A service pistol does not often feature in the front line of the firepower of a unit, yet it has one of the most savagely specific job descriptions: maintain the working situation when the plan fails. A long gun that is either empty, snagged, or just too large to fit in the space is where the handgun comes into play to work within the limits of the reach of the arm and the utmost stress.

Over two hundred and fifty years, American sidearms continued to evolve in form-flintlocks to revolvers to high capacity autos to modular chassis guns yet the very criteria used to select them remained hopelessly old-fashioned. The ease and strength and a book of arms that will support the hands when they are cold or wet, or when the hands are trembling, were more important than novelty.

1. Model 1775 Flintlock Pistol

A flintlock that was a product of a British design was adopted to become the Model 1775 before standardization became doctrine, formerly an attempt to bring some order to a bewildered parley of chambers of the Continental Army, which were of the so-called variety of the privately-purchased pistol. Being a.62-caliber, smoothbore, single-shot handgun, it was the first effort to bring the equipment of last resort to a standard sufficient to be issued, maintained, and trusted. Its shortcomings were evident even during its own time, with slow reloading, lack of accuracy, and violent ergonomics, but its concept was timeless the sidearm lives in feet, not yards.

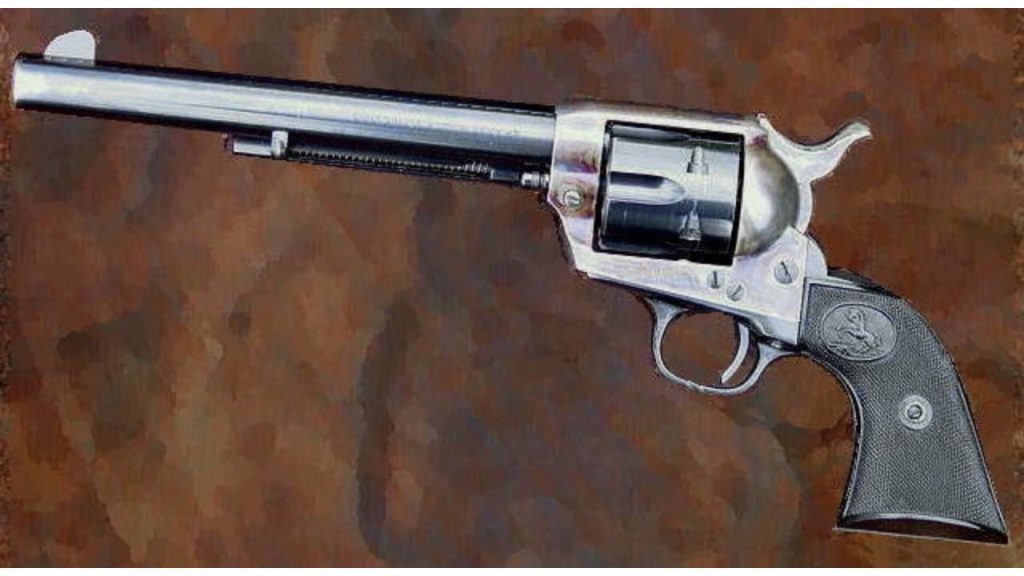

2. Colt Single Action Army (M1873)

The Colt Single Action Army became a reliable point of reference due to the way the hard conditions became a way of life. Dust, mud, gruesome saddle carry, and even lengthy periods of dereliction were the order of things, and the mechanical simplicity of the revolver served to make it predictable. It even came in the break away to metallic cartridges and eliminated many of the points of failure of the previous ignition and loading techniques. In the case of mounted troops and frontier expeditions, it was the type of handgun that did not have to be given a second consideration it was an underestimated trait when all other considerations needed to be taken into account.

3. Smith and Wesson Model 3 Schofield

Top-break of the Schofield was not glamour but constraint speed. A cavalryman who was a master of a horse had but little time, and little hands, and a revolver that could be unscrewed, emptied and reloaded very quickly transformed what a backup might mean in practice. In its design, it was emphasizing a common trend in the development of sidearms: once the handgun is literally an emergency weapon, the survival strategy will involve reload options and not a training-note.

4. Colt M1892 and the Return to .45

The switch of the Army to the Colt M1892 in .38 Long Colt appeared contemporary on paper swing-out cylinder, two-action, quicker in handling, but field experience was penal to the cartridge selection. That discontent led to the use of heavier bullets again, which culminated in the Colt New Service Model 1909 and the traditional belief that a future pistol cartridge must not be less than.45 caliber. It was never the nostalgia that lasted forever, but feedback which was the engineering lesson. Reliability in the effect of the terminal shot is now a constituent of the reliability formula when a sidearm is withdrawn at an offensive distance.

5. The M1911 and M1911A1

The marriage of a workable cartridge and a pistol architecture that increased to mass issue, mass maintenance and mass familiarity made the M1911 dominant. The .45 ACP, originally designed by John Browning and used with the pistol in 1911, was also an initial technical line in the sand because it was the earliest U.S. military pistol cartridge that used smokeless powder.

The subsequent M1911A1 perfected the human interface – minor ergonomic modifications that became significant when fine motor coordination was lost. The extended service of the platform in the various wars made it more than a handgun; it became a reference point of what the troops wanted a works every time sidearm to feel like.

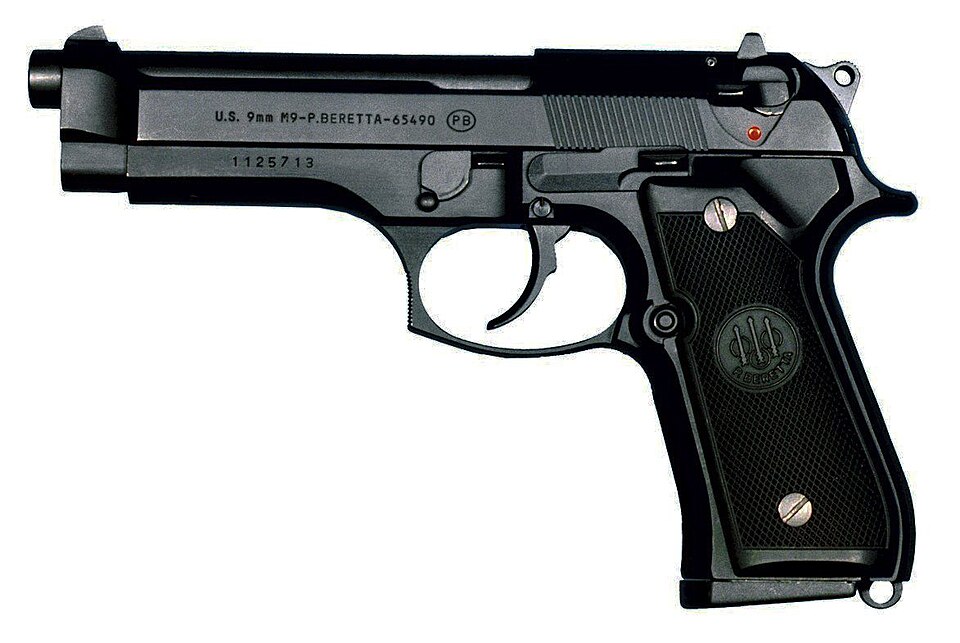

6. Beretta M9 and M9A1

The M9 brought the contemporary trade that continues to dominate service pistol debates: ample number of rounds on board or higher diameter. The 15 rounds of magazine and controllability of the M9 were useful features, but soldier confidence was not always in line with the specification sheets. A vast survey of returning Army found soldiers reported the greatest number of stoppages when using M9 at 26 per cent when engaged and this is a perception issue that even upgrades could not overcome easily. The accessory rail on the M9A1 recognised a new fact- liquidity- handgun increasingly required the lights to work into low visibility and the modifications to the magazine and finish were supposed to minimise the chances of sand on the friction areas.

7. Modular Handgun System, SIG Sauer M17 and M18

The M17 / M18 helped the U.S. make a shift in thinking about a single pistol, single configuration to one that was based on a series of internal chassis. It had delivered 200,000 pistols by November 2020, and made simultaneous deliveries to all branches in the first month. One of the core mechanisms that can be reconfigured with grip modules and slide lengths to minimise training friction and ease sustainment is the Fire Control Unit concept, an engineering hook. With the classic use of the sidearm included always, used infrequently modularity has less to do with customization culture and more to do with the similarity of the familiar trigger, controls, and maintenance logic to all jobs and body types.

In these designs, the only glue is not style and armament. Institutional memory is concentrated on failure modes: what breaks, what jams, what corrodes, what is too slow to reload and what is too hard to keep running once sleep and time have elapsed. The sidearm is the gear that is carried till the time no one has planned to think about when distance fails, the rifle is silent, and some kind of a mechanism must speak instantly.