Interstellar objects arrive without reservation, crossing instrument fields of view that were designed for planets, moons, and the near sky. When comet 3I/ATLAS moved through a geometry that placed it near the Sun from Earth’s line of sight, a narrow observational window opened elsewhere: Mars.

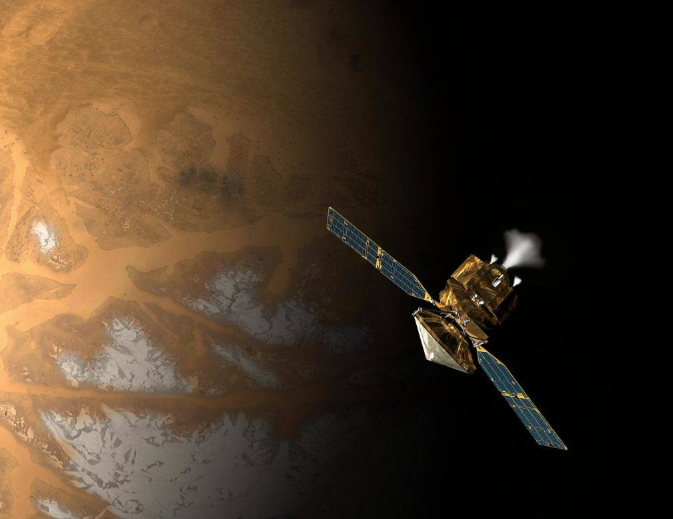

In early October 2025, three NASA Mars assets Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, MAVEN, and the Perseverance rover aimed at the comet during a passage that brought it to roughly 30 million kilometers from Mars, enabling the closest spacecraft vantage NASA was expected to achieve for this visitor.

1. A planetary camera repurposed for deep-space tracking

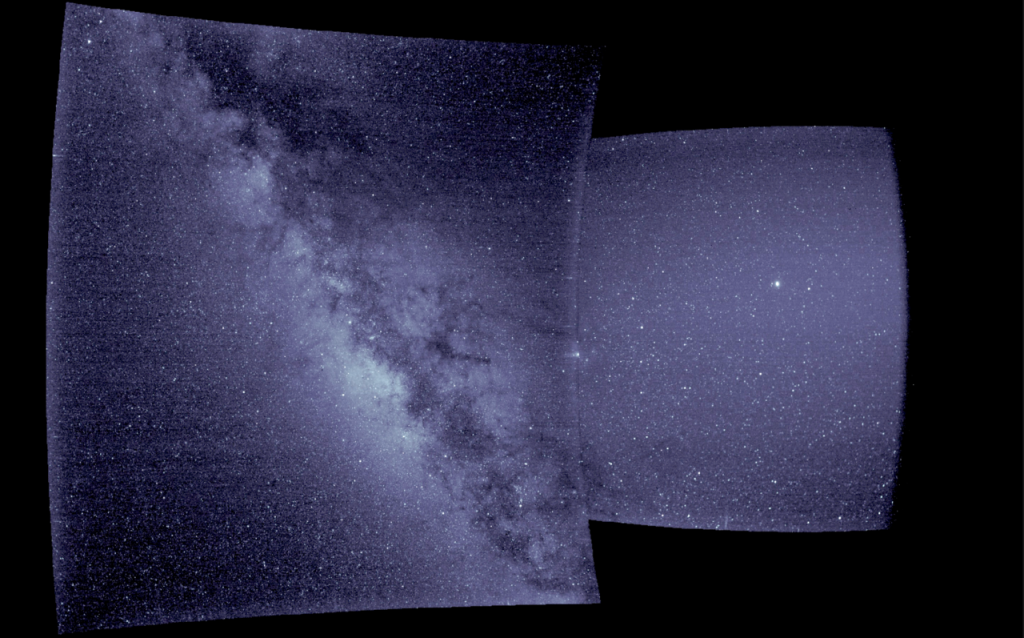

MRO’s HiRISE camera is celebrated for mapping Mars at fine scales, but the 3I/ATLAS campaign demanded a different skill: tracking a faint target against a star field while the spacecraft rotates to follow the comet’s motion. The observation required careful pointing to limit interference from Mars’ thin atmosphere and stray sunlight, echoing the technique used during the 2014 comet Siding Spring campaign.

The resulting frames resolved the comet at about 30 kilometers per pixel, a scale suited to measuring the overall structure of a coma rather than the nucleus itself. Shane Byrne, HiRISE principal investigator, said, “Observations of interstellar objects are still rare enough that we learn something new on every occasion.”

2. A coma measured in thousands of kilometers, not guesses

HiRISE imagery indicated a diffuse coma roughly 1,500 kilometers across, turning an otherwise ambiguous smudge into a measurable physical system. That size scale supports follow-on work: estimating dust production, comparing brightness profiles, and testing whether jets might be detectable as asymmetries on the sunward side. The payoff is less about a pretty picture and more about turning geometry and photons into constrained parameters.

3. Ultraviolet fingerprints from a Mars orbiter built for atmosphere science

MAVEN’s Imaging Ultraviolet Spectrograph extended the campaign into ultraviolet wavelengths, where emissions from hydrogen, hydroxyl, carbon, and oxygen can be isolated. Over a ten-day run, IUVS observations supported chemical “tagging” of volatiles in the coma and helped derive an upper limit for the comet’s deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratio. Because D/H varies across solar system reservoirs, the measurement framework provides a consistent way to compare an interstellar comet’s water history to known comet populations.

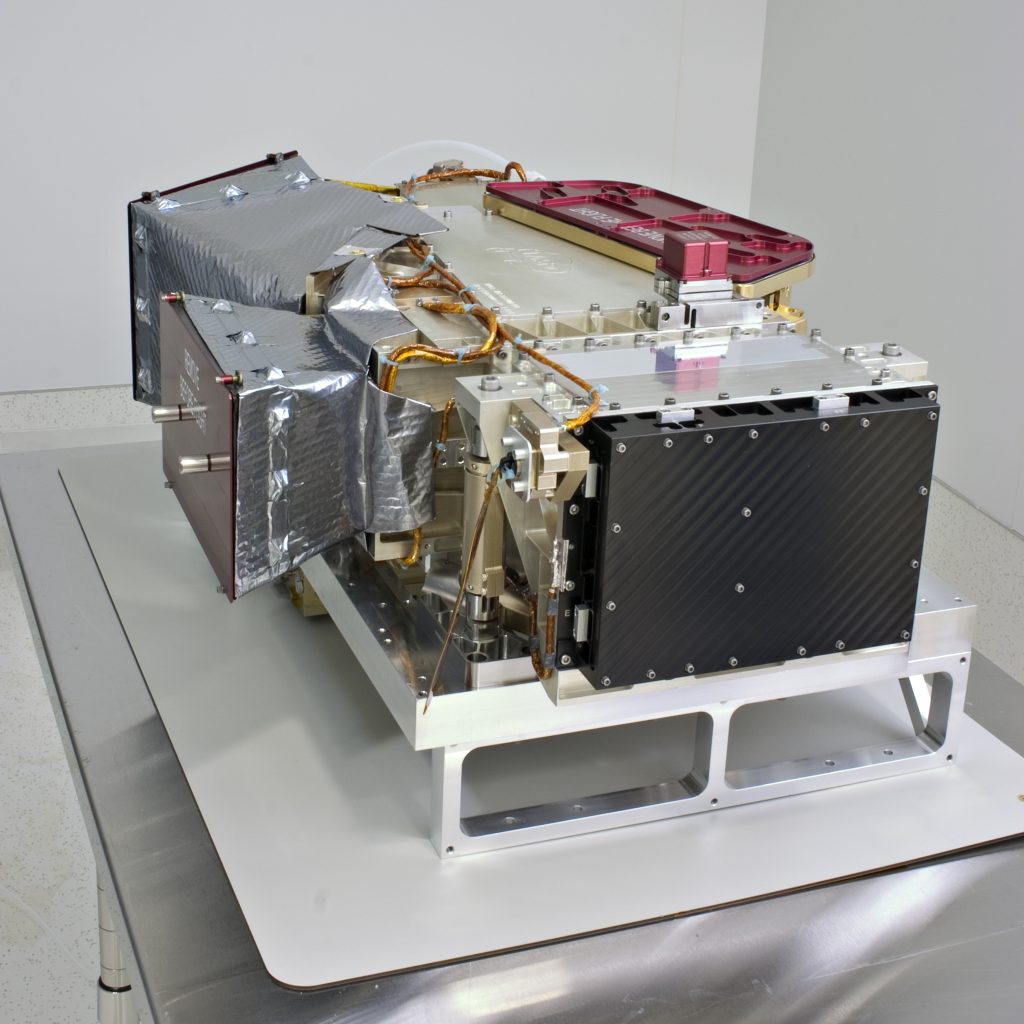

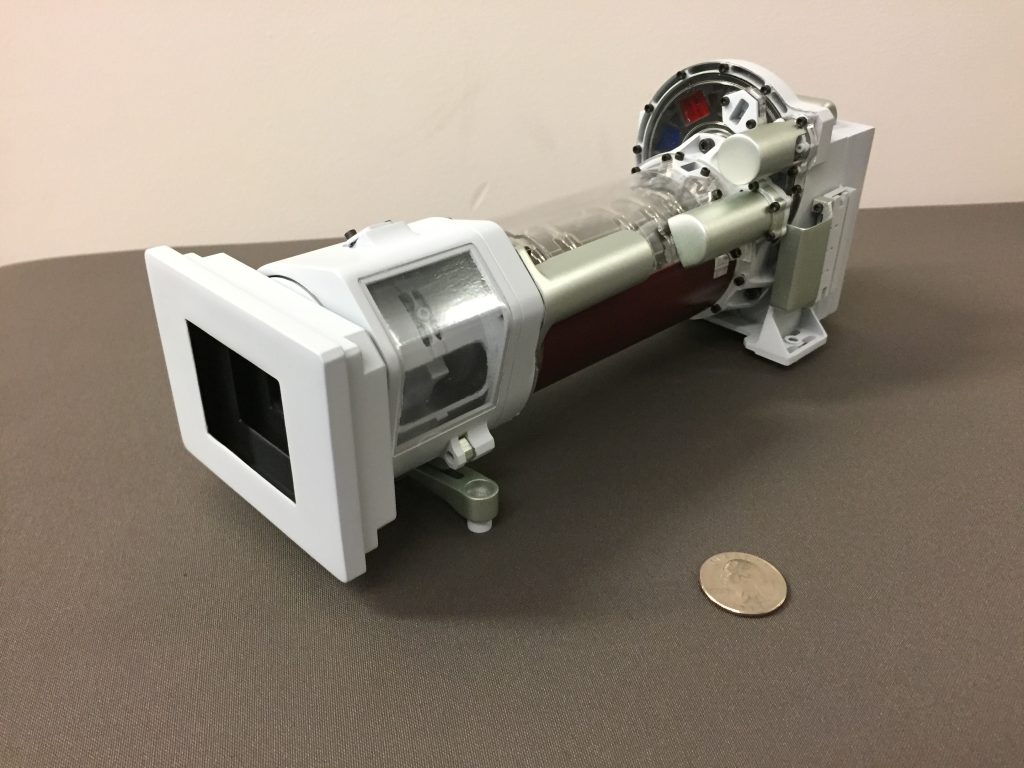

4. The hardest image: a dim target from a rover that cannot track

Perseverance added the rarest viewpoint an observing station on another world’s surface but with strict limits. Mastcam-Z is not mounted on a gimbaled astronomical tracker, so long exposures produce star trails while a fast-moving, faint comet struggles to register. The result 3I/ATLAS as a dim point amid trails documents the challenge as much as the target, and it validates methods for future transient-sky attempts from fixed planetary platforms.

5. Multi-instrument coordination that behaves like a single observatory

Optical frames from HiRISE, ultraviolet maps from IUVS, and surface imagery from Mastcam-Z formed a dataset spanning different wavelengths and observing conditions. The value of this assembly lies in cross-checks: dust morphology in visible light can be compared with gas distributions traced in ultraviolet, tightening interpretation of activity drivers. The approach aligns with previous comet encounters that combine remote sensing modes to separate dust behavior from volatile release.

6. Observing through the Sun-gap with help from heliophysics tools

Earth-based telescopes lost access when the comet moved too near the Sun in the sky, but spacecraft built to watch the near-Sun environment continued collecting. The campaign expanded into a broader fleet, including missions that can image close to the solar glare. Reference tracking included images from STEREO and observations from SOHO, while Parker Solar Probe recorded the comet with WISPR during a period when final calibration and stray-light removal were still required for clean interpretation.

7. Interstellar confirmation depends on precision, not appearance

Labeling 3I/ATLAS as interstellar is anchored in astrometry: the orbit is hyperbolic, meaning it is not bound to the Sun. The object was first identified by the NASA-funded ATLAS survey in Chile, then followed by major space observatories, with Mars-based views filling a key geometry gap. NASA’s own overview notes the comet’s closest approach to Earth remained distant at about 1.8 astronomical units, underscoring that the scientific leverage came from viewpoint and instrumentation, not proximity to Earth.

Only a few interstellar objects have been confirmed to date, so each one becomes a systems test: instruments, pointing, calibration, and cross-mission planning operating at the edge of intended design.

For Modern Engineering Marvels readers, the enduring story is the method turning Mars orbiters and a rover into a coordinated observatory so that a brief, faint passage still yields measurements that can be compared, archived, and revisited as analysis matures.