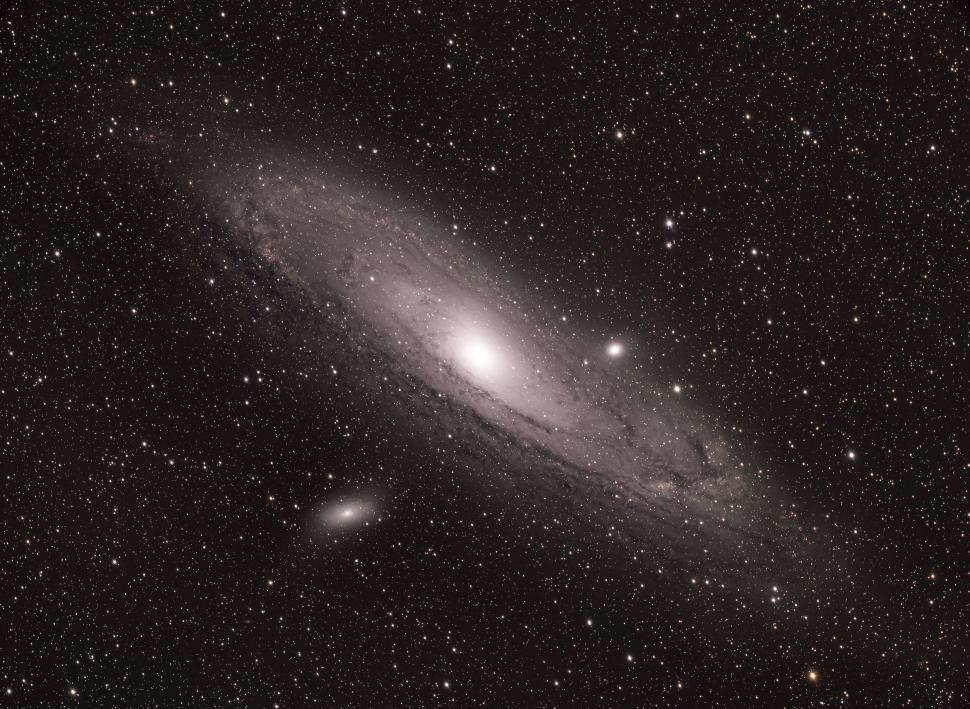

Can 200 million stars in one galaxy be cataloged, and what does it take to accomplish this task? The decade-long mosaic of Andromeda by the Hubble Space Telescope not only provided the answer to this question but also rewrote what humans can learn about their galactic neighbor. This landmark project, the most detailed and sharpest image of Andromeda ever created, is an engineering, data science, and astronomical triumph.

1. Hubble’s Mosaic: A Decade in the Making

The Andromeda mosaic is not a single picture, but the result of over 1,000 Hubble orbits and more than a decade of painstaking observation. The final product is a 2.5-gigapixel panorama, made up of some 600 individual fields of view, precisely aligned and calibrated. “Basically, with Hubble we can get into huge detail on what is happening on a big scale across the entire disk of the galaxy. You can’t do that with any other big galaxy,” University of Washington principal investigator Ben Williams said. The project combined two ambitious projects: the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury (PHAT) and the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Southern Treasury (PHAST), each making observations of different regions and wavelengths in order to assemble a comprehensive map of the structure and history of the galaxy. The disk in the south, observed by PHAST, was especially revealing, giving clues of Andromeda’s turbulent history and merger record by the detection of characteristic stellar populations and structural perturbations.

2. Engineering the Ultimate Space Telescope

Hubble’s ability to view individual stars in Andromeda some 2.5 million light-years distant is founded on its 2.4-meter Ultra-Low Expansion Glass® mirror and its Ritchey-Chrétien Cassegrain design, chosen for size and excellent off-axis imagery. But the journey was bumpy. At its launch in 1990, Hubble’s main mirror suffered from a spherical aberration due to a 1.3-millimeter error in the test equipment, producing fuzzy images. NASA’s fix was an optical engineering masterstroke: astronauts mounted corrective lenses and new cameras on the first servicing mission to restore and even surpass the original designed performance of the telescope. The Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) and COSTAR corrective system became “a giant pair of spectacles, refocusing the light and enabling the instruments to see clearly again” after the repair.

3. The Science and Art of Astronomical Mosaics

It took more than just images to build the Andromeda mosaic. It required an advanced technique of data reduction. The Hubble Advanced Product (HAP) pipeline, which includes Multi-Visit Mosaics (MVM), stacks exposures made at various times and in different programs onto a shared pixel grid so exposures can be stacked and compared seamlessly between filters and detectors.

The 2.5 billion pixels of the mosaic are not only a technical curiosity; they are a scientific asset, allowing for the cataloging of 200 million individual stars each resolved as an independent point of light, though separated by enormous cosmic distances. Detector artifacts, cosmic rays, and chip gaps are all accounted for by state-of-the-art software, resulting in a scientifically accurate and visually stunning final image with little disambiguation from instrument flaw.

4. Andromeda’s Anatomy: Dust, Stars, and Black Holes

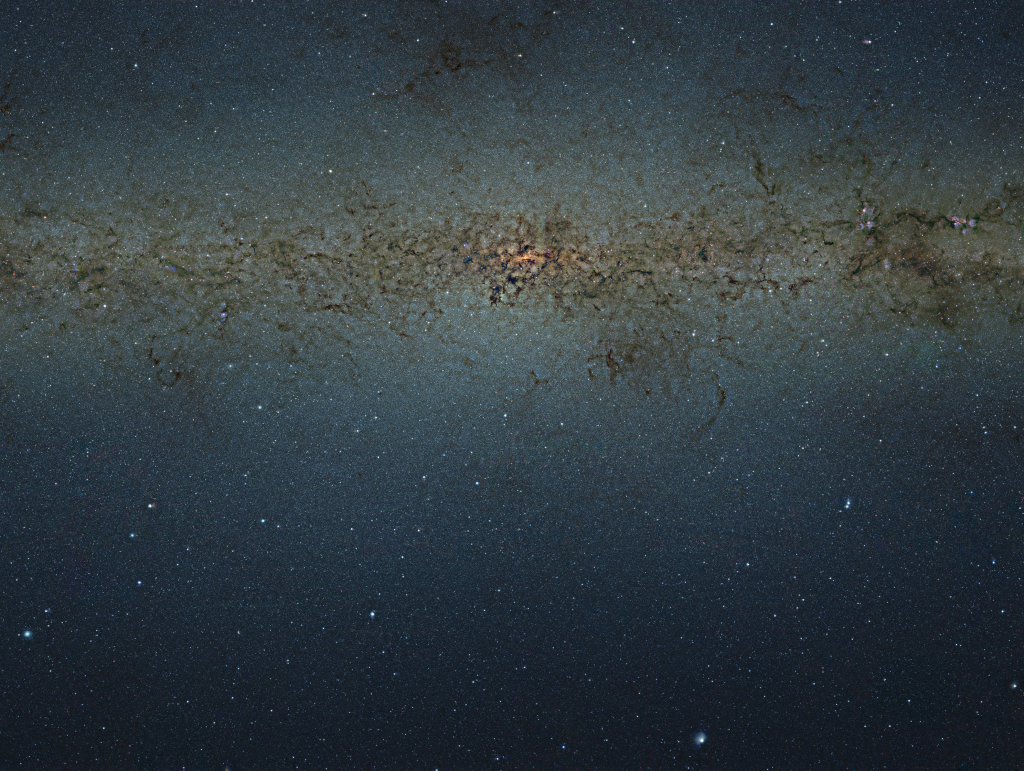

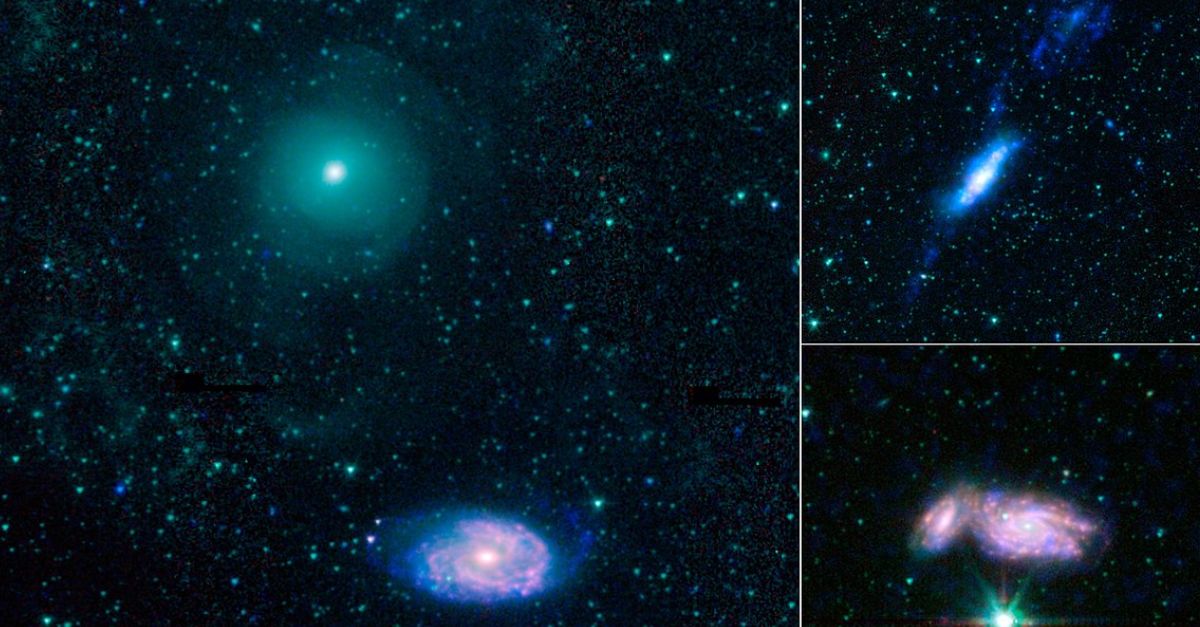

The mosaic reveals Andromeda’s intricate anatomy: reddish-brown lanes of dust that are incubators for new stars, enormous star-forming regions, and a dense central bulge where stars are too densely packed to be visible as individual points. The tilt of the galaxy 77 degrees from our position gives us a close to edge-on view, compared by astronomers to “seeing a fried egg from the side.” Foreground stars from our Milky Way, readily recognizable by their diffraction spikes, add punctuation to the picture. Among the most striking features is the supermassive black hole at the core of Andromeda, weighing more than 100 million solar masses. New observations with both the Hubble and Spitzer telescopes have charted out streams of gas and dust filaments swirling into the black hole, offering a direct look at the process of being fed. “The filaments creep up to the black hole little by little, and in a spiral, just like the water spirals down the hole in the sink,” said Almudena Prieto of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in a close accretion study.

5. A Galactic ‘Train Wreck’: Shadows of Collisions in the Past

Andromeda’s current appearance is characterized by mergers and interactions of galaxies in the past. Evidence of a glorious past collision comes in the form of the presence of the dwarf galaxy M32, now a stripped core. “Andromeda’s a train wreck. It seems to have gone through some kind of episode that caused it to form a tremendous number of stars and just then shut off,” said Daniel Weisz of UC Berkeley. The turbulent structure of the southern disk and the Giant Southern Stream a tidal debris field are fingerprints of these ancient collisions. These features, mapped in beautiful detail by the Hubble mosaic, help astronomers reconstruct the galaxy’s history of evolution and discover how mergers of this kind fuel star formation and galaxy morphology.

6. The History Milestone: New Cepheid Variables and the Universe’s Size

Andromeda’s history is entwined with the history of modern cosmology. At the beginning of the 20th century, astronomers debated if the Milky Way was the entire universe or just a single galaxy among others. The answer arrived with Henrietta Swan Leavitt’s discovery of the period-luminosity relation in Cepheid variable stars, by which distances were measured across vast expanses of space. Edwin Hubble’s identification of a Cepheid in Andromeda, marked with the now-infamous “Var!” on a photographic plate, proved that the “spiral nebula” was actually a galaxy far beyond the Milky Way. “He revolutionized our view of the universe overnight. This finding is the most significant in all of astronomy during the last 400 years, dating back to Copernicus and Galileo’s discoveries,” said John Mulchaey, Director of Carnegie Observatories on the impact of Hubble’s research.

7. From Hubble to the Future: Opening the Cosmic Frontier

The Hubble mosaic of Andromeda is not just a picture, but a living data set. It provides important context for upcoming missions, the James Webb Space Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, to image the galaxy with even more efficiency and depth.

Roman’s wide-angle vision will allow astronomers to capture the equivalent of 100 Hubble photos in a single exposure, further deciphering Andromeda’s star streams, merger history, and stellar populations as the next generation of space telescopes start to arrive. The Hubble mosaic of Andromeda is a witness to human potential bringing together the best of optical engineering, data science, and astronomical interest. As Jennifer Wiseman, Hubble’s senior project scientist, put it: “It’s phenomenal that human beings, who have looked at Andromeda since time immemorial, are suddenly able to see this much detail. It’s a gift. We must take a moment to be awed. Because it’s beautiful.”