Ownership of guns can not collapse on paperwork, but on goodwill. Most of the lawsuits that otherwise conscientious gun owners get into usually begin with simple choices driving across a border, leaving a handgun in a car, lending a rifle to a relative or walking into a building with the wrong rules stenciled on the door.

The issue is institutional: the US gun legislation is divided into federal regulation, state laws, local regulations, and corporate-property regulations. An ordinary day may span over different jurisdictions and each of them can vary the meaning of lawful possession.

1. Traveling with a carry permit that stops working at the border

Carry reciprocity gives an illusion of continuity. One state could have a permit that is legal and nonsensical in another state, with the legality of the permit changing half-way down the road without any alteration in the actions of the owner. The compliance burden does not only relate to the recognition of the permit, it may also entail the manner in which the firearm has to be carried, whether it would be loaded or not and where it would be stored during a transit. Once it is found that a mismatch occurred during a traffic stop or a post-event incident, the person may end up arrested, seized, and criminally charged as an unlicensed carrier.

2. Treating “out of sight” as “secure storage”

Secure storage is not a vibe, nor is it in most locations a legal requirement. Even when it feels like the gun has been put away, a drawer, glove box or a console can be easily accessible, and the legal risk increases when the gun is accessible to the minors or to other unauthorized individuals. The patch up state-by-state patch up: twenty-six states have passed secure storage (child access prevention) bills, yet the standard of triggering liability varies: some regimes look at whether a gun is not in the owner’s possession and immediate control, whereas others look at whether a child actually accesses the weapon. The most powerful variants also consider the access by adults who are not allowed to possess them, increasing the risk beyond households with children.

3. Modifying a firearm until it becomes a different legal category

Bonafide changes in physical appearances can lead to a massive reclassification in legal terms. Reducing the length of a barrel below a limit, assembling a configuration that qualifies as an NFA item, or like assembling parts in a manner that regulating authorities consider its creation to be an NFA item may place a gun into a highly controlled category. The risk is a procedural one, rather than a mechanical one: once an item is deemed as under NFA-regulatory, its owner exposes himself or herself to the status of registration, documentations, and transfer regulations. The configuration that may appear like a garage project, could become a possession case when it is configured in a way that is not considered legal by the law.

4. Waiting too long to report a gun that went missing

When a lost gun is not reported in time, it may turn into the second crime. In states that mandate reporting the loss or theft of firearms (only 17 states in total per the report), it is the part of the legal control mechanism designed to restrict the deviation into the illegal markets. That obligation redefines the risk of the owner, as well: in the case a gun is found in a criminal investigation and nothing is reported, this non-occurrence may be understood as negligence or even worse. The reality on the ground is that a wait of time can make a bad day a case file.

5. Carrying after drinking, even without drawing the firearm

Most jurisdictions view firearms and intoxication as a problem of carrying, but not a problem of use of force. The enforcement does not need the use of a shot or even a threat, the combination itself can be sufficient to impose criminal penalties and allow consequences. The legal theory is simple: impairment is a loss of judgment, and public carry is restricted as a luxury with limitations. This is in fact one of the most preventable points of exposure since this can be controlled by securing the firearm prior to alcohol getting into the mix.

6. Lending or selling informally when the law expects a formal transfer

In most states, it is not a exemption of transfer. The federal law already forbids the transfer of a firearm to a prohibited individual with knowledge, and state regulations may further impose such conditions as a background check, dealer processing, or special paperwork even in case of a personal sale. This is not the point of death of the risk: in case the gun is found in the future when the crime is happening, investigators go backwards in the trail of ownership and transfers. Informal transactions may result in the original owner being incapable of demonstrating a legal transfer, or even being involved in an illegal transfer.

7. Assuming self-defense standards travel well across state lines

Use-of-force law is state law, and the thresholds are incomparable. In certain jurisdictions there is a duty to retreat in some situations whereas other jurisdictions adhere to stand your ground systems. The territory is expansive: there are over two dozen stand-your-ground laws that are present in more than 30 of the states, and there are new states where a case law or vehicle-specific regulations carry similar concepts. The practical fact is that the same judgment as to the use of force, when it is justifiable, when it is necessary to retreat, and what is to be considered as proportional, may be made under varying criteria at different places.

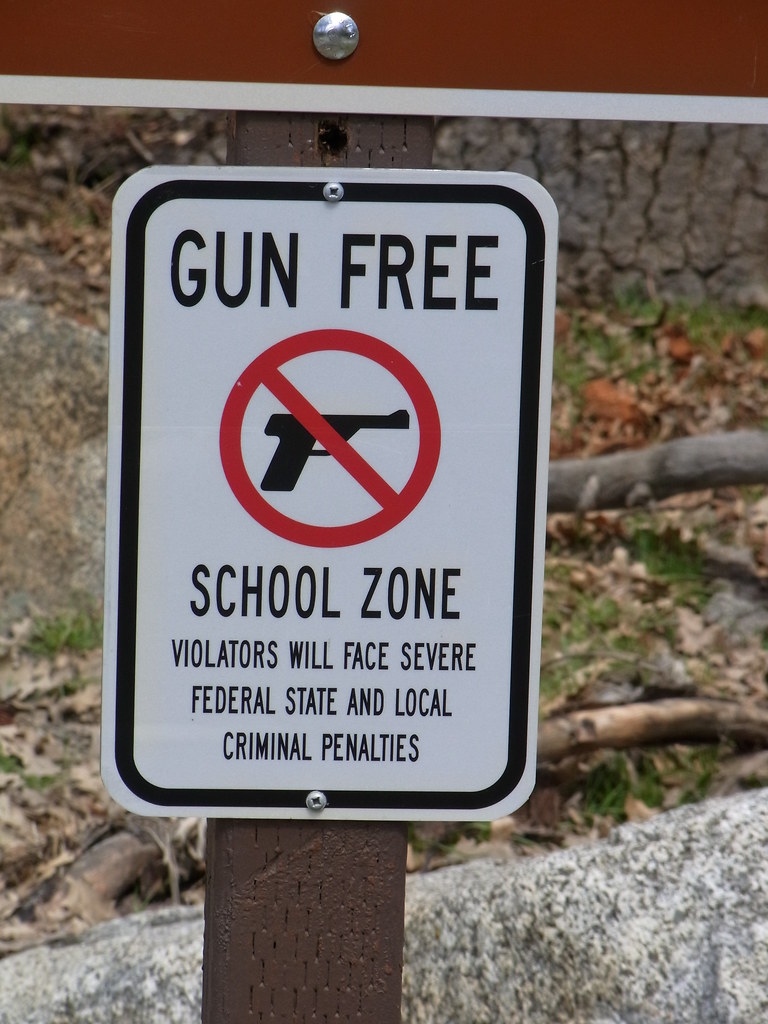

8. Misreading “gun-free” rules in places that are still heavily regulated

One of the quickest methods of the lawful carry turning into the illegal possession is location restrictions. Federal regulations are the only ones that surprise people: firearms are not allowed on postal grounds, such as parking lots, and airports attract clear boundaries on sterile grounds. Another tier is added by schools: the federal Gun-Free School Zones Act has a definition of a school zone: it is a 1000 feet zone around school premises, and this definition may have certain exceptions based on type of permit and state issuance. In addition to government property, there are the privately-owned property policies, and statutes of state-sensitive place, which may modify the front-door rule, and may provide penalties more severe than being asked to go.

The through-line is not carelessness but incongruity. The common habits described as a source of most of the legal disasters in this context are based on the assumption that common practices of traveling, storing, lending, or carrying do not alter their meaning in different jurisdictions and locations. To gun owners who strive to remain law-abiding, marksmanship is not the technical skill. It is acknowledging that the law system takes a firearm as one thing and a controlled condition and that condition can vary quicker than the itinerary of the day.