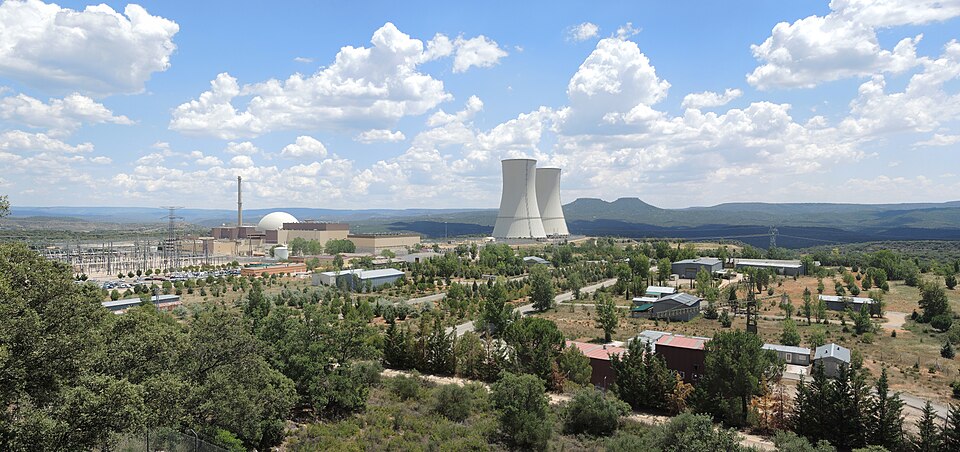

The rapid rise of artificial intelligence has killed the traditional thinking of the demand of electricity. By 2024, U.S. data centers had used 183 terawatt-hours (TWh) of power or more than 4% of the total equivalent in the country that would meet the annual Pakistan demand. According to projections by the International Energy Agency, this will grow by 133 percent by 2030 as hyperscale AI facilities will require as much power in a year as 100 000 households and the largest facility under construction will require 20 times that amount. Such an influx is pushing nuclear energy which has long been viewed as a sluggish, capital-intensive industry, into the spotlight of energy planning.

1. AI and the Energy Appetite of Jevons Paradox.

Efficiency improvements in semiconductor design had long been used to cover up increasing workloads. The computational intensity of AI has already caused a Jevons Paradox in the here and now: as computers become more efficient they are used to run larger and larger models, increasing the net energy consumption. Hyperscale AI data centers, which are typically more than 1 million square feet, have 99.999% uptime and require baseload power unattainable by intermittent renewables. The demand of power in the data centers of Goldman Sachs Research is projected to increase over 160 percent in 2030 with nuclear being the most preferred choice of power source since it is low carbon baseload.

2. AI Structural Impact on Nuclear Planning.

A survey of more than 600 international investors discovered that 63 percent of them consider AI electricity demand as a structural stimulus of nuclear growth. This is no short-lived spike, it is a long-lasting change in load patterns. According to S&P Global Energy, data center usage may hit 2,200 TWh worldwide, a level that challenges the ability of utilities to consider capacity planning differently. Hyperscalers are acting back by entering into decades-long nuclear power purchase agreements (PPAs) and ensuring clean baseload supply at the expense of imposing the cost of grid upgrades, transformers, copper lines, substations, on the population.

3. Two-Speed Market and Supply Shortage of Uranium.

Extracted uranium will be insufficient to satisfy the reactor requirements in the future by less than 75% of the demand. The market was left dependent on the secondary supply of dismantled warheads and stockpiles since 2011, and these sources are almost depleted. By 2026, investors project prices of between $100 and 120/lb, with some projecting to $135/lb -prices used not as growth incentives but as desperation bids to open bit of a mothballed mine and a decade-long permit approval process. The front end of the uranium fuel cycle mining, milling, conversion, enrichment, etc. cannot keep up with the AI demand curve.

4. Designing Bottlenecks in the Fuel Cycle.

Uranium is in the process of acute constraint: the shortage of sulfuric acid in Kazakhstan, shortage of labor after a generation of engineers left the industry, and enrichment capacity in the West was already at full capacity. With the yellowcake on hand, it is still bottlenecked by inadequate facilities in the U.S., France, Canada, and the UK to convert it into uranium hexafluoride (UF6) and reduce it to low-enriched uranium (LEU). Enrichment: U-235 content of 0.7 percent should be raised to 3.55 percent: This would demand an expensive centrifuge plant that would be closely managed by non-proliferation regulations, and would not be easily able to scale up rapidly.

5. Geopolitical Tension in the Midstream Processing.

Approximately 20 percent of the world conversion capacity and 40 percent of enrichment capacity is controlled by Russia. In 2023, Russia supplied 27 percent of U.S. enriched uranium, and also 26 percent of EU enrichment services. The procurement strategies are being transformed by sanctions, countermeasures in the form of export bans, logistical obstacles, including the expensive rerouting of the uranium exports of Kazakhstan by the Russian ports. China, South Korea and the UAE are on a blistering pace of reactor construction, with uranium off-take pacts being established as a strategic asset. Within this context, the country that dominates uranium chains might be able to gain a leadership advantage in AI.

6. Nuclear Renaissance (Pushed by Hyperscaler).

Nuclear restarts are being financed faster by tech giants than ever. The example of Microsoft buying Three Mile Island and the 1.1 GW contract of Meta in Illinois is a demonstration of the hyperscalers readiness to pay hundreds of millions of upfront to get baseload in the long term. The U.S. has 94 active reactors and 18 retired or retiring with almost half of them being reviewed so as to be restarted. However, their transfer to the Internet demands significant improvements – renewing of the licenses, cybersecurity integrity against the 70 percent increase in utility cyberattacks, and reestablishing the manufacturability of uranium fuel rods.

7. Reprocessing and Advanced Reactor Alternatives.

The use of reprocessed uranium (RepU) in Cruas-Meysse reactors in France provides a partial supply-chain bypass: RepU does not require the conversion step and can be re-enriched to be re-used, possibly saving 25 percent of the natural resources and also producing 30 percent less CO 2 emissions compared to natural uranium. Fissiles Fast breeder reactors (FBRs) which have the ability to produce greater fissile fuel than they burn by enriching the plentiful U-238 into plutonium, have the potential to dramatically cut down on the enrichment requirements. The BN series of Russia and the prototype FBR at Kalpakkam of India have proven to be operationally viable, but the Western programs are skeptical following cost and material setbacks in the past.

8. Baseload vs. Green Reliability Premium Economics.

A twenty four hour low-carbon power is more expensive than natural gas. The onsite nuclear is estimated to be $77/MWh in the U.S. when large compared to gas with a carbon price of 100 tons, estimated at 91/MWh. However, solar and wind have the disadvantage of intermittency and transmission costs, although they are cheaper at 2526/MWh in favorable conditions. The combination of nuclear, renewable, battery storage and gas peaking plants is enabled by hyperscalers to adjust between cost and reliability against emission. Such and strategy is based on the fact that the move which is aggressive on nuclear expansion cannot displace other generation technologies in the near future.

The alliance of the inexorable power demand of AI with the lethargic realities of nuclear is producing a structural crisis in world energy markets. The shortage in supply of uranium, bottlenecks in the middle, and reliance on geopolitics are now colliding with the hyperscaler-induced urgency, transforming both the economics and geopolitics of baseload generation. The coming decade will not be marked by the company that builds the fastest data centers, but rather by whoever controls the atoms that make them run, to those in the energy market who are also technology investors and policy strategists.