A lost bolt. One bolt. That was sufficient to blast a door plug out of a newly rolled-out Boeing 737 Max 9, taking off from Portland, Oregon, in January 2024. The close call, potentially ending in disaster, instead was the turning point for Boeing’s new CEO, Kelly Ortberg, and the trial of the company’s engineering rigor, safety ethos, and future ambitions.

1. Ortberg’s Engineering-Driven Turnaround

When Kelly Ortberg was recruited out of retirement to take over at Boeing in August 2024, the company was reeling from decades of crisis two fatal Max crashes, recurring quality lapses, and a hemorrhaging balance sheet. Ortberg, a seasoned engineer with a history of operational discipline, moved quickly. In quick succession, he initiated sweeping cost cutting, a $20 billion capital raise, and a shake-up of leadership of its defense unit. He also brokered a new union labor contract after a seven-week machinists’ strike and sold off non-core businesses. Ortberg’s visits to Seattle, where Boeing’s main plants are located, have been described as a “positive” factor by industry analysts. “He’s showing up,” said Richard Aboulafia, managing director at AeroDynamic Advisory. “You show up, you talk to people.”

Wall Street responded Boeing shares are up more than 30% this year, and the company is expected by analysts to halve its quarterly losses compared to last year. Ortberg told shareholders in May that Boeing expects to start generating cash in the second half of 2025, with deliveries of airplanes in the period being the highest in 18 months. “The general assumption is that the culture is changing after decades of self-inflicted knife wounds,” Aboulafia said.

2. Engineering Lessons from the 737 Max 9 Door-Plug Crash

The crash on Alaska Airlines uncovered deep failures in Boeing’s quality control and production systems. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) found that four critical bolts were missing on the door plug a failure that “never should have happened,” NTSB chair Jennifer Homendy told. The investigation discovered that Boeing documentation and regulatory practices were insufficient, from a “single point of failure” with no record of who performed the reinstallation. “Boeing employed a single point of failure, which was an individual not filing or recording a record. That was a vulnerability in the system,” Homendy said. The crisis was worsened by skill loss among workers during the pandemic and undertraining of new starters. The FAA responded by reducing 737 Max production to 38 aircraft a month and placing more inspectors within Boeing’s Renton factory, as well as requesting a full overhaul of the company’s safety management system and supply chain management.

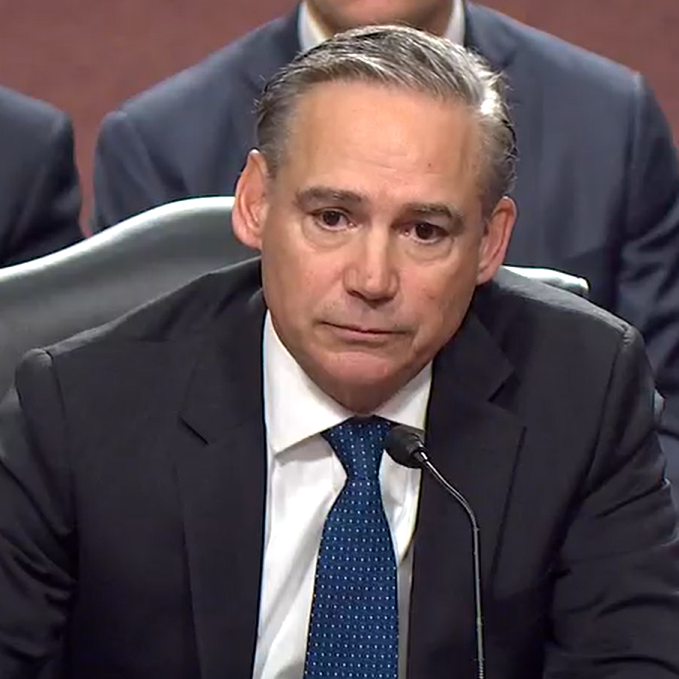

3. FAA Oversight and the Path to Higher Production

The FAA’s monitoring of Boeing is unprecedented. Administrator Bryan Bedford described Boeing’s development as “real, but still embryonic,” and emphasized that “we’re a long ways away from saying we can let our guard down.” The FAA will conduct a comprehensive examination of Boeing’s supply chain and quality control procedures prior to approval of any production rate increases. The agency has also provided a program whereby Boeing may perform some of the inspection work, albeit under close monitoring. “We will not accelerate 737 monthly production until we are certain the company can assure safety and quality and produce more aircraft,” FAA said in a statement after the Alaska Airlines incident. Certification for the Max 7 and Max 10 configurations remains outstanding, and this contributes to Boeing’s ramp-up ambitions.

4. Production, Certification, and Financial Pressures

Boeing’s monetary recovery is very much tied up with its ability to deliver more planes. Producers are paid when they deliver, therefore increased production rates are a top priority. But the company’s production backlog and ongoing FAA limitations create a high-wire act. “47 a month I think is the hard break,” said Douglas Harned, Bernstein’s lead aerospace analyst. Boeing also has a high inventory base, but absent regulatory clearance, improvements in cash flows are constrained. The defense industry, meanwhile, remains stuck with losses on fixed-price contracts most recently the KC-46 tanker and Air Force One deals, both of which have gained public and political attention due to delays and cost overruns.

5. Engineering and Regulatory Culture Shifts

The FAA’s regulatory culture has deepened fundamentally since the Max crises. The agency contracted more of an “audit plus inspection” scheme, placing more inspectors in the factory floor and using more data-driven monitoring. The FAA also beefed up its Organization Designation Authorization (ODA) program, requiring manufacturers to protect employees performing FAA work from employer interference and reporting all allegations of interference directly to the agency under a 2022 policy update. Boeing’s new safety management system, mandated by the Aircraft Certification, Safety, and Accountability Act of 2020, will formalize hazard identification and risk management across all operations. “A good Safety Management System is the structure and framework of a safe manufacturing operation and will be a key element of improving Boeing’s safety culture,” FAA Administrator Michael Whitaker stated.

6. The Elusive New Midsize Aircraft: Engineering, Market, and Strategic Challenges

While Ortberg’s immediate priority is stabilizing Boeing’s core business, the company is coming under growing pressure to bring to market a new mid-market aircraft. The so-called “Boeing 797” or New Midsize Aircraft (NMA) has long been on the table as a replacement for aging 757s and 767s. The new plane will be a composite fuselage, two-aisle aircraft with high-bypass turbofan engines and 220–270 seats and an maximum range of 5,000 nautical miles to compete against the Airbus A321XLR. Yet, the work has been halted several times due to technical, financial, and organizational considerations. Boeing has talked to 57 airlines and committed to building its next new aircraft in Washington state but not necessarily stated that the project is the NMA. The timeline for a launch is uncertain, with analysts predicting that even if approved, the plane would not go into service before the 2030s.

7. Competitive and Technological Pressures

The time lag in bringing a new mid-market plane has allowed Airbus to dominate the segment on the back of the A321XLR, with a 4,700-nautical-mile range and up to 244 passengers. Airlines United, Qantas, and Icelandair have ordered from Airbus, and startup entrants such as JetZero are developing blended wing body designs which will continue to disrupt the market by the end of the decade with revolutionary efficiency advances. Boeing engineers also await new engine technologies, such as open-rotor concepts, to mature before pursuing a cleaner-sheet aircraft. “We’re going to start with a clean sheet of paper again I’m looking forward to that,” former CEO David Calhoun said in 2020, signaling a deliberate, technology-driven approach. Despite the turbulence, Ortberg’s leadership has instilled a renewed sense of engineering discipline and transparency at Boeing.

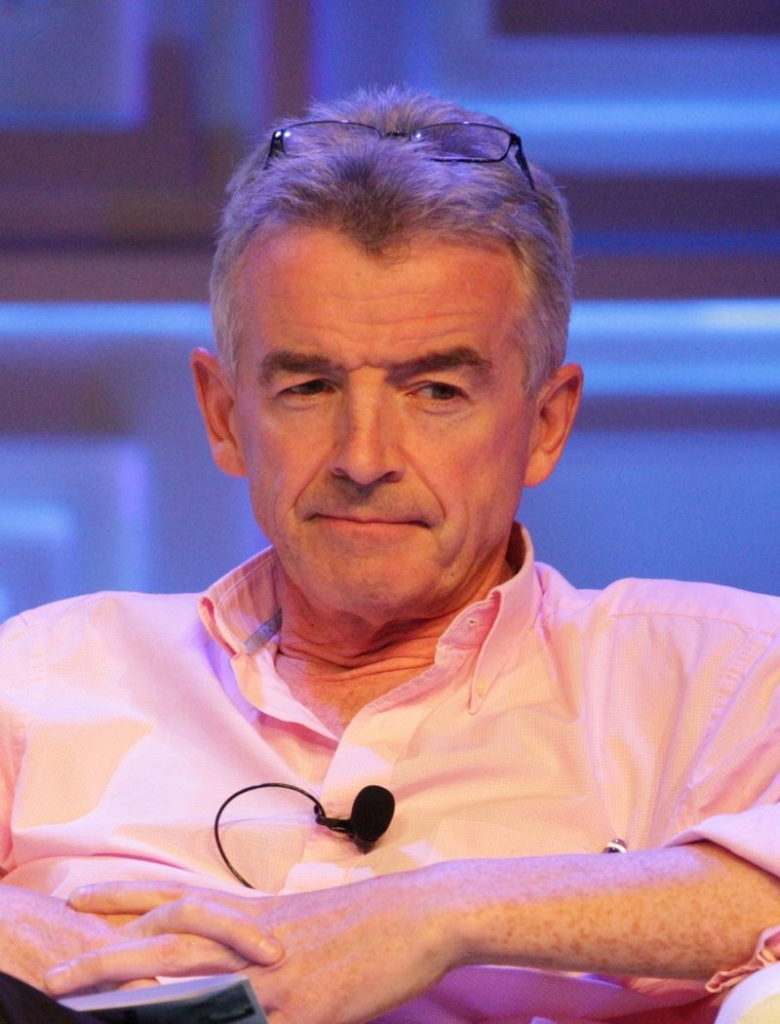

“I continue to believe Kelly Ortberg, and Boeing Commercial Airplane unit CEO Stephanie Pope are doing a great job,” said Ryanair CEO Michael O’Leary. “There is no doubt that the quality of what is being made has improved significantly.” Yet while the FAA maintains its production cap and the world holds its breath to find out what’s going to happen next, Boeing’s head start is a risky bet of engineering, regulatory faith, and strategic expertise.