Almost 6 meters beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the archeologists have been excavating within an area which currently doubles as a church and at the same time acts like a stacked archive. The floor of the basilica, upon which pilgrims walk, upon which clergy have worshipped, upon which masons have repaired, upon which soil has filled, upon which mulls have covered, upon which edges of walls have been submerged, upon which edges of walls have been found to have been buried, upon which have been found the footprints of plants scarcely big enough to be seen under a microscope, has become the entrance to a more ancient Jerusalem: faces cut limestone, soil fills, buried edges of walls, microscopic traces of vegetation.

What makes a reader with engineering inclinations hesitate to read is not merely what is being discovered, but how a building functioning as a sacred (as opposed to a museum) building can be examined without interfering with the life that commendation. It has been divided into several zones such that parts can be opened, excavated, documented, then covered once again as the worship is going on. The focal point of the effort is a unique combination of conservation, archaeology, and building systems work, including flooring, drainage, and utilities, combined with the three communities that control the church jointly.

1. A cultivated garden appears where stone once ruled

Some of the most dramatic findings are the minute relics: olive pits, grape seeds and pollen. In the spot below the floor of the basilica, the presence of olive and grapevine has been confirmed, and this confirms the existence of cultivated plots even before the church was constructed. The discovery recalls the story in the Gospel of a garden nearby the place of crucifixion and burial, and the passage: Now there was a garden where he had been crucified, and in the garden there was a new tomb where no one had yet been laid. Francesca Romana Stasolla, head of the excavation, made the case that the plant evidence was particularly interesting to her, given what was said in the Gospel of John, its information being viewed as being written or gathered by someone who knew Jerusalem better than anyone else, including her: “The archaeobotanical evidence was of particular interest to us, in light of what we have read in the Gospel of John, information that is attributed to the author as having been written or gathered by someone who was acquainted better with Jerusalem than anyone of us.

2. Archaeobotany turns dust into landscape

Seeds and pollen are not used to decorate an excavation; they serve as metrics. Researchers can differentiate between dumped fill, the living soil, cultivated ground and disturbed sediment by monitoring plant remains within particular layers and older and later surfaces by leveling. The botanical traces have provided a move towards an industrial extraction to working land in the Holy Sepulchre, providing a material ground why a quarry might become a gardened margin beyond the city. This method is gradual, cautious, and mechanical–precisely due to the fact that the evidence is minute. Nevertheless its compensation is uncharacteristic intelligibility: landscape recreated not through murals or subsequent narratives, but through that which survives in the ground.

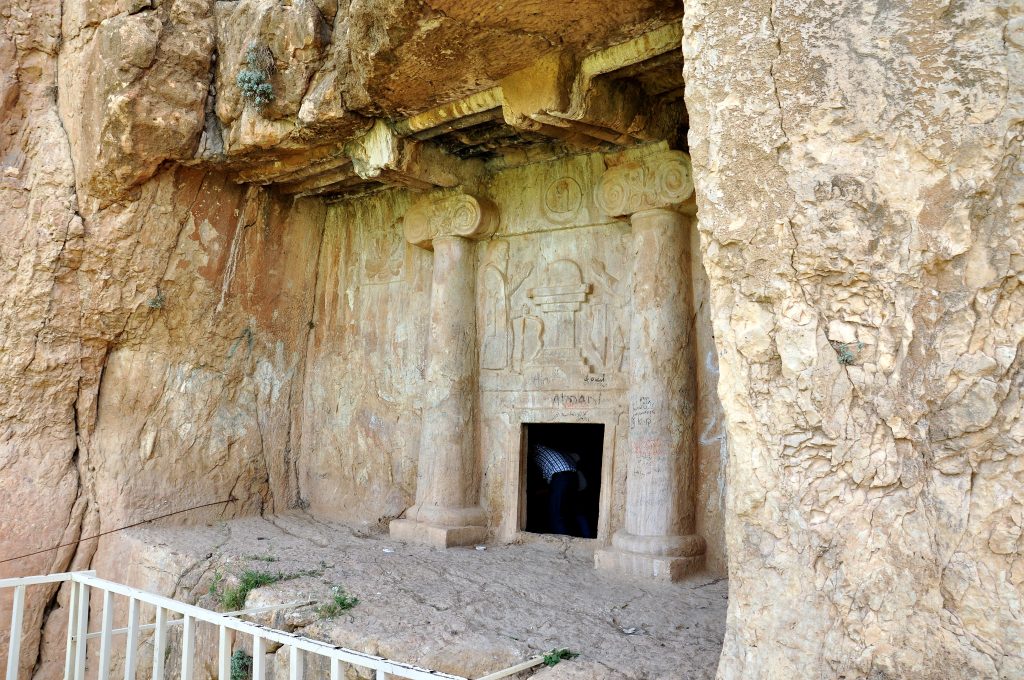

3. The site began as an Iron Age limestone quarry

Prior to its being sacred space, it was construction space. Archeologists recognize the site as an Iron Age quarry where limestone was carved out and taken away. Stasolla explained that that industrial geometry was important in the future, in the opinion of Stasolla, when we need to imagine that, as the quarry was increasingly abandoned, the tombs were cut at various levels. That mere discovery of engineering, the stepped extraction surfaces and the irregular underlying rock, is one of the reasons to understand why subsequent constructors had a challenging task with the base. The original archaeological architecture of the site was subtraction, and all that followed had to deal with those excavations.

4. Tombs followed the quarry, before any church existed

With the loosening of quarrying, rock-cut tombs favored in the same area, which is again in line with the burial practice beyond city boundaries. The area has been found in excavations to have several tombs including one that is traditionally linked to Joseph of Arimathea. The structural issue is that burial chambers, carved holes and reused holes formed a complex subsurface, which would then be covered, stabilized, rerouted or included as the footprint of the church developed. It serves to remind that bedrock does not necessarily imply solid; in urban areas of ancient times, it can also mean rock that has been hollowed, re-used and re-bridged by subsequent floors.

5. Early builders solved uneven ground with fill and leveling

With the Christian construction prevailing in the fourth century, the landscape had to be rendered habitable. Excavation has demonstrated that sloping quarry surfaces were dealt with by means of the addition of soil and ceramic-filled fills to smooth the area- an early practical method, which has the air of a field explanation to a large scale grade issue. Later stages produced walls and foundations which may be followed as choices: where loads were transferred, where edges strengthened and where old cuts hindered new designs. That concealed ground-work is the silent precondition of all that is above: columns, pavements, thresholds, and ritual paths in one of the basilicas still in existence, centuries after its continued repair.

6. Coins, steps, and the engineering of pilgrimage flow

Marble steps and a coin hoard found in front of the edicule with the latest coins struck during the reign of Emperor Valens (364378) provide a narrower date of an early Christian period of the edicule development. Stasolla explained a sudden near sequencing of developments: we could record a period of monumentalization at the onset of the fourth century and a second period at the close of the fourth century. Those changes, the steps minimized with an increase in floor height, are like a reply to design use; the management of approach, the flow of crowds, and the re-establishment of the spatial accent of the shrine. The edicule was not just a place of worship, but one structured to be visited.

7. A functioning church is being excavated like a living building site

This dig, unlike most of the others, must co-exist with liturgy. Labor goes on in shifts and between bouts of great feast days, and flooring can be laid out temporarily, and closed in, to allow circulation. Stasolla described the process as using a metaphor of a builder: although we cannot see the whole church dug out in a glance, new technologies are enabling us to rebuild the larger picture in our laboratories. That bigger picture is becoming more digital: recorded layers, photographed surfaces, cataloged fragments and reconstructions which allow researchers to examine the entire but only physically open a piece at a time.

8. Cooperation is a project requirement, not a footnote

The restoration and excavation have moved forward because the Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, and Latin Catholic communities agreed to coordinate access and decision-making. One statement distilled the dependency plainly: “Without this cooperation and unity, the project in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre could never have been realized.” The work includes not only archaeological teams but also infrastructure planning floor replacement, utilities, and building safeguards where scheduling and permissions are as critical as tools.

In a site shaped by repeated restoration, present-day coordination becomes another layer of the building’s history: a modern system added to protect an ancient one. Under the Holy Sepulchre, the most enduring surprise is how ordinary processes quarrying, gardening, leveling, drainage, foot traffic accumulate into sacred architecture. The evidence does not sit in a museum; it sits beneath a working floor. In that sense, the excavation reveals a continuity as much as an origin: a place repeatedly rebuilt so people can keep arriving, step by step, onto the same ground.