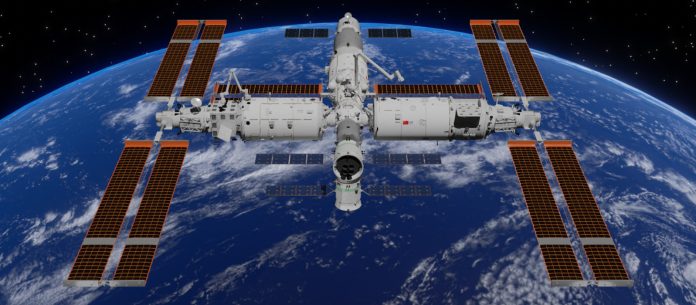

Not every day does a spacecraft window crack, caused by a particle smaller than a millimeter, unleash a nationwide space rescue operation. But in late 2025, China’s Shenzhou-20 mission faced just that: a shard of orbital debris, traveling at hypervelocity, compromised the viewport of the return capsule, which forced the country’s first-ever emergency launch in manned spaceflight history. Short reaction times showed not just the engineering resilience but also the maturity of China’s space infrastructure, setting the scene for more ambitious undertakings toward the Moon and beyond.

1. Shenzhou-20 Emergency: Engineering Under Pressure

This unfolded as an emergency in early November when routine pre-departure checks revealed penetrating cracks in the capsule’s outer pane. Although less than 1 mm wide, this presented unacceptable risks at reentry when thermal and mechanical stresses could lead to catastrophic failure. The engineers diagnosed the threat, coordinated the crew transfer to Shenzhou-21, and launched the uncrewed Shenzhou-22 as a replacement lifeboat-all within 20 days. Thousands of personnel were mobilized for the operation, which required precise scheduling of the Long March 2F rockets, underlining China’s capability for rapid orbital crisis management.

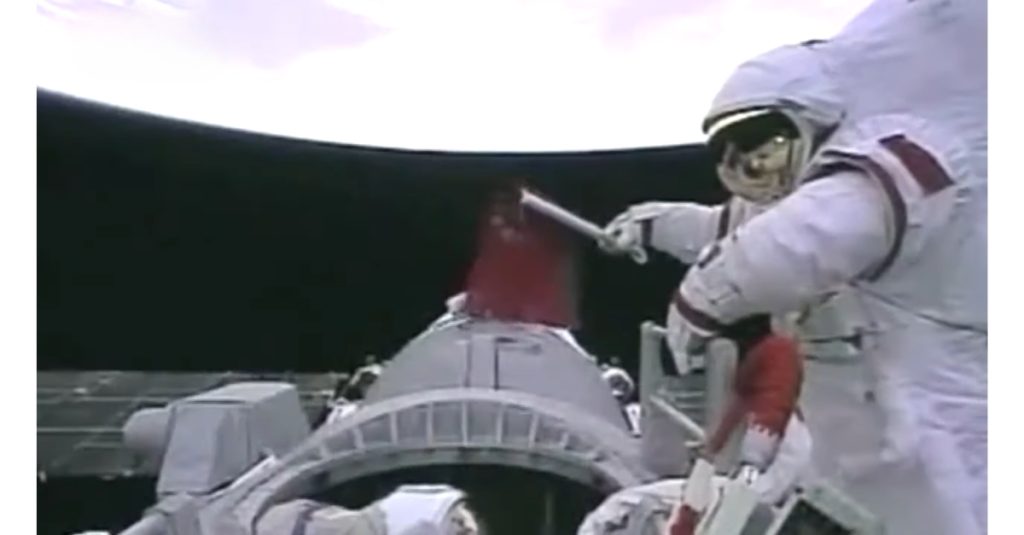

2. Spacewalks and Robotic Arm Precision

In new and improved Feitian EVA suits, the Shenzhou-21 crew performed an eight-hour extravehicular activity to photograph and analyze the damaged viewport. Supported by Tiangong’s robotic arm, astronauts installed debris shielding and changed out thermal control covers. Work in this nature is representative of the merging robotic systems into human spaceflight operations whereby astronauts can execute complex repairs with minimal exposure to hazard.

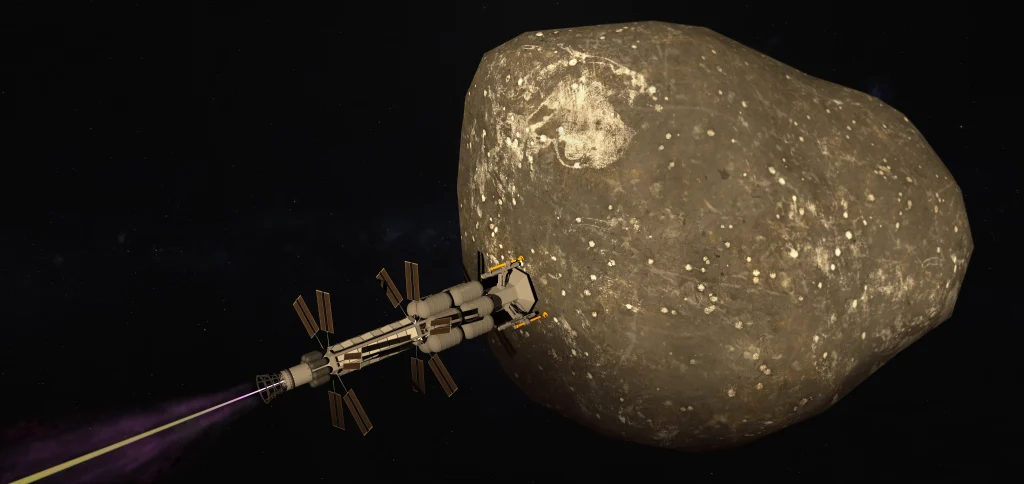

3. Tianwen-2: Dual-Target Deep Space Mission

Launched on May 29 aboard a Long March 3B, Tianwen-2 will sample asteroid 469219 Kamoʻoalewa and, afterward, observe the comet 311P/PanSTARRS. This probe is expected to return asteroid material by November 2027, then head on a multi-year trip to the comet. A landing on Kamoʻoalewa was even more difficult compared to a lunar landing because the gravity is much weaker, needing precision anchoring and sampling mechanisms. It had 11 instruments for geological, compositional, and dynamic studies that would feed into general asteroid defense and resource utilization efforts at China.

4. Asteroid Defense: Kinetic Impact Verification

The newly unveiled asteroid defense plan from China includes a kinetic impact demonstration, firing off an observer to characterize the target asteroid, and then a high-speed impactor that would change trajectory. It requires precision; striking a body only hundreds of meters across from tens of millions of kilometers away needs autonomous navigation with errors of just dozens of meters. Space-based monitoring will be supplemented with assets such as the “China Compound Eye” radar network on the ground as part of the multi-orbit detection and mitigation system.

5. Long March-10: Heavy-Lift for Lunar Ambitions

The Long March-10 rocket, for manned lunar missions, conducted static fire tests of its seven YF-100K engines, collectively producing nearly 1,000 tons of thrust-a record for the country. Its triple-core first stage allows for modularity, and the 10A variant will serve low Earth orbit missions. Recovery ships like Linghangzhe are using net capture instead of landing legs to better their reusability. Vertical assembly buildings are ready at Wenchang spaceport in support of the dual-launch lunar mission profile that will see Mengzhou and Lanyue rendezvous in lunar orbit before descending to the surface.

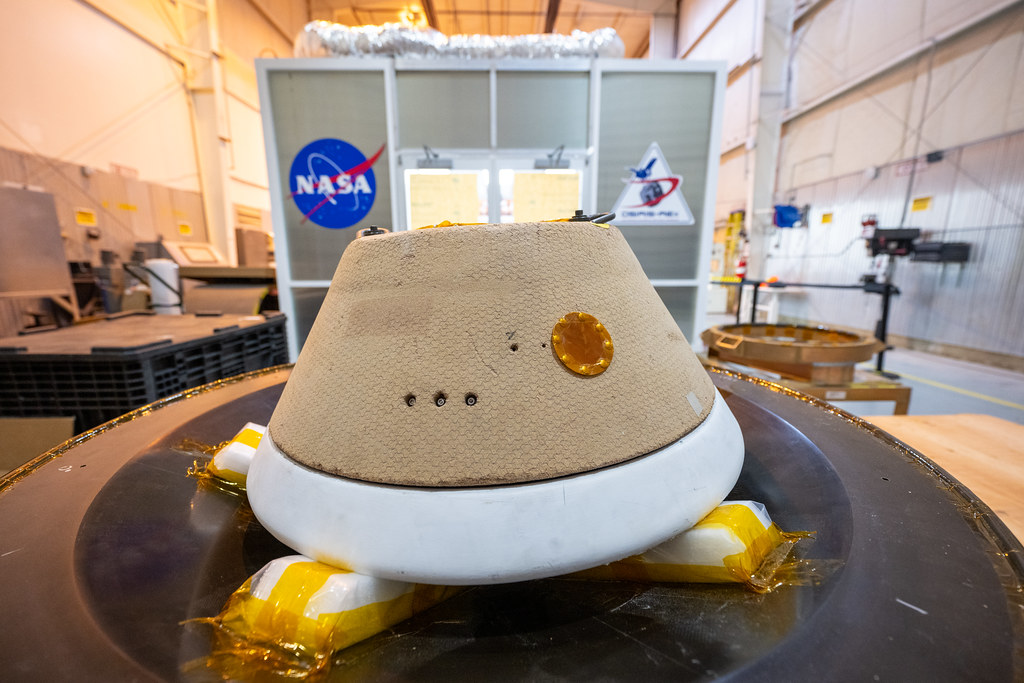

6. Mengzhou Spacecraft: Safety and Modularity

The zero-altitude escape test of Mengzhou had validated its integrated emergency system, where the functions of launch abort and crew survival were integrated into a single architecture. It is able to take seven astronauts into space and is offered in both LEO and deep-space variants; the latter weighs 26,000 kg in lunar missions. Equipped with a modular design, it can dock with separately launched landers, enabling several options for sustained lunar operations.

7. Lanyue Lunar Lander: Precision Touchdown Capability

The propulsion, guidance, and interface compatibility of the Lanyue lander were tested in a simulated lunar takeoff and landing. This “lunar life center” can host long-term missions, rovers, and scientific payloads. Its systems leverage heritage from the Tianwen-1 Mars lander but are adapted for lunar dust, thermal extremes, and varied terrain.

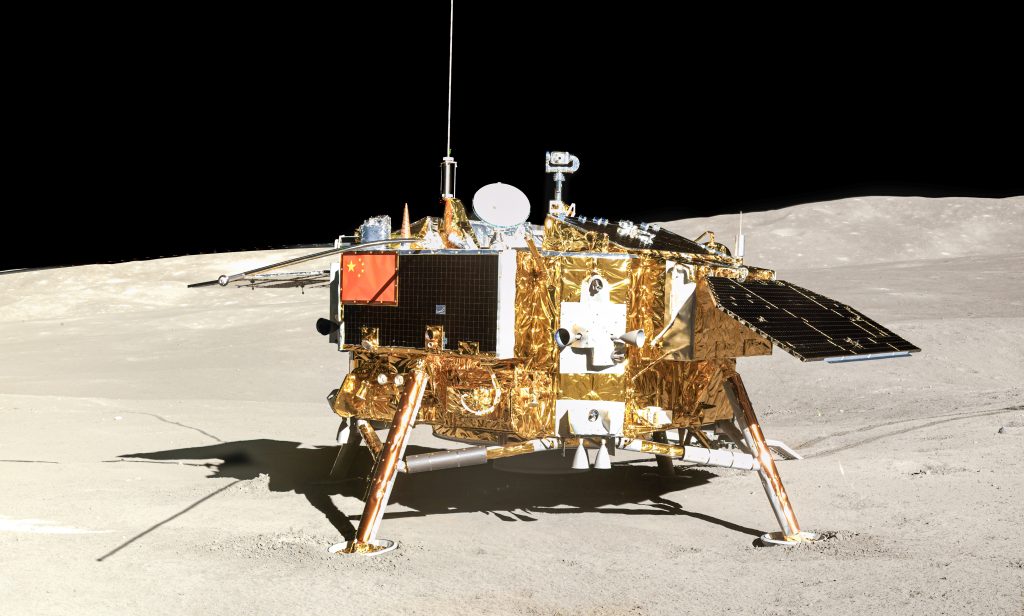

8. Chang’e-7: South Pole Resource Prospecting

The South Pole Slated for a flight in 2026, Chang’e-7 will carry a hopper vehicle designed to jump into permanently shadowed craters in its quest to find water ice. It is to be equipped with vertical solar panels and be capable of autonomous terrain analysis that will enable such missions in dark, rugged terrain. Proof of water ice could provide a means to employ in-situ resource utilization and help cut back reliance on Earth-supplied consumables.

9. International Collaboration and Deep Space Economy

China now calls on global partners for sharing asteroid observation data through the International Deep Space Exploration Association, co-developing payloads, and taking part in lunar missions. Under the vision of deep space economy, China includes mining of metals and volatiles from asteroids, building space-based infrastructures, and interplanetary transport networks. From emergency crew rescue to propulsion breakthroughs, China’s 2025 space milestones signal a maturing capability that commits to human spaceflight safety, robotic precision, and deep space exploration in equal measure. Targeting the Moon for 2030, and entering practical testing for asteroid defense, the trajectory is set firmly toward sustained presence beyond Earth orbit.”