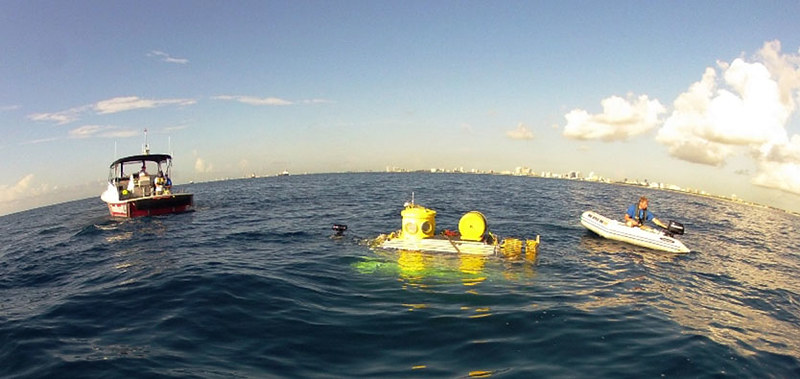

Was the Titan tragedy inevitable, or was a culture of irresponsible engineering and poisonous leadership predestined to destroy OceanGate’s flagship before it ever made contact with the Atlantic? The last report from the US Coast Guard, which takes more than 300 pages to tell its tale, pulls no punches in its criticism: “This marine casualty and the loss of five lives was preventable,” declared Jason Neubauer, the Marine Board of Investigation chair. The June 2023 implosion of the Titan submersible was no accident, but a consequence of a chain of technical, organizational, and ethical breakdowns that provide a salutary lesson for marine engineers and safety professionals.

1. Toxic Leadership and Degradation of Safety Culture

The findings of the Coast Guard lay the blame squarely at the feet of OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush, whose leadership style is described as “dangerous and deeply unpleasant.” The report documents a workplace where “intimidation tactics, allowances for scientific operations, and the company’s favorable reputation” were leveraged to evade regulatory scrutiny.

Staff members who had questioned safety issues were consistently threatened with dismissal or lawsuits, the atmosphere being such that “the dismissal of safety concerns by experienced operators is highly abnormal and unacceptable in the submersible industry” as opined by the director of marine operations. This poisonous culture muzzled internal opposition and left important engineering choices unmonitored.

2. Cutting Corners in Engineering and Overlooked Inspections

Titan’s operational history is a laundry list of close calls and disregarded warnings. The Coast Guard report summarizes that the sub was “undocumented, unregistered, non-certificated, and unclassed,” and Rush kept dodging important inspections and data analyses. In one infamous instance, Rush ordered the astronauts to use a mere four bolts to hold the 3,500-pound dome in place intended for eighteen since “it took less time.” When the bolts sheared away during a lifting maneuver, the dome came crashing down onto the launch platform, an event typical of the havoc caused by wider disregard for engineering best practices. The report further describes a 2019 occurrence when a pilot found a crack that ran four feet along the carbon fiber body; instead of shutting down, Rush “intended to grind it out, fix it, and rebuild the sub in three weeks, then dive it again” as told by the engineering director.

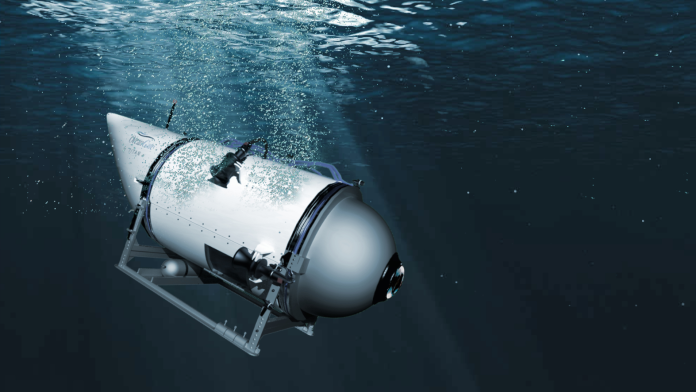

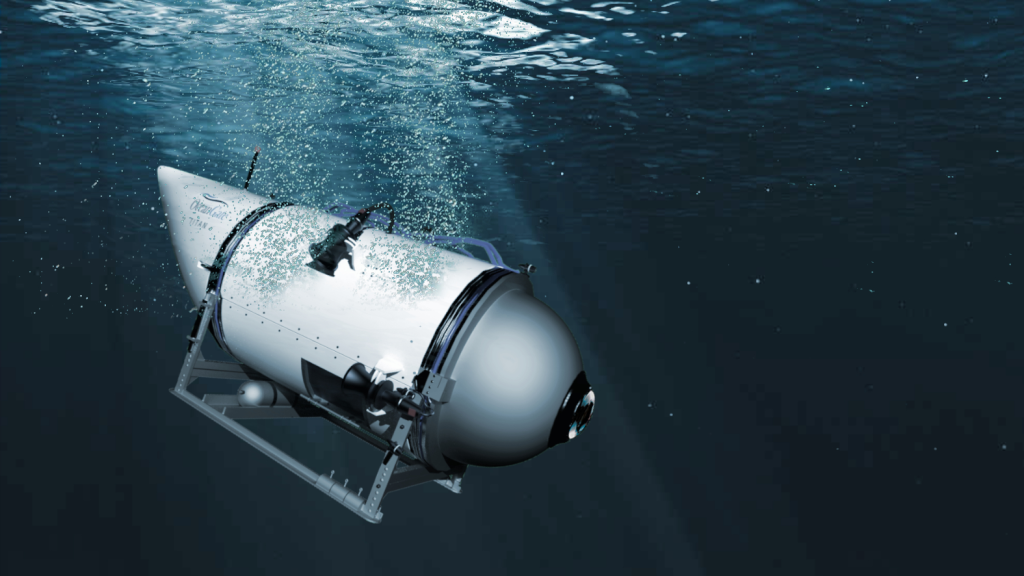

3. The Mechanics of Catastrophic Implosion

The Titan’s hull, made from carbon fiber a composite material never before employed on deep-diving submersibles gave way to the tremendous pressures of the North Atlantic at a depth of about 3,800 meters. At this depth, the outside pressure approaches almost 5,000 psi, the equivalent of the Eiffel Tower crushing down upon the vessel. When the hull did fail, it collapsed inwards at around 1,500 mph, or 2,200 feet per second, with the full collapse happening in around one millisecond. As is often explained by former US nuclear submarine man Dave Corley, “The time involved in total collapse is approximately one millisecond, or one thousandth of a second. A human brain reacts instinctively to a stimulus in around 25 milliseconds.” The implosion had been so violent that the internal air of the autos auto-ignited, immediately burning the occupants to ash as per expert opinion.

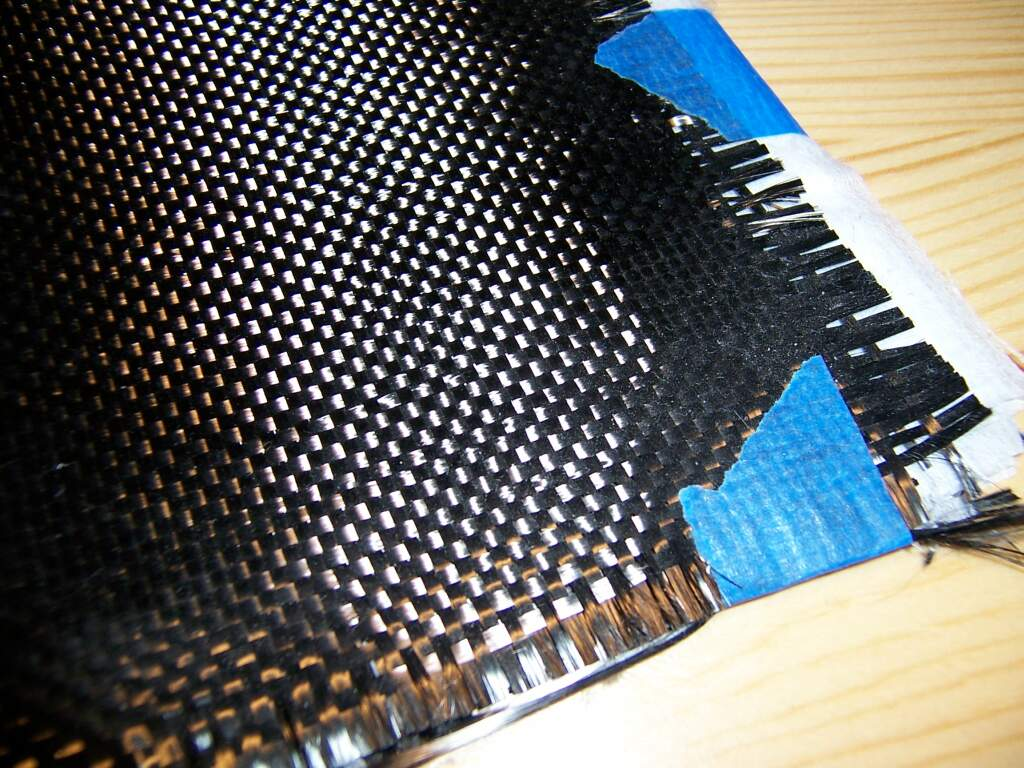

4. Defective Materials and Untested Design Options

Carbon fiber’s unpredictable performance under cyclic loading and deep-sea pressure was widely known in the world of engineering. Rob McCallum, a specialist in deep water operations, warned, “When you listen to the sounds of that hull under stress, and the cracking and the popping, that’s the sign of damage in the hull, that means the hull is getting weaker… It is a mathematical certainty that it will fail.” Yet OceanGate pressed on, even after the hull suffered “irreversible” damage during a 2022 entanglement with the Titanic wreck. The firm’s excessive dependence on systems that report in real time without serious analysis of the data resulted in red flags being consistently disregarded as the Coast Guard report states.

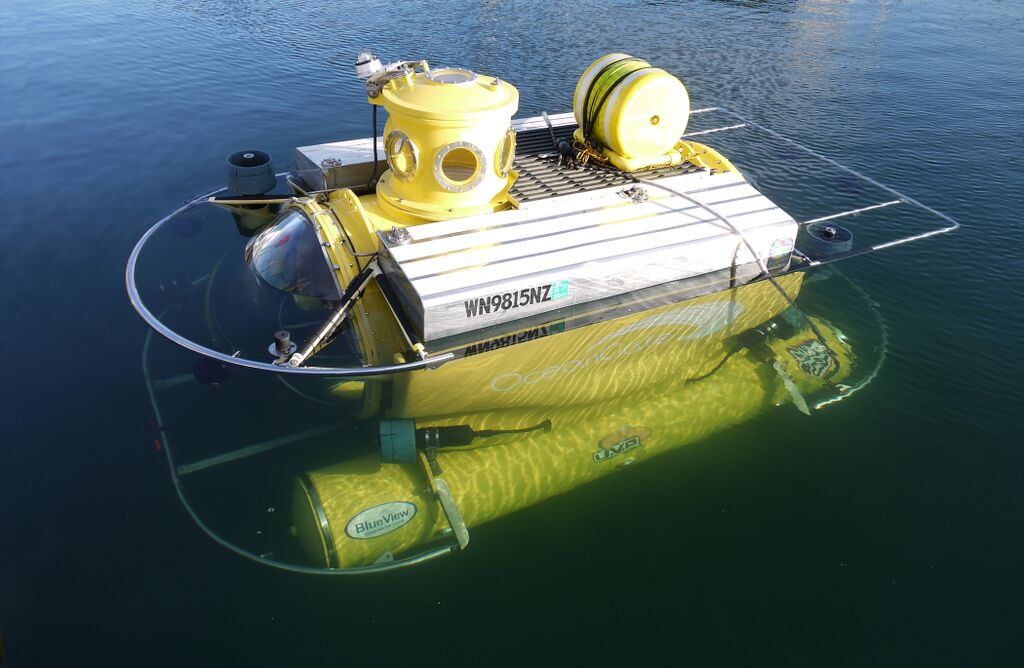

5. Regulatory Avoidance and Lack of Classification

OceanGate’s tactic of avoiding regulation was intentional and comprehensive. The firm recategorized paying customers as “mission specialists” to avoid regulations on small passenger boats, and designated its subs as oceanographic research vessels. This enabled the Titan to work “well beyond the established deep-sea protocols that had heretofore helped to provide a strong safety record for commercial submersibles.” The report points out that “there is a need for more robust oversight and clear alternatives for operators who are venturing beyond the current regulatory framework” as stated by Neubauer. In contrast to submersibles classified by DNV or ABS, the Titan was never exposed to third-party classification, and its structural soundness remained untested.

6. Cost Reductions and Exposure to the Environment

Financial constraints in 2023 caused OceanGate to leave the Titan outside in a Canadian parking lot for seven months, subjecting the hull to temperatures between 84.2°F and 1.4°F, snow, sleet, and several freeze-thaw cycles. The Coast Guard determined that “this exposure could have damaged the carbon fiber hull,” weakening its structure prior to the final, lethal dive. Cost-cutting attempts at storage and use of unqualified contractors further compromised operations safety. “OceanGate’s poor financial management, overreliance on contractors, and emphasis on cost savings over safety left the company unprepared to deal with the intricacies and danger of deep-sea exploration,” the report says as detailed in the MBI findings.

7. The Broader Lessons for High-Risk Engineering

The Titan disaster highlights the imperative necessity of having a strong safety culture in high-risk engineering projects. As comparative studies of safety management have pointed out, good organizations create settings where “leadership commitment, effective communication, continuous training, and the integration of ergonomic and human-centered design principles” are absolutely essential as per recent research on safety culture. The OceanGate case illustrates how the failure of these principles coupled with unbridled authority and cost-saving decision-making may result in tragic consequences.

The Titan’s collapse is a harsh reminder that in the deep sea, as in all high-risk environments, engineering discipline and safety culture are not choices only they stand between innovation and catastrophe.