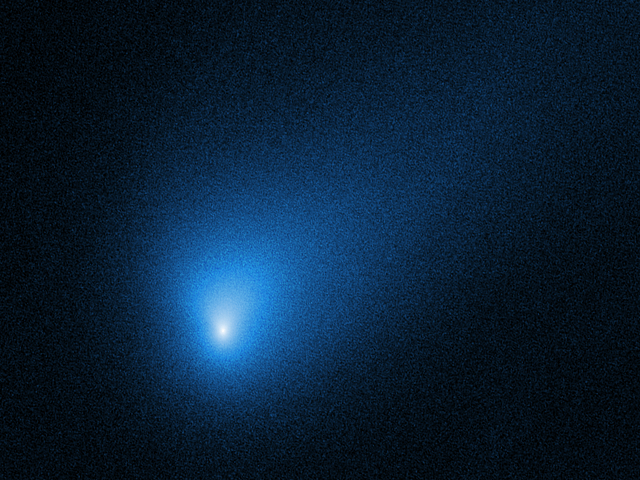

When 3I/ATLAS appeared in survey data the first time, it appeared just like any ordinary point of light, a dim point that was floating along amongst a rich field of stars. In less than twenty-four hours its course gave another tale of its own: the circle was not completed. The object was going through.

That mere geometrical reality made 3I/ATLAS an engineering-grade objective. Having only a few days before it was heading to the interstellar space, teams were relying on distributed observatories, spacecraft that were already in place across the solar system, and the already tested chemistry in laboratories in order to get as much data as possible within the given amount of time.

1. A trajectory too open to belong here

The third known interstellar comet was 3I/ATLAS with its orbit being a hyperbolic- unbound curve that cannot be formed by regular dynamics in the solar system. Its movement was observed to be linked to velocities as great as 250,000km/h, a rate that reduces to a sprint each subsequent campaign. The object reached perihelion on October 30, 2025, approximately 1.4 AU, within the orbit of Mars and was then sent out on a single pass through the neighborhood of the Sun.

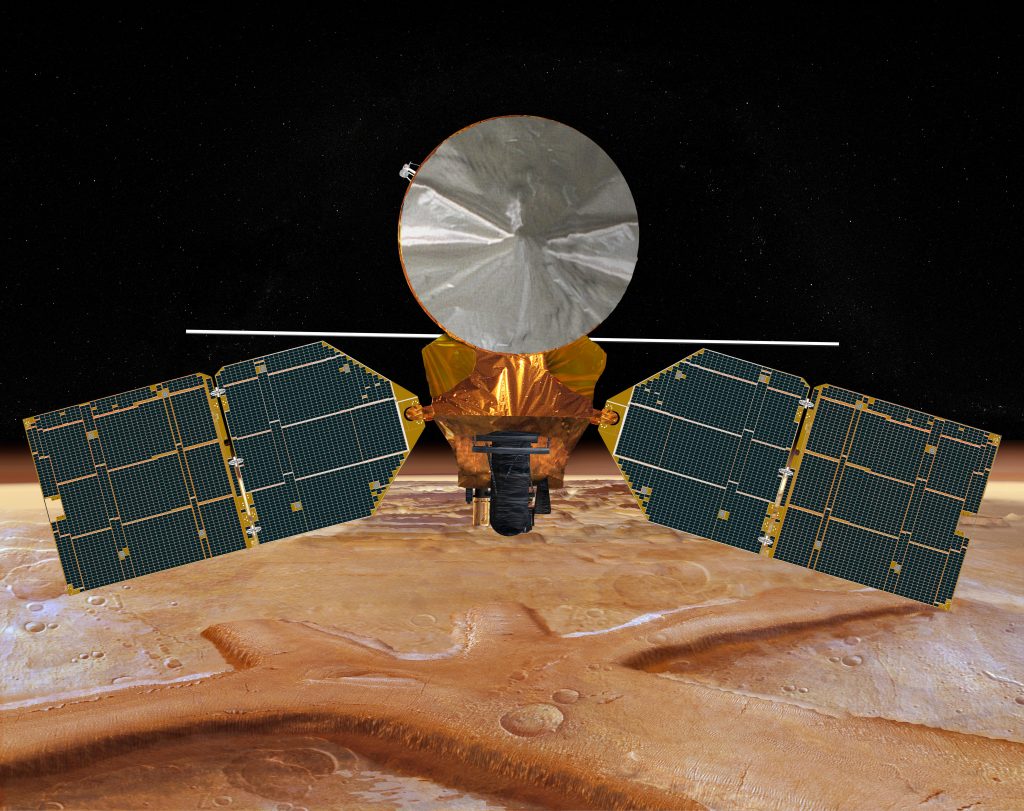

2. Mars-based triangulation that tightened aim by tenfold

Small pointing errors can also waste telescope time when the target is small and faint. One significant advancement was the observation of geometry: ESA was using the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter in Mars orbit to look at the comet using a second baseline, which was merged with astrometry at Earth. The strategy provided a tenfold decrease in positional unpredictability as it took advantage of the observation information gathered by its ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, and the comet came to within 29 million km of Mars at its nearest approach. The attempt also drove the work outside of the ordinary playbooks since the movement of the spacecraft within the circle of Mars was to be estimated accurately when it was required to get the measurements of the stars.

3. Carbon dioxide chemistry that stands out from solar system comets

Spectroscopy transformed the coma into a list of volatile inventory. The enrichment was extreme and was reported: CO2/H2O = 7.6 ± 0.3, attributed to the JWST/NIRSpec and SPHEREx analysis and referred to as being much higher than the normal comet trends. The composition of the coma was also substantial (CO/H2O = 1.65 ± 0.09), and this could not be explained easily using the typical solar system template that is based on water being dominant after the heating of a comet.

4. A cosmic-ray “processed zone” rather than pristine interior

The best update offered by the supportive literature is not necessarily what the gases are, but what that tells us concerning what layers are being sampled. The coma in the same study is considered to occur mainly due to an irradiated outer shell constructed by the galactic cosmic rays, this has been demonstrated by laboratory work which indicates that irradiation can transform CO into CO2 and also form crusts rich in organic matter. It also estimates that the active region of erosion is no more than 1520 m in depth, so observations are likely to be in a long-exposed surface, and not on untouched interior ices. Practically that reformulates interstellar comet science: the earliest available material can be an account of time in the galaxy, not a record of how the galaxy was formed.

5. Nickel without iron and a chemistry door opening

Another anomaly was added by ground-based spectra nickel was observed without the iron that usually accompanies it in comet observations. There is one suggested route through which the highly volatile carrier is used that disperse upon an ultraviolet light, stripping nickel to the coma and aiding in the maintenance of activity long distances away from the Sun. Thomas Puzia wrote that, it opened the door to a whole new world of chemistry that we never had a chance to explore before. This leads to an outcome of less of a single mystery than a poke that interstellar processing and non-standard molecular pathways can take over what is being sensed by instruments.

6. A rehearsal for “use what is already flying” planetary defense

3I/ATLAS was not a danger, but provided some systems experimentation: making measurements of orbit by the use of sensors never intended to monitor small bodies. ESA reported that it was the first ever time that the Minor Planet Center database officially accepted (and received) astrometric measurements of a spacecraft orbiting another planet.

That is operationally important in that future high-uncertainty objects will enjoy the advantage of being able to recruit multiple vantage points very rapidly, although those platforms may be constructed to other primary uses.

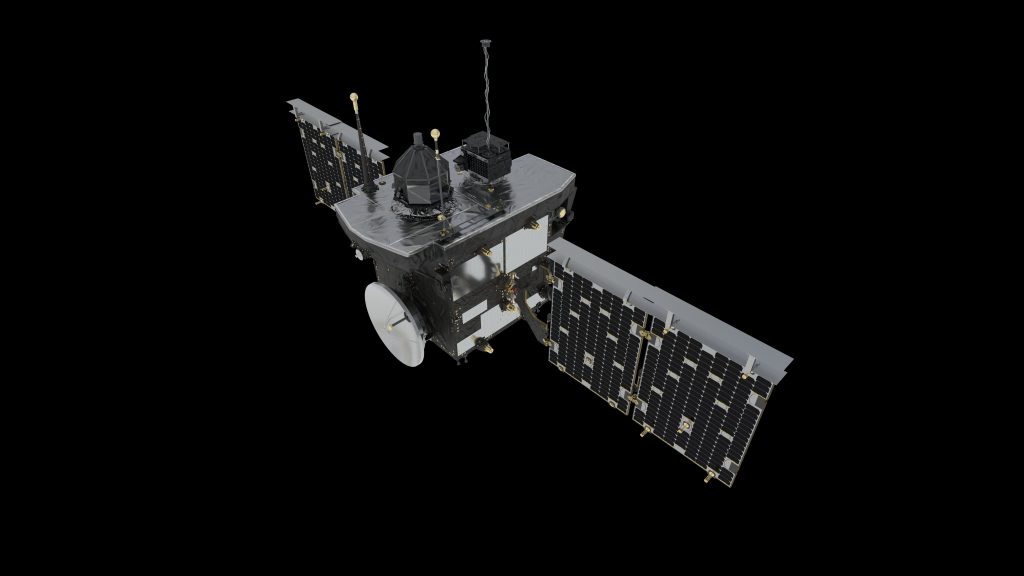

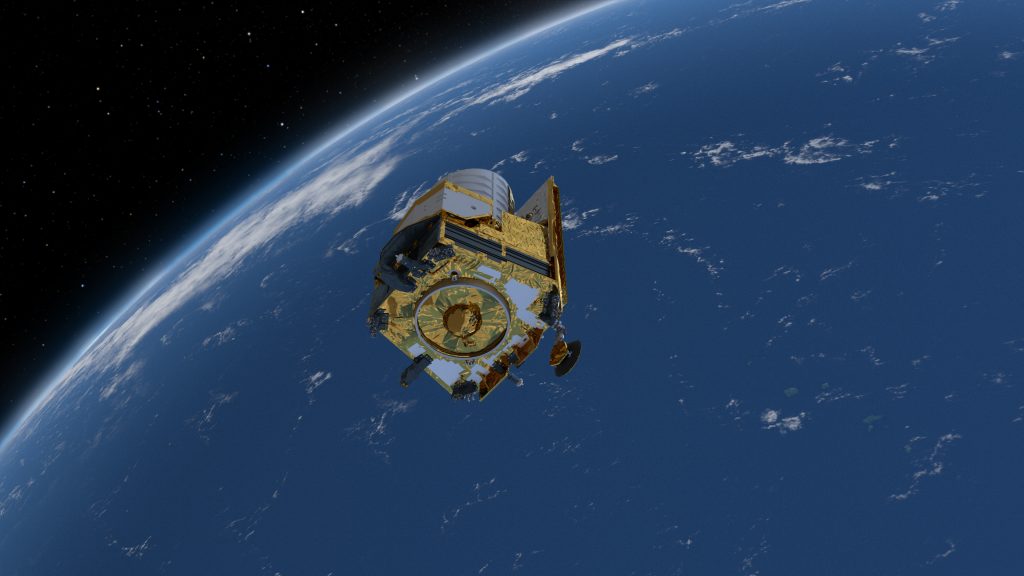

7. Why Comet Interceptor is built for the next short-notice target

The moral of the 3I/ATLAS engineering lesson is cruel: interstellar visitors are not patient. The Comet Interceptor concept presented by ESA will deal with it by placing a mission at the Sun-Earth L2 until a dynamically acceptable new comet is detected after which a flyby with three spacecrafts will be done to record multi-point data and the development of a 3D image of gases, dust, and plasma worlds. The readiness posture of the mission launching without any known target and waiting is consistent with the fact that few objects are found late and go through the inner solar system fast.

3I/ATLAS abandons images and spectral lines. It gives a pattern: accuracy in the work of orbit is greatly increased when the solar system is viewed as a distributed observatory and composition is more and more history on the surface as well as origin. The second interstellar body will not come on time. The more observation geometry, rapid-response mission design, and radiation-informed materials science have grown to maturity, the better will be the science return whenever one more unbound orbit crosses the sky.