The monumental engineering lesson contained in the Starliner program did not come as a dramatic splashdown. It came as a gradual and creeping building-up of little, cumulative propulsion uncertainties-thrusters which went adrift, helium which would not remain in place and test evidence that explained much and yet left painful gaps.

The astronautic mission of Starliner has been redefined by NASA as the next flight of the spacecraft was transformed into an uncrewed, cargo spacecraft. It is no longer the automobile attempting to demonstrate that it can transport human beings on a daily basis, it is attempting to demonstrate that it can be relied upon to act in a predictable manner when the time comes. These are the program-level and technical-level pressure points which now determine what the Starliner-1 has to show.

1. A crew spacecraft being treated like a cargo test article

NASA verified that the second Starliner will be an astronaut-free mission that will boost supplies to the ISS, but will not be launched before April 2026. Validation is the key value of the mission: the mission is intended to test updated propulsion hardware in the actual thermal, attitude, and duty-cycle conditions that can only be approximated in ground testing. This mission is still required to perform similarly to a station logistics run, which includes rendezvous, proximity operations, docking, and an on-time departure, since these are the regimes that the propulsion system had proven weak previously.

2. The risk-concentrating service module thruster layout

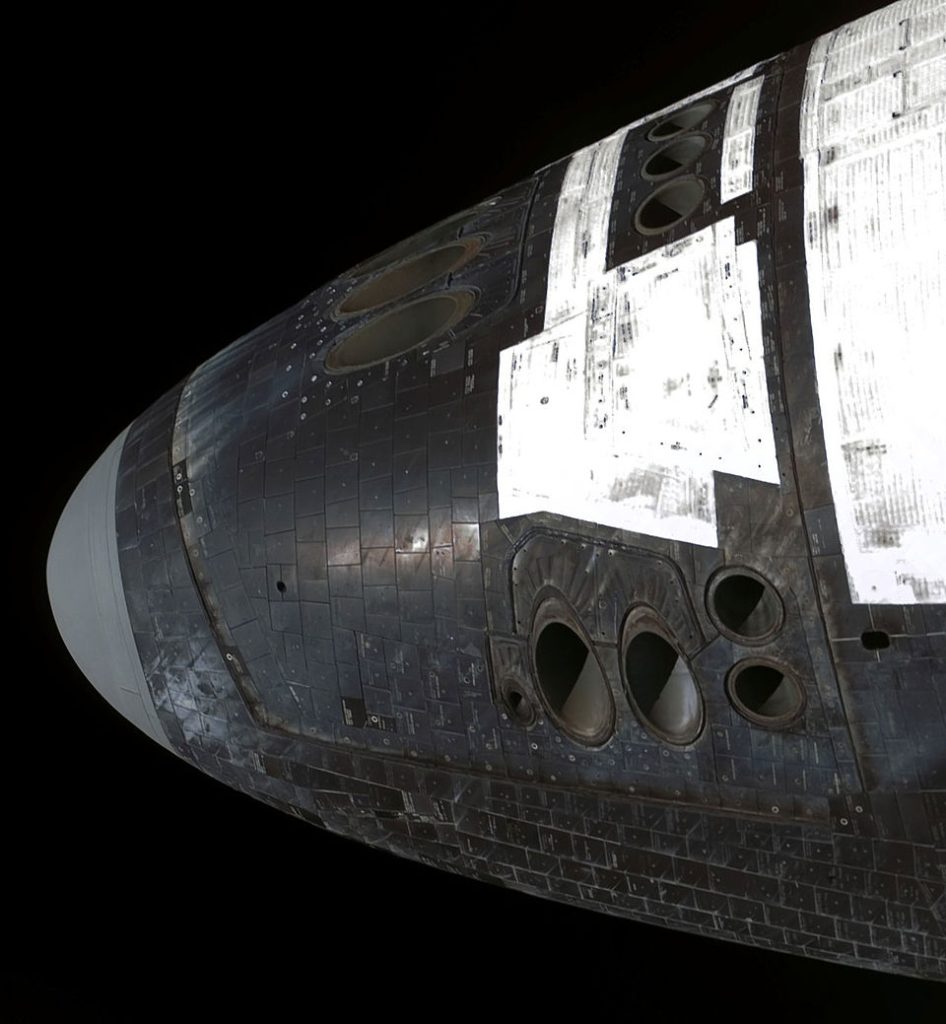

The service module aboard Starliner has 28 RCS thrusters and 20 OMAC thrusters with four RS-88 launch abort engines supporting them. The RCS set takes care of the little, frequent impulses needed to manage the attitude control and final approach precisely the stage at which repeated firings have the potential of adding heat to valves and plumbing. The architecture possessed a diagnostic disadvantage as well: the service module is thrown away prior to landing and this prevents close inspection of the hardware on post-flight which endures the most thermal and contamination environment.

3. A small Teflon seal that has exorbitant mission impact

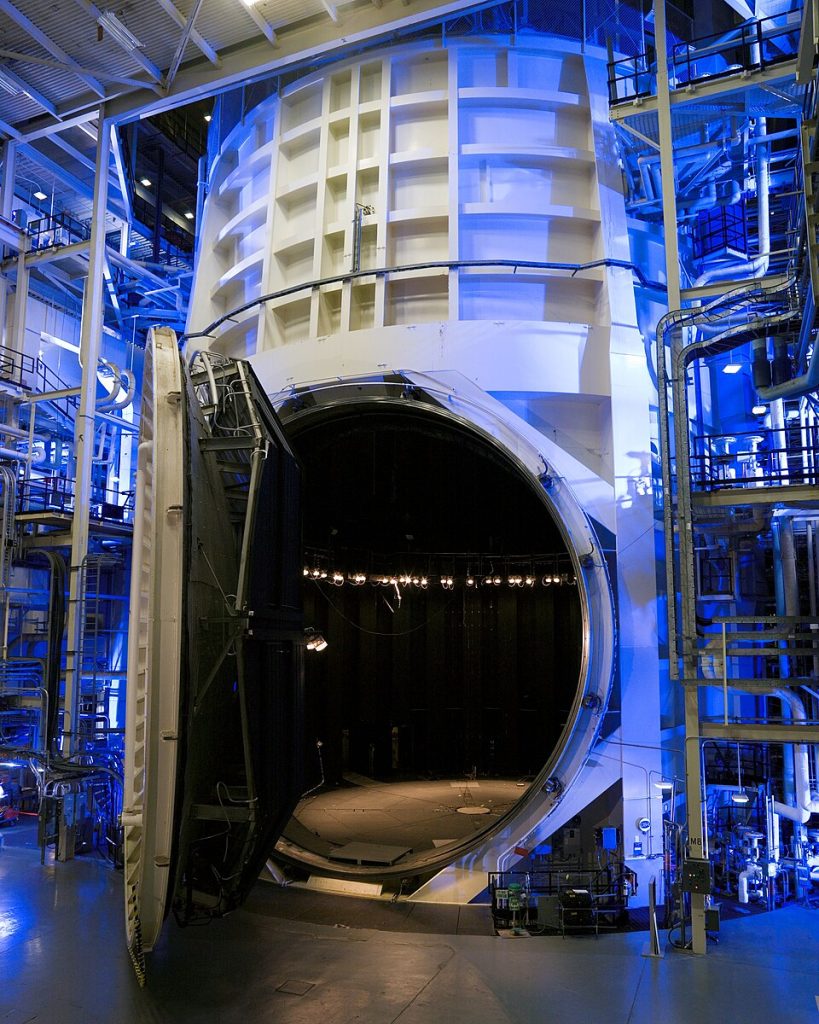

At the 2024 crew flight test approach to station, five service-module RCS thrusters failed. The most critical failure mode was the small Teflon poppet like seal located within the valve. The seal might become deformed and incapable of supplying propellant to the thruster under hot weather conditions exacerbated by repeated firing and exposure to sunlight. White Sands Test Facility ground work assisted in the reproduction of the thermal sensitivity, but NASA also admitted some limitations regarding proving a one-on-one correspondence between the test rigs and the behavior in space.

4. Helium losses that make margins doubtful

Starliner has a propellant feed system that is pressurized with helium, and any leak wastes gas, and also shaves away the capability of providing more stable propellant flow as the program continues. The crew test flight experienced five service module RCS system leakages of helium- one identified before the launch and four on board. The engineers estimated that the helium would be safe to come back, but when the leak uncertainty was combined with the thruster uncertainty, they ended up with the type of compounded risk that the human-rating processes are supposed to avoid.

5. The reason why autonomous return is not similar to safe crew return

Starliner is capable of undocking and deorbiting on its own, which NASA has highlighted in publicly-facing Q&A content on the available options to return to Earth. The difference is that autonomy is controllable, but does not necessarily behave robustly when presented with poor propulsion performance. The choice of decision-making by the NASA crew was dependent on the ability of the propulsion and helium systems to be reliable on a variety of return contingencies, rather than the possibility of the vehicle following an optimal sequence just twice.

6. Loopholes in verification that continue to reoccur in other forms

The propulsion problems with Starliner fall within a longer history of test-and-integration problems. The orbital test flight of 2019 did not make it to ISS as end-to-end integrated testing was found wanting due to software and timing issues. Subsequently, redesign effort was motivated by the corrosion of oxidizer valves; additional rework was motivated by parachute link strength and flammability. These issues all have a common cause but when combined, they define an organization that continually finds system-level problems when an organization can no longer afford later than a human spaceflight program.

7. The doghouse and plumbing modifications that are now required to endure actual duty cycles

According to NASA and Boeing, they are conducting thrusters using intense ground campaigns, which included thermal cycling, leak-rate testing and design change validation. The uncrewed cargo mission is the first occasion to demonstrate that revised thruster housing (doghouse) assemblies and changes to the helium-system act properly when subjected to orbital heating, eclipse cycling, and dense choreography of rendezvous and docking. In the case of Starliner, the notion of success is not a lack of failures, but a consistent operation to the point of uncertainty mitigating to allow a crewed certification case.

8. What cut-down flight bookings portend with regard to operational reality in the near term

NASA and Boeing redesigned the Commercial Crew flight plan such that ordered Starliner missions reduce to definitively ordered four instead of six but two of them would be an option, and the contract value is lowered by 768 million to 3.732 billion. That redefines the number of operational experiences Starliner can have before the retirement of the ISS in 2030. Reduced flights imply reduced opportunities to learn about insidious wear-out modes, workmanship drift or off-nominal edge cases, which only manifest themselves in service, precisely the sort of knowledge that transforms a spacecraft into a certified object rather than a routine one.

The current Starliner-1 is not about demonstrating ambition anymore, but demonstrating repeatability. Cargo provides NASA with an opportunity to require actual performance without having astronauts on the front line of any propulsion uncertainty. In case the vehicle comes back, on one side, of this flight with clean propulsion telemetry and level pressurization behavior, the program would have obtained something more difficult to purchase than equipment: Confidence based on flight conditions.