“For most of the Space Age, the search for intelligence beyond Earth leaned on a narrow premise: if someone is out there, they might talk on radio. That expectation has started to loosen not because of a single decisive discovery, but because astronomy now generates the kind of data that can test stranger possibilities.

Two threads dominate the current moment. One looks for energy use on a stellar scale, where engineering could advertise itself as heat. The other inspects exoplanet atmospheres for chemistry that might be difficult to sustain without biology. Together, they turn an old question into a more tractable one: not “Who is calling us?” but “What would advanced activity look like in photons?”

1. Infrared “waste heat” as a technosignature

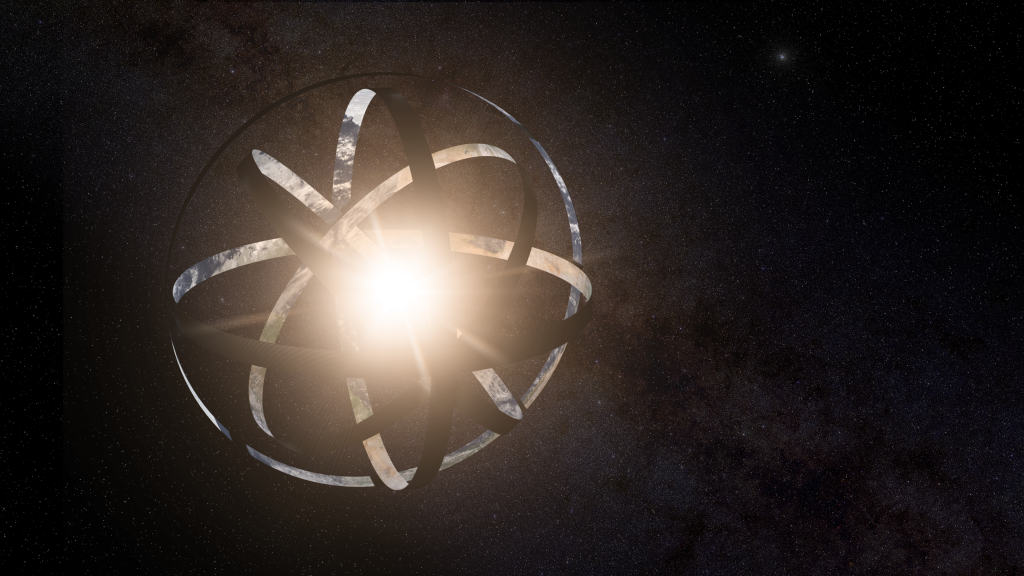

Large sky surveys have identified stars with mid-infrared emission far above what stellar physics predicts, a pattern consistent with energy capture followed by re-radiation as heat. In one prominent set of candidates, anomalous infrared (heat) signatures are treated as potential hints of Dyson-like structures rather than messages. The underlying idea is old Freeman Dyson’s 1960 suggestion that a civilization could surround a star with collectors but modern catalogs allow systematic screening rather than one-off curiosities.

2. Why dust and galaxies keep impersonating megastructures

Infrared excess is common in nature. Protoplanetary disks, debris from collisions, and background galaxies can all add heat-like glow in the same bands used to hunt technosignatures. The engineering challenge is therefore methodological: pipelines must eliminate look-alikes across millions of sources, using imaging checks and statistical filters that can spot contamination. The remaining candidates matter less as “proof” than as test beds for follow-up, where spectroscopy and higher-resolution imaging can decide whether the light comes from dusty astrophysics or something harder to classify.

3. K2-18 b and the moving target called a biosignature

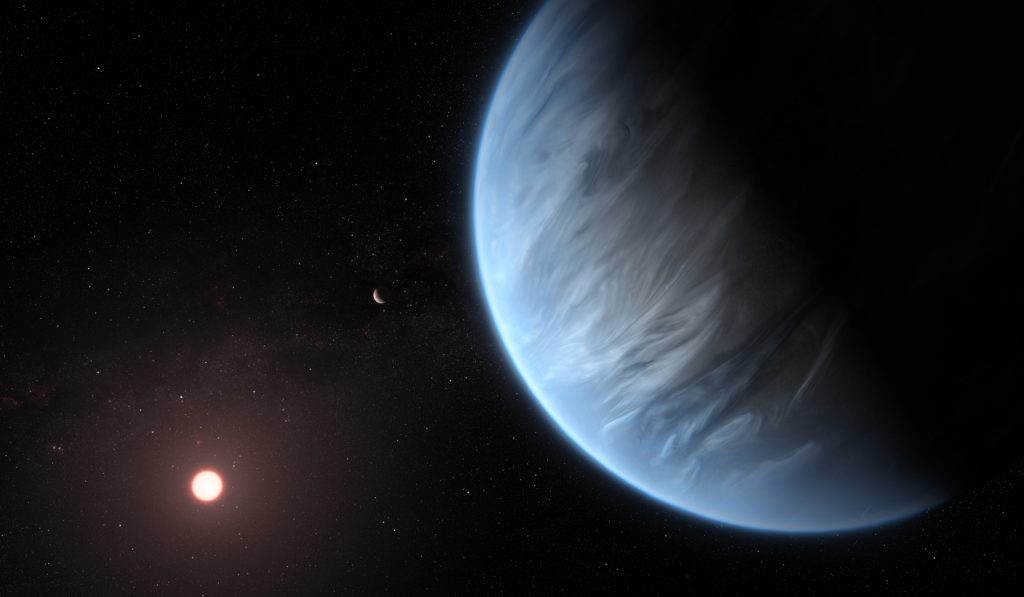

K2-18 b sits about 124 light-years away and has become a proving ground for atmospheric inference. JWST spectra show methane and carbon dioxide, and earlier analyses argued for dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a molecule associated on Earth with marine life. A later NASA-led reanalysis strengthened the broader atmospheric picture but reduced the DMS case to a tentative signal; the study reported about 2.7 sigma confidence for DMS, below the field’s standard for a firm detection, as described in a NASA-led analysis uploaded to the arXiv. The result reframes the headline question from “Is this life?” to “How does one keep from mistaking model choices for molecules?”

4. Context-first spectroscopy: molecules rarely travel alone

Exoplanet atmospheres do not offer single-compound verdicts. Instruments infer gases by subtracting starlight filtered through a planet’s limb, then matching absorption features against competing chemical inventories. The hard part is degeneracy: DMS can be confused with chemically related species, and trace signals can drift when analysts assume different temperature profiles or haze properties. The practical implication is that future campaigns must seek ensembles companion gases and self-consistent chemical networks rather than celebrate isolated peaks.

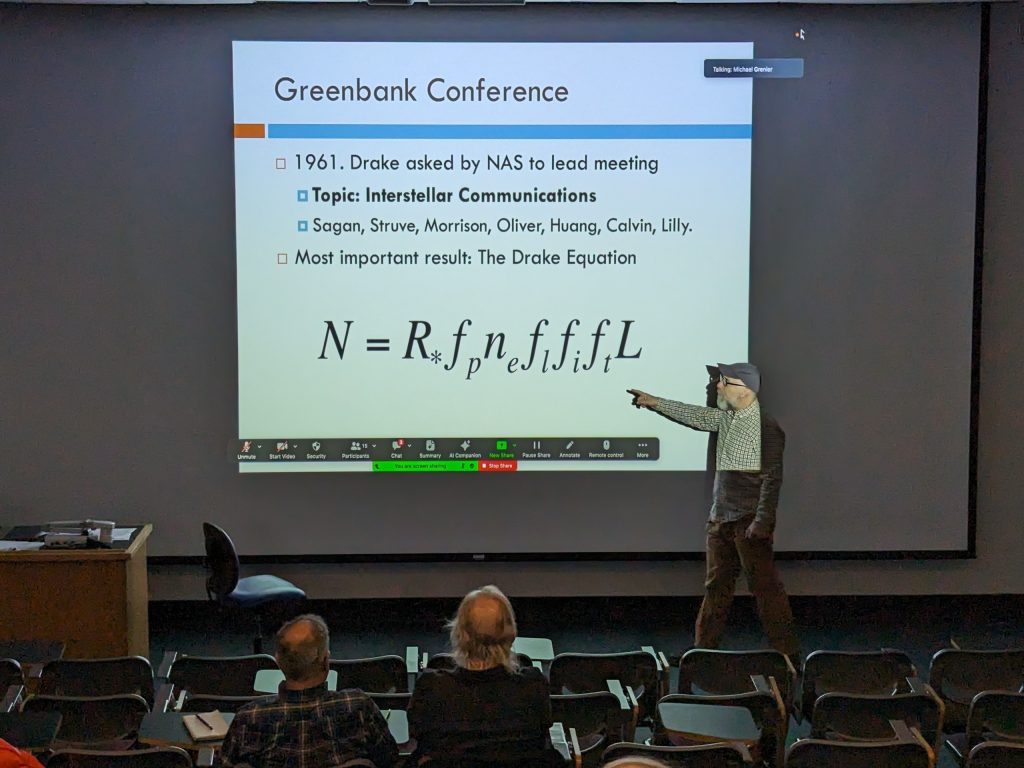

5. The “cosmic archaeology” reframing of the Drake equation

Instead of asking how many civilizations exist now, some researchers emphasize how often technological species could have emerged across cosmic history. Using exoplanet statistics, this approach produces a pessimism threshold: humanity remains unique only if the probability of civilization arising on a habitable world is extraordinarily tiny. In a widely cited calculation, another technological species likely arose in the Milky Way if the odds are better than one chance in 60 billion per habitable planet. The number does not guarantee neighbors; it changes what “rare” must mean if nobody else ever happened.

6. The zoo hypothesis as a constraint, not a punchline

Fermi’s “Where is everybody?” persists because modern astronomy has expanded the inventory of potentially habitable worlds without producing definitive technosignatures. One rigorous response is the “zoo hypothesis,” coined in 1973 by John A. Ball, which holds that advanced civilizations might deliberately avoid obvious contact.

A recent analysis in Nature Astronomy argues that, given the silence, the space of explanations narrows toward either extreme rarity or deliberate nonappearance. Either way, it pressures SETI to diversify what “evidence” could look like.

7. Why the next step is verification, not more excitement

What links infrared anomalies and debated biosignatures is not sensationalism but a maturing workflow: candidates emerge from big data, then survive only through repeated, instrument-diverse tests. Direct imaging and sharper infrared telescopes could rule out dusty mimics around technosignature candidates. On the biosignature side, dedicated future observatories designed for life-detection spectroscopy could reduce today’s model-dependence and push tentative molecules into either confirmation or dismissal.

None of these clues, on its own, establishes another civilization or even another biology. Their collective value is operational: they define where astronomy can now place tight, testable limits on phenomena that used to live mostly in speculation. In practice, the search is converging on a simple engineering principle: advanced activity, if it exists, must leave accounting traces in energy and chemistry. The instruments are finally becoming capable of auditing those ledgers.”