oversight. The OceanGate technical failures and cultural shortcomings are a sobering reminder: in the unforgiving environment of the deep ocean, there is no substitute for engineering professionalism, transparency, and accountability.