Only three interstellar objects have been confirmed as passing through the Solar System, and comet 3I/ATLAS is the first to arrive with the familiar toolkit of a comet: an icy nucleus, a living coma, and changing jets.

A new set of eight spacecraft images turns that rarity into something interpretable. Value is not just sharpness; it is coverage multiple instruments, multiple geometries, and multiple wavelength bands assembled into a portrait that can be read for motion, structure, and chemistry.

The result also serves as a reminder: space imagery is not a single “snapshot.” It is measurement, calibration, stacking, and choices about contrast and color that turn photons into a usable map of an object no one can visit on demand.

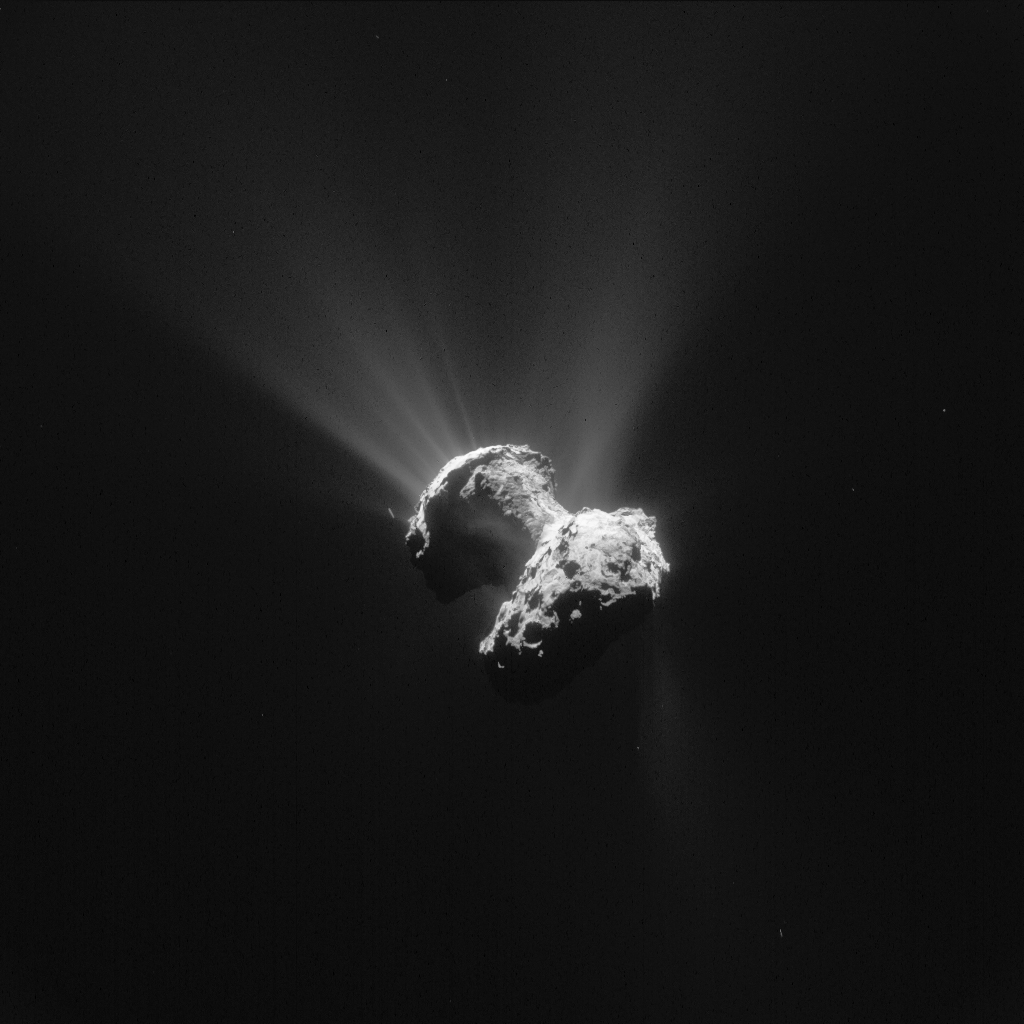

1. A nucleus that finally looks like a surface and not a smudge

Interstellar comets typically pop into the public imagination as bright points with fuzzy halos. In these eight frames, 3I/ATLAS presents an object with edges, shadowed topography, and an irregular outline that supports engineering-grade questions: where are the active regions, how does rotation change illumination, and how stable is the near-surface layer that feeds the coma?

That sort of optical clarity is important, because it separates “brightness” from “structure.” A tight, bright center may be the nucleus or a near-nucleus concentration of dust, depending upon exposure strategy and processing. In this case, these multiple views make it easier to sort out persistent features versus transient outflow. The most valuable takeaway is simple: the nucleus is not a tidy sphere, and the coma does not expand as a consistent cloud.

2. Jets that turn on and off between frames

This comet exhibits coma morphology across a short sequence consistent with localized venting. Where jets are seen to appear and disappear between images, this can be diagnostic of the activity not being uniformly distributed, and the comet takes on a character of a body containing discrete pockets of volatile material rather than a uniformly sublimating surface.

That interpretive leap becomes stronger when images are time-sliced rather than treated as single hero shots. A changing jet is a mechanical clue – an interaction between rotation, sunlight, and the thermal properties of the nearsurface layer. Even without a close flyby, repeated imaging can constrain where activity is concentrated and how quickly it evolves.

3. A rotation rate measured from brightness, not guesswork

Ground-based photometry adds a second “sensor” to the image story: time. A published observing campaign found a spin period of 16.16 ± 0.01 hours based on light-curve analysis, with a brightness variation of roughly 0.3 magnitudes, helping connect what appears in images to how the body turns and presents different facets to the Sun.

This is where a still image becomes an operational model. Rotation informs how jets can repeat, how illumination migrates across the nucleus, and how observers schedule exposures in order to avoid smearing on a fast-moving target. It also makes comparisons possible: 3I/ATLAS rotates in a range that does not look exotic relative to active comets native to this Solar System.

4. Chemistry that looks familiar until it does not

Interstellar origin does not automatically mean “alien” chemistry in every band. The optical reflectance data described a slightly red spectrum in the 0.4–0.7 µm range, consistent with organic-rich surfaces often associated with outer Solar System bodies.

Meanwhile, infrared observations revealed an extreme imbalance in volatiles: JWST data showed a ratio of CO₂ to H₂O of about 8:1, among the highest ever seen in any comet. The engineering relevance is practical as well as scientific: different dominant volatiles change how activity initiates with solar distance, how gas drives dust, and what kinds of coma structures are likely to appear under similar illumination.

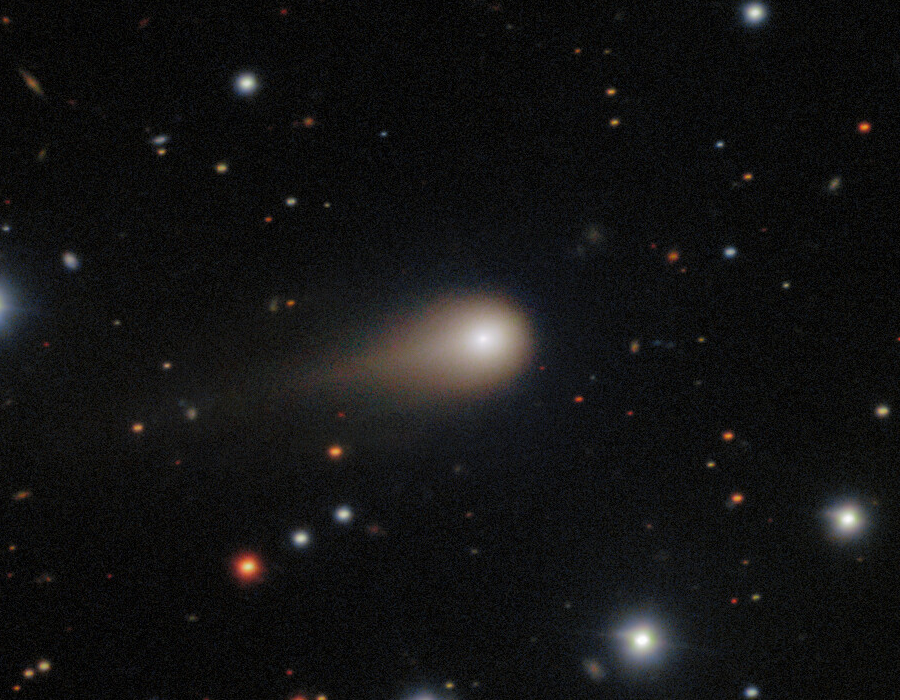

5. A dusty coma that acts like a materials test

One surprising observation note is that the comet showed no obvious visible tail during parts of the monitoring period, along with an asymmetric coma. That combination has been linked to the fact that relatively large dust grains may be staying near the nucleus rather than being pushed into a long, high-contrast tail by radiation pressure.

In other words, the coma may act like an uncontrolled wind tunnel experiment. Grain size, gas production, and viewing geometry all constrain what a camera detects. It is still useful to observe an asymmetric coma with no bright tail: such a view limits the possible dust population and helps normalize what “activity” should appear as for an interstellar body in these conditions.

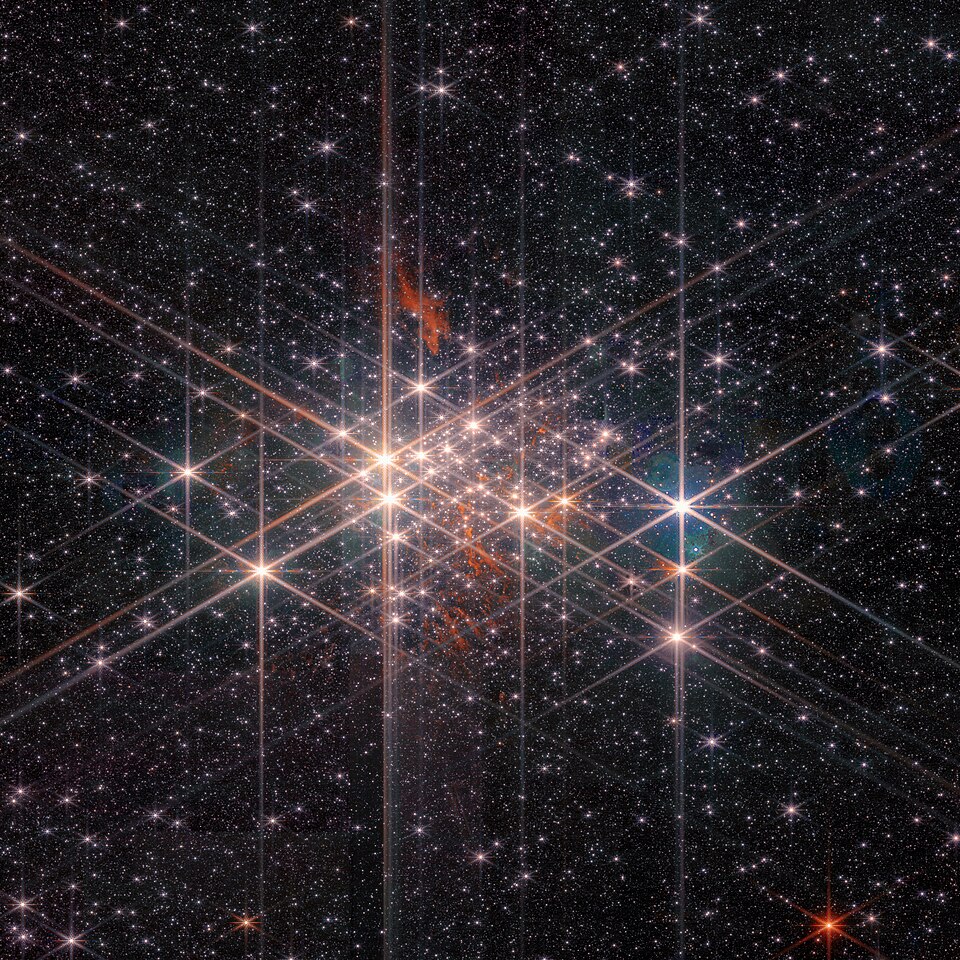

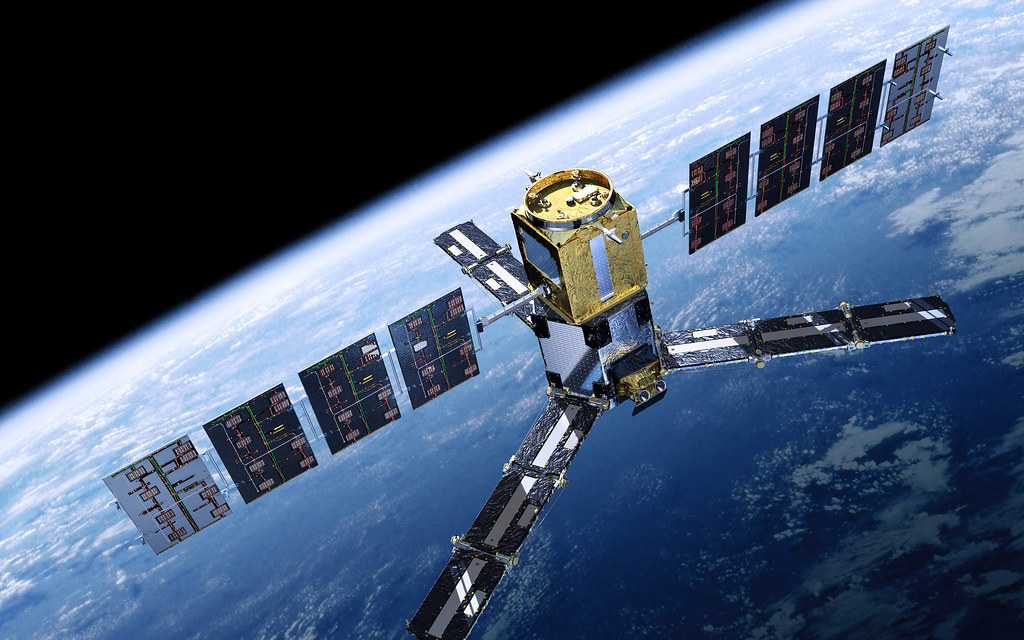

6. A Solar System turned into a distributed camera rig

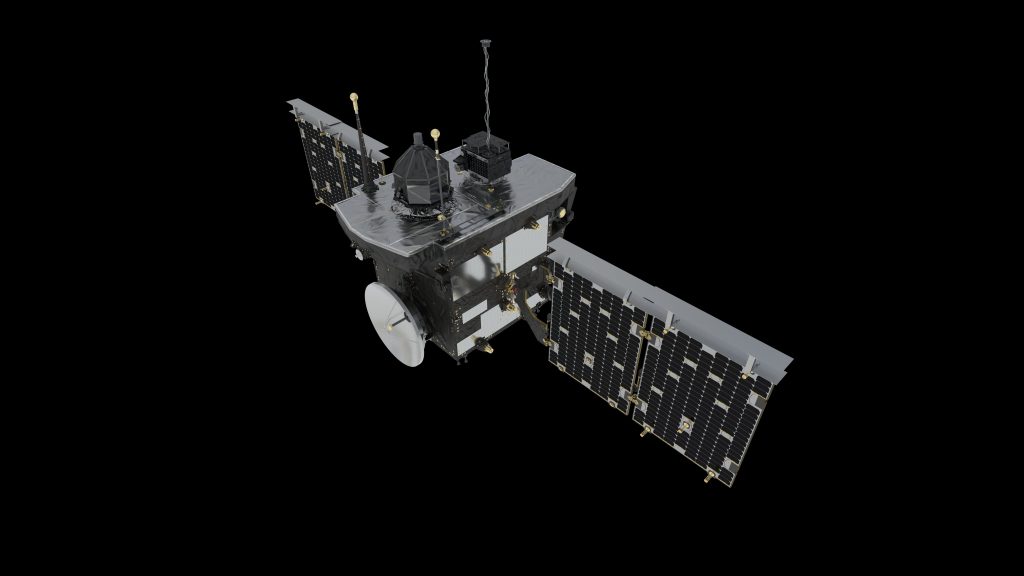

What makes this eight-image set more than a curiosity is the way it was assembled. NASA described a campaign in which twelve assets across the Solar System contributed observations, including spacecraft near Mars, and heliophysics missions capable of watching regions of sky close to the Sun when ground-based telescopes could not.

That approach reflects a mature operational pattern: treat an interstellar visitor as a time-critical target, coordinate instruments that were built for other jobs, and use multi-vantage coverage to reduce ambiguity. Mars assets provided some of the closest looks; heliophysics observers filled in intervals when geometry blocked Earth-based viewing; deep-space spacecraft added longbaseline tracking that improves trajectory refinement.

7. How to read the images without being tricked by “pretty” processing

Interpreting spacecraft comet imagery benefits from the same habits used in Earth remote sensing: identify the scale, look for patterns and texture, and treat color as a legend rather than decoration. NASA Earth science guidance emphasizes that satellite images are measurements combined into maps, not simple photographs, and that false color can reveal materials and motion invisible to the eye. The most practical approach is procedural. Find the most compact bright region that marks the location of the nucleus. Trace the coma, noting whether it is symmetric; asymmetry often indicates a directed outflow or a viewing geometry that favors one side.

Note the direction of the tail in relation to the Sun’s position in the frame; comet tails generally point away from the Sun, not “behind” the comet along its trajectory. When color mapping was used, it encoded wavelength choices, so different hues can separate dust-rich regions from gas-rich regions even when brightness appears similar in a single band. As one mission scientist said: “The scary part is realizing how many we must have missed before we had eyes sharp enough to notice.” With 3I/ATLAS, the eight images act less like a postcard and more like a field manual on how to capture, cross-check, and interpret a fast, one-time target when a new object crosses the Solar System and does not offer a second pass.