When the president of the United States directs nuclear-armed submarines to shift forward closer to Russia, what does this say about the world’s understanding of nuclear deterrence and its limits? The recent incident, in which President Trump counter-reacted to ex-Russian president Dmitri Medvedev’s nuclear threat by ordering US ballistic missile submarines, illuminates a deep miscalculation at the highest echelons of leadership regarding the technical imperatives and dangers of nuclear deterrence from submarines.

1. The Misconceptions of Submarine-Based Deterrence

US Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, which form the backbone of America’s sea-based nuclear deterrent, are designed to be stealthy and survivable. Each Ohio-class SSBN has as many as 20 Trident II D5 missiles on board, with a range of more than 7,500 miles and capable of carrying multiple independently targetable warheads. Their operational principle is that of not being seen, cruising huge expanses of ocean and providing a safe second-strike capability. As David Sanger noted, “US ballistic firing submarines don’t need to be repositioned. They can reach targets thousands of miles away. In fact, moving them can expose their position.” The mere action of repositioning such submarines, far from strengthening deterrence, actually serves to increase their exposure and destabilize the security they are supposed to enhance. The stealth features of the Ohio-class-from advanced acoustic dampening to extended submerged endurance-are designed precisely for keeping adversaries guessing and reducing the risk of preemptive strikes. Ohio-class SSBNs are engineered for near-invisibility, with acoustic signatures described as “a mere fish” in naval parlance.

2. The Erosion of Arms Control and the New Nuclear Arms Race

The current nuclear world is characterized by a return to the competition on arms between the United States, Russia, and China, with the last significant arms control agreement New START being due to expire in 2026. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute states that “the era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end.” Almost all nine nuclear-armed powers are currently modernizing and enlarging their stockpiles. China’s nuclear stockpile is expanding at an all-time rate, adding about 100 warheads a year, and building hundreds of new ICBM silos. The US and Russia, combined holding roughly 90 percent of the world’s warheads, are both embarking on modernization campaigns that in short order could halt decades of steady decline. The introduction of new technologies artificial intelligence, cyber capabilities, quantum computing further complicates deterrence calculations and raises the specter of inadvertent escalation.Advances in missile defense and quantum technologies threaten to erode the invulnerability of submarine-based deterrents.

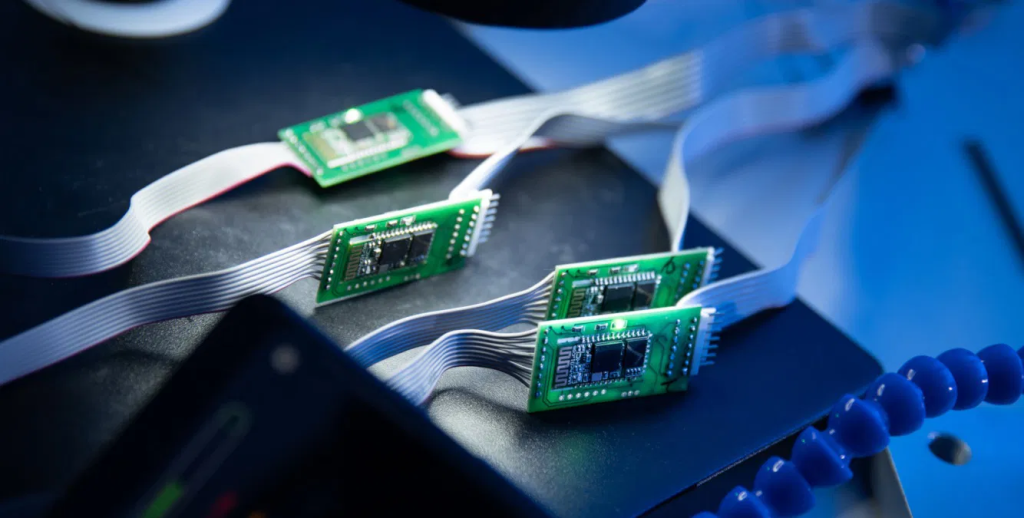

3. The Fragility of Nuclear Command and Control

As nuclear arsenals modernize, so too do their command, control, and communication (NC3) systems. The integration of artificial intelligence into NC3 by some is viewed as a means to optimize decision-making speed and accuracy. However, experts caution that “AI is unreliable. Current AI can boldly create false facts that can result in poor forecasts and suggestions, eventually distorting decision-making.” The “black box” aspect of AI programs, vulnerability to cyberattacks, and potential for “hallucinations” or misinterpretations all pose the danger of compromising the stability these systems are designed to maintain. Gen Anthony J. Cotton, US Strategic Command, warns that “we need to guide research efforts toward understanding the risks of cascading effects of AI models, emergent and unexpected behaviors, and indirect integration of AI into nuclear decision-making processes.” Probabilistic-risk-assessment techniques from civil nuclear safety are now being adapted to try and quantify the likelihood of accidental nuclear launches.

4. The Myth of Nuclear War Survivability

During the Cold War, there were those who maintained that nuclear war was “survivable.” The notorious 1980 article “Victory Is Possible” asserted that the US would be able to survive a nuclear conflict with “only” 20 million fatalities. Civil defense officials advised that “with sufficient shovels” Americans would be able to survive in sheltered structures. But contemporary modeling is much bleaker. A single 300-kiloton blast might kill more than a million people in a city the size of New York within 24 hours. In an all-out US-Russia nuclear exchange, 360 million might die practically instantly, with global climatic consequences nuclear winter, ozone loss, and crop collapse endangering billions more.Any “limited” regional nuclear conflict might put tens of millions of tons of soot into the stratosphere, leading to global famine.

5. Fail-Safe Reviews and Accidental Launch Risks

The sophistication of contemporary NC3 systems, particularly with the inclusion of advanced technologies, heightens the likelihood of unintentional, illegitimate, or erroneous nuclear employment. The US and other nuclear powers are currently performing “fail-safe” analyses to enhance protection against these events. These reviews take the experience of civilian nuclear safety into account, using probabilistic risk assessments and performance-based standards to protect against accidental launch below some acceptable level.

As put by authorities, “unless each nuclear weapon state can design its command-and-control system so that the risk of inadvertent nuclear launch is below a quantitative threshold, promises to keep humans in the loop will offer little more than an illusion of safety.” The doctrine of “defense-in-depth” stacking redundant safety systems continues to be imperative but needs to be tuned for AI-based threats.

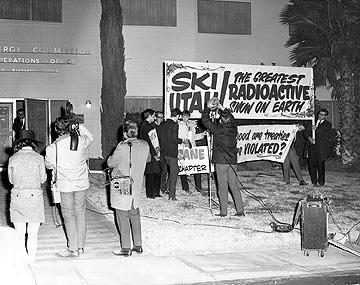

6. The Anti-Nuclear Movement: Past, Present, and Future

The anti-nuclear movement once changed international policy, contributing to a halt in above-ground testing and shaping arms control agreements. Leaders such as Coretta Scott King and Bayard Rustin connected nuclear disarmament to wider struggles for justice, showing the strength of intersectional campaigning. The movement is now challenged by different circumstances. As one commentator explains, “the risks of a nuclear war are rising, but public perception of danger is at a low point.” Support has fallen away, and focus is diluted by emergencies ranging from climate change to world inequality. And yet campaigners believe the way forward lies in coalition-building with other social movements on racial justice, climate change, and more. A new “Call to Halt and Reverse the Nuclear Arms Race” mobilized more than 20 groups, recalling the effective “freeze” campaigns of the 1980s.The technical capability, grassroots mobilization, and track-two diplomacy of the movement are still crucial strengths.

7. The Unyielding Logic of Deterrence and Its Limits

Years of diplomatic effort and technical ingenuity notwithstanding, the logic of nuclear deterrence remains inherently unstable. As one analyst described it, nuclear weapons do not guarantee security. As the recent outbreak of fighting in India and Pakistan fully illustrated, nuclear weapons cannot prevent war. They also entail enormous risks of escalation and catastrophic miscalculation especially when there’s a lot of disinformation around and can actually make a nation’s people less secure, not more. The Doomsday Clock is set at 89 seconds to midnight, a cold reminder of how close the world is to disaster. The lack of sustained communication among nuclear powers also increases the danger of misunderstanding and unintended escalation.

The technological, organizational, and political complexities of nuclear deterrence are converging at a time of increasing global instability. The history of engineering, science, and history teaches us that stability is not assured and the margin for error is woefully small.