A rhetorical question: What goes wrong when deep-sea innovation meets a lack of respect for engineering principles and a poisonous corporate culture? The explosion of OceanGate’s Titan submersible, laid bare in the U.S. Coast Guard’s thorough inquiry, provides a chilling response one that resonates across the engineering and maritime safety sectors.

1. Intimidation and Regulatory Evasion

The Coast Guard’s 335-page report exposes a pattern of “intimidation tactics” and regulation-evading conduct that enabled OceanGate to fly the Titan submersible outside of established deep-sea protocols. Investigators concluded, “For a number of years leading up to the accident, OceanGate used intimidation strategies, concessions for scientific missions and the company’s good name to avoid regulatory oversight.” Through exploiting regulatory loopholes and causing ambiguity, OceanGate was able to avoid oversight that is typical in the submersible industry. This lack of external checks allowed for a culture in which dissent was not allowed and safety was regularly sacrificed. The report points out that the company leadership “used dismissals of high-level employees and the threat of being dismissed to discourage workers and contractors from raising safety issues” OceanGate did not adhere to standard engineering procedures for safety, testing, and maintenance.

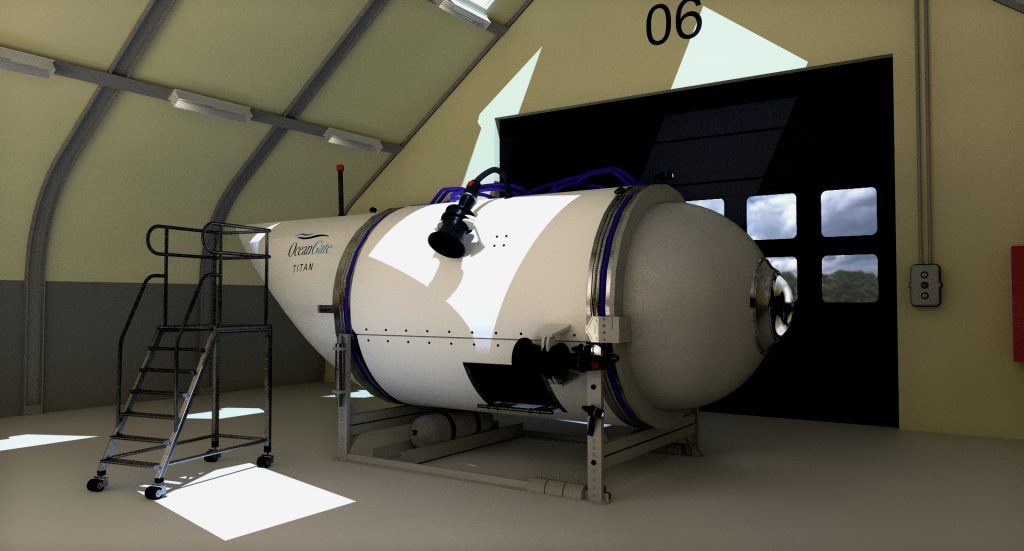

2. Design and Testing: A Deviation from Engineering Principles

OceanGate’s design and testing process of the Titan radically departed from industry standards. The Coast Guard determined that the “design and testing procedures for TITAN failed to properly address many of the basic engineering principles that would be important in ensuring safety and reliability in such a inherently dangerous environment.” Rather than presenting the vessel for third-party certification standard procedure for responsible submersible operators CEO Stockton Rush claimed that such regulation would “stifle innovation.” The company’s proprietary “Risk Index” was irregularly used and never resulted in a dive being canceled, even though there were documented anomalies no dives were ever cancelled on account of RTM system alerts. The lack of a separate safety officer further undermined responsibility, with workers looking to non-management employees such as Rush as the de facto decision-maker on safety.

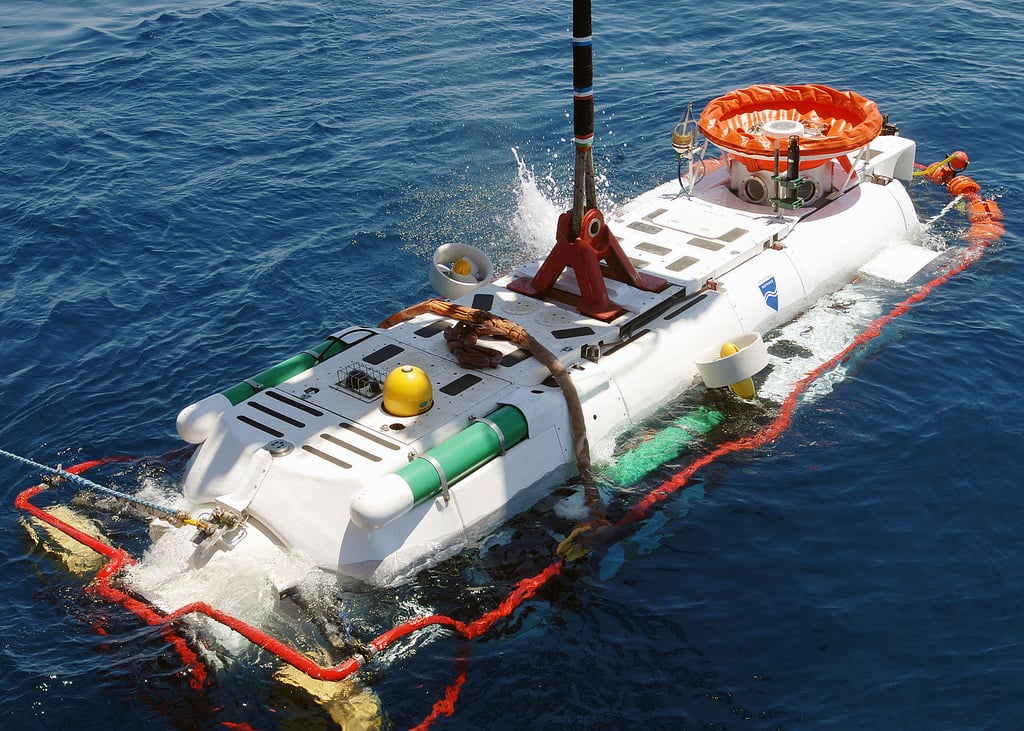

3. The Carbon Fiber Hull: An Unproven Material for Deep-Sea Pressure

At the center of the Titan’s failure was its carbon fiber hull, a material selection based on cost and transportation issues more than deep-sea performance. Although carbon fiber provides high specific stiffness and strength, its compression behavior, particularly in the context of thick-walled structures, is still complicated and less metallic in nature. The Coast Guard attributed the implosion to “loss of structural integrity” in the carbon fiber hull, citing that “the material was not recommended for deep-sea exploration.” Investigation in composite pressure hulls emphasizes the necessity of strict inspection and testing because of intricate failure modes like delamination, snap buckling, and material fatigue structural failure problem of composite pressure hulls has drawn much attention. The Titan’s vessel had already taken damage in several incidents, such as a bang that was caused by delamination, but was still operated without full inspection.

4. Defective Safety Culture and Silencing Whistleblowers

The Coast Guard report is categorical: “OceanGate’s toxic safety culture, corporate structure, and operational practices were critically flawed.” The staff members who questioned were denigrated or ignored, and whistleblowers faced legal retribution. In one high-profile case, the former marine operations director was terminated after he filed a report on hull defects and later sued for breach of confidentiality. The Coast Guard observed, “The lack of an on-time Occupational Safety and Health Administration investigation into a 2018 OceanGate whistleblower’s complaint.” was a lost chance for possible initial government intervention. This supressing culture was carried over to the board, which was made ineffective by Rush’s autocratic style of decision-making.

5. Failure of Communication and Emergency Response

Communication practices on board the Titan were also an area of serious breakdown. The ship used a text-based system instead of voice communication in real time, creating delays and confusion in emergencies. The Coast Guard condemned this as “reflected in more general cost-saving priorities,” and called for all submersibles to have solid voice communication equipment for speedy emergency notification. The timeline after the loss of contact with Titan depicts a seven-hour lag before authorities were alerted, with OceanGate’s guide prioritizing surface searches over instant distress calls the Polar Prince called the Canadian Coast Guard at 7:10 p.m., hours after losing contact.

6. Pressure Vessel Engineering: Standards and Failure Analysis

The Titan’s implosion highlights the value of compliance with engineering standards for pressure vessels. Classical submersibles use titanium or high-strength steel hulls, materials whose failure modes are well understood and strong design codes. While composite materials are promising, they demand more sophisticated buckling analysis, material failure, and snap buckling analysis particularly because hull thickness varies with diving depth the design rules of pressurized vessels are largely developed based on their failure modes.

Not having non-destructive testing (NDT), fatigue evaluation, and extensive validation of the Titan’s hull made it prone to undetected defects. As one critic pointed out, “Void content should be normally 1-2% not the 5-12% which would create visible channels in the laminate on such a wound part.”

7. Regulatory Gaps and Industry Implications

The Coast Guard report identifies a larger problem: a lack of comprehensive regulatory guidelines for submersible use. Certification is still voluntary, and OceanGate’s ability to circumvent third-party evaluation revealed systemic weaknesses. The investigative board recommended mandatory uniform requirements and greater communication requirements for all submersibles, commercial and research. “There is a need for stronger oversight and clear options for operators who are exploring new concepts outside of the existing regulatory framework,” stated Jason Neubauer, Marine Board of Investigation chair.

OceanGate’s failure is a stark reminder that innovation needs to be balanced by engineering discipline and a culture of safety. The history of the Titan, which ended in avoidable tragedy, contains lessons that are timeless for engineers, regulators, and business leaders charged with pushing the boundaries of the ocean depths.