It began with a congressional push and a query: Can the U.S. Air Force really fulfill the vision of cheap, mass-produced autonomous fighter jets ahead of the competition? The House Armed Services Committee has finally signaled its intentions, directing the Air Force to submit to Congress by January 16, 2026, its plan for full production and resource requirements for Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) Increment. It is a turning point for the Pentagon in its drive for a game-changing, AI-centric air force.

1. The Congressional Mandate and Program Milestones

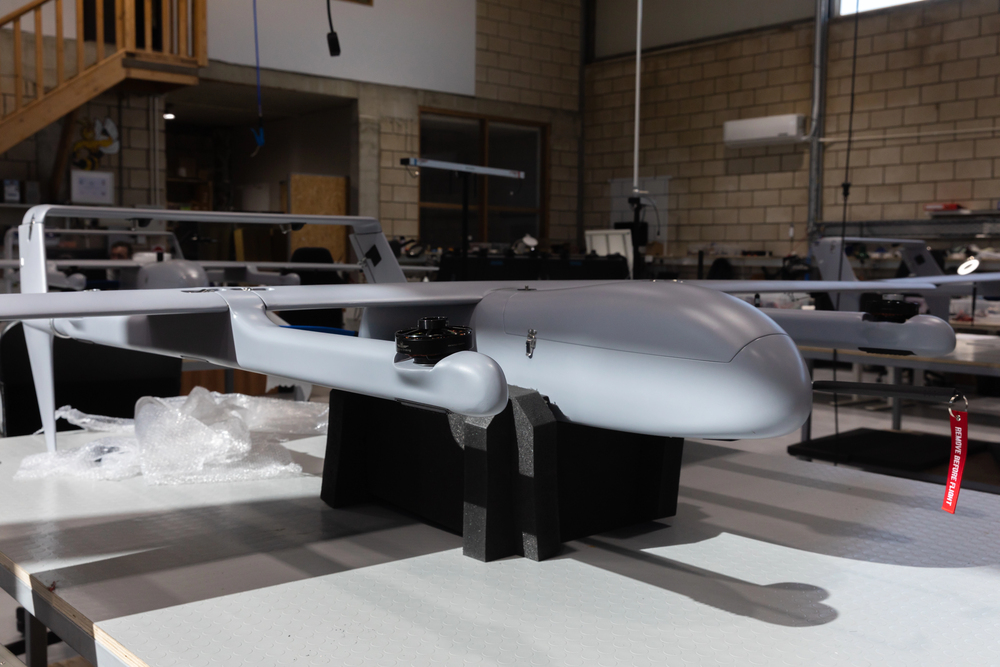

The HASC amendment, led by Rep. Mike Turner, demonstrates bipartisan urgency. The committee is awaiting the Air Force to go ahead with full-rate production of Increment 1 as soon as possible following successful flight demonstrations,” reads the amendment. The Air Force shall provide a complete transition plan for bringing CCA prototypes, currently represented by Anduril’s YFQ-44A Fury and General Atomics’ YFQ-42A Gambit, into mass production, as well as a full accounting of resource needs.” This cry for openness comes as the program is at a critical juncture: ground testing is underway, with first flights for each example anticipated before the close of 2025. The service looks toward a competitive downselect in fiscal year 2026, followed by the start of Increment development, envisioned to enhance mission opportunities and integrate new technologies.

2. Technical Leap: Range, Readiness, and Rapid Fielding

The CCA prototypes will have a minimum range of 700 nautical miles, overtaking both the F-22 Raptor and F-35A Lightning II. This increased range is not merely a technological sleight of hand; it’s a direct response to the problem of combat in the vast Indo-Pacific theater and countering proliferating long-range opponent systems. Beale Air Base in California, where the U-2 is stationed, has been charged to be the Aircraft Readiness Unit for CCAs, so that the drones are on call to deploy anywhere in the world at short notice. The Air Force plan is to keep these half-autonomous planes in “fly-ready” state, flying fewer sorties a day and with a smaller footprint in terms of personnel than conventional fighter units.

3. Autonomy and Human-Machine Teaming

In the middle of the CCA program is a fresh concept of AI-facilitated autonomy. The drones will be designed to fly along with, and be manned by, fifth- and sixth-generation fighters and conduct intricate missions ranging from electronic warfare to air combat maneuvers. The five unnamed contractors have developed the autonomy software, which is separate from the purchasing of hardware, allowing the Air Force to select the most leading-edge solutions for each category.

“Together, Anduril and the United States Air Force are leading the development of a new generation of fighter aircraft with semi-autonomy that will revolutionize air combat,” said Jason Levin, senior vice president of air dominance and strike at Anduril. The open-architecture, modular design strategy rooted in the Autonomy-Government Reference Architecture (A-GRA) facilitates the integration of new capabilities in real time and ensures interoperability between platforms and services.

4. Scaling Through Engineering: Challenges in Manufacturing and Supply Chains

The objective of the Air Force is nothing short of flying thousands of CCAs for a fraction of the cost and time that conventional fighter aircraft would take. David Alexander, head of General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, emphasized the industrial imperative: “The CCA program is emphasizing simplicity, affordability and mass. For that speed to capability. companies have to believe in what they are building so that they can be able to go directly into production, and the speed of getting the proper sensor systems with open architecture, so that the system can grow in the future. And don’t downplay the supply chain significance worldwide. and having parts and kitted where they need to be, in the timeframe that the Air Force” will be asking manufacturers to provide. Predictable, reliable production volume projections from the Air Force must be available to allow supply chains to be leveled and not congested. The industrywide consortium approach now well over 30 companies aims to foster competition and resilience with both legacy OEMs and nontraditional, venture-backed firms.

5. The Software-Hardware Divide and Modular Innovation

By decoupling software and hardware acquisition, the Air Force will be free to pursue best-of-class and maintain ongoing competition. This modularity eliminates risk of past program delays caused by software integration problems. The A-GRA modularity allows for the integration of software updates and new sensor packages without impacting flightworthiness certification, accelerating innovation cycles. This validated commercial and defense paradigm will be a building block for future increments and allied interoperability.

6. Growth of the Industrial Base and Nontraditional Entrants

The selection of venture capital-backed firm Anduril as a CCA prime is a shift in defense procurement culture. The Air Force’s willingness to do business with nontraditional contractors is intended to revitalize the industrial base and promote private investment in defense innovation. “This coming phase of CCA is a very hopeful development for future Air Force autonomy,” notes the Congressional Research Service, citing the program’s multiyear funding and firm trajectory toward operational deployment. The open competition on Increment 2, and the opportunity for bidders eliminated in Increment 1 to rejoin the competition, is designed to keep technological momentum going and avoid complacency.

7. Risks, Timelines, and the Strategic Imperative

While momentum is accelerating, the timeline remains close. The Air Force estimates to have “in excess of 100 [CCAs] ordered or delivered at the end of the [Future Years Defense Program],” namely by September 2029. Intelligence projections that China will be “ready in 2027 to perform a successful invasion” of Taiwan injects a feeling of urgency and skepticism about whether the U.S. will be able to deploy tactically meaningful numbers of CCAs on time. Congressional panels have complained that current policy may not be aligned with the tempo of enemy progress or with the need for “affordable mass” in the near term.

The direction the CCA program takes will be a function of the Air Force’s ability to turn engineering innovation, modular software, and flexible manufacturing into operating reality before the technological window of opportunity closes.