Could the most colorful ecosystems on the planet be living in constant darkness, under pressure that would crush a submarine? Recent findings in the northwest Pacific’s hadal trenches indicate the answer is a resounding yes, as scientists find thriving populations of tubeworms and mollusks at depths greater than 31,000 feet well beyond sunlight and traditional life.

1. Full-Ocean-Depth Exploration: Engineering at the Abyss

The travel to such abyssal environments involved the use of sophisticated submersibles that could operate at pressures over 1,000 atmospheres. The Chinese team made use of the manned submersible Fendouzhe, built with full-ocean-depth capability, to comprehensively survey the Kuril–Kamchatka and Aleutian trenches. Equipped with hydraulically operated manipulators, high-definition video, and accurate conductivity–temperature–depth (CTD) sensors, the vehicle allowed for in situ sampling and direct observation of biota and geochemistry on the trench floor along a 2,500 km segment of the hadal zone.

2. Finding Chemosynthetic Oases

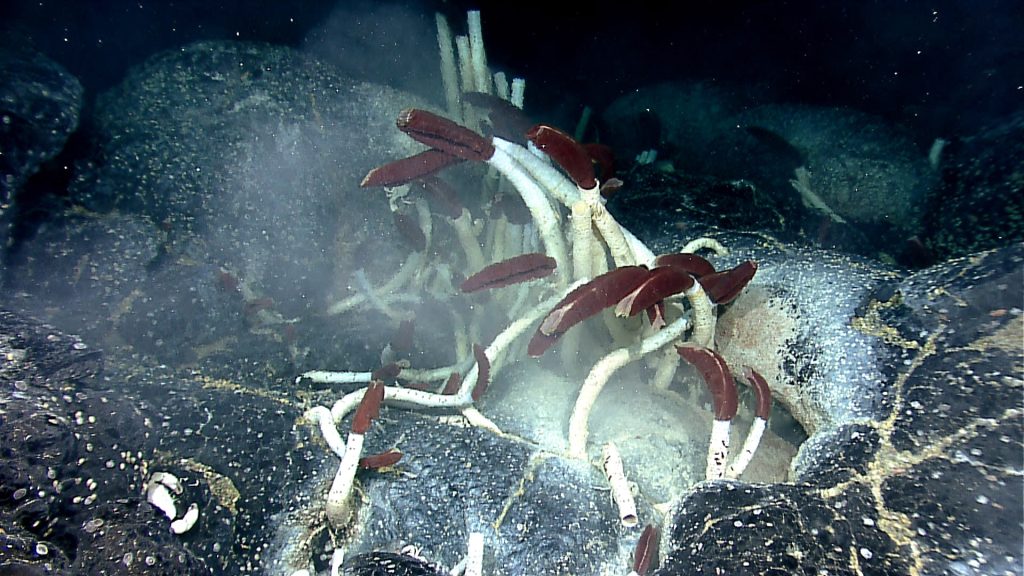

The cameras of the submersible caught dense congregations of frenulate siboglinid tubeworms and bivalve mollusks, which constituted the deepest and most widespread chemosynthesis-based communities that had ever been recorded. At places like “The Deepest,” which had a depth of 9,533 meters, colonies of Polybrachia and Lamellisabella tubeworms covered the sediment, with their tubes protruding from methane-rich muds. Tube-dwelling polychaetes, gastropods, crinoids, holothurians, and amphipods formed associated fauna that created a sophisticated ecosystem structure. In the Aleutian Trench, bivalve-rich fields some two kilometers long nourished equally diverse communities, with densities of more than 5,800 Siboglinidae and almost 300 Bivalvia per square meter.

3. Microbial Chemosynthesis: The Motor of Life in the Dark

Life is severed from photosynthesis in these dark depths. Microbial communities, instead, utilize chemical energy derived from methane and hydrogen sulfide migrating along tectonic faults. As explained by Ricci and Greening, “Chemosynthesis fixes carbon using energy acquired from reduced chemical compounds and is a primordial process that occurs ubiquitously throughout contemporary marine ecosystems.” Within the hadal trenches, the process is not an edge effect but the dominant driver of ecosystem productivity. Methane is produced microbially from sedimentary organic matter, subsequently oxidized by archaea and bacteria to produce the nutritional foundation for tubeworms and bivalves frequently through symbiotic associations.

4. Symbiosis and Biochemical Adaptations

The survival of the tubeworms and bivalves is a result of complex symbioses with chemosynthetic bacteria. Genomic surveys of close relatives, such as Riftia pachyptila, indicate gene family expansions associated with sulfur metabolism, detoxification, antioxidative stress, and oxygen transport. The trophosome, a specialized organ of tubeworms, contains dense assemblages of endosymbionts that metabolize sulfide and methane and fix inorganic carbon into organic compounds. “The trophosome is a multifunctional organ characterized by intracellular digestion of the endosymbionts, excretory product storage, and hematopoietic activity,” writes André Luiz de Oliveira. Such adaptations are necessary to survive in high-pressure, low-oxygen, and chemically dynamic settings.

5. Physiological Limits and Polyextremophily

Hadaltrench fauna are authentic polyextremophiles, withstanding pressures over 1,000 bar, subfreezing temperatures, and extremely high chemical gradients. Microbial and metazoan mechanisms involve alterations in membrane fluidity, enzyme shape, and metabolic pathways to preserve cellular functions under high pressure and subfreezing temperature.

As synthesized by Merino et al., “Microorganisms have been found in a wide range of extreme environments, essentially in any place where liquid water for use by life is present.” The presence of hyperpiezophilic bacteria and barophilic archaea in such sediments highlights the adaptability of life at the margins.

6. Geological Drivers and Carbon Cycling

The Aleutian and Kuril–Kamchatka trenches are tectonically active, and faulting caused by subduction generates conduits for seepage of methane and hydrogen sulfide. Geochemical sampling of sediment cores showed anomalously high methane levels and indications of gas hydrate formation. Microbial CO₂ reduction to methane in these sediments supports local biota as well as contributes to global carbon cycling. “The ubiquitous methane-rich settings in two hadal trenches, where microbial reduction of CO₂ from sedimentary organic matter is likely to lead to methane production, indicate a dynamic and thriving microbial community within the hadal sediments,” the researchers said.

7. Wider Implications for Deep-Sea Ecology and Astrobiology

The discovery contradicts the old paradigm that deep-sea life is largely supported by detritus raining down from the surface. The prevalence of chemosynthesis-based communities at extreme depth indicates that chemical energy could be a limiting factor that determines hadal ecosystems. This new discovery has significant implications for biogeographical connectivity between trench systems and the possibility of life on extraterrestrial ocean worlds. As noted by the research team, “These findings challenge current models of life at extreme limits and carbon cycling in the deep ocean.”

The continued exploration of these deep habitats, facilitated by the progress in submersible technology and molecular biology, continues to widen the known limits of life on Earth and informs the quest for life in the universe.