It is also said that “you can’t manage what you can’t measure,” and nowhere more pressing than in the race to prevent global warming from exceeding the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C limit. As COP30 looms, the climate policy community is confronted with a reckoning: just 25 nations, accounting for only 20% of emissions, have put in revised Nationally Determined Contributions, and of these, only the United Kingdom’s plan is Paris-compatible.

The residual carbon budget for 1.5°C once considered a buffer is now a fast-disappearing lifeline, set to be depleted in under three years if present emissions continue.

1. The Carbon Budget: A Narrowing Margin for Error

The idea of a carbon budget, developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, relates cumulative CO₂ emissions to the likelihood of remaining below certain temperature targets. As of early 2025, the remaining global carbon budget to achieve a 50% probability of keeping warming at 1.5°C is around 130 billion tonnes of CO₂. With the annual rate of emissions of around 53 billion tonnes, this budget would be exhausted in a little more than three years, as per the latest Indicators of Global Climate Change report. Concordia University’s Damon Matthews emphasizes the seriousness: “It’s become a question of how low we can keep the temperature peak, and can we put in place measures to return from that temperature peak in the latter half of the century.” The report’s verdict is unequivocal: “Every increment matters” in the battle to prevent ratcheting up climate effects, from permafrost melt to wildfire spread.

2. NDC Submissions: A Glaring Implementation Gap

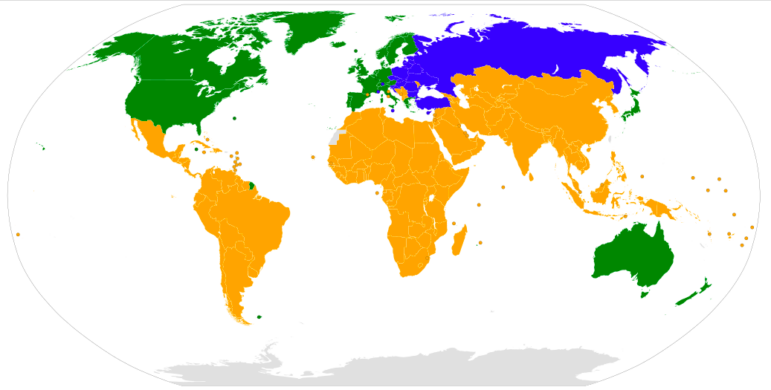

The architecture of the Paris Agreement is based on nations submitting and revising NDCs that together trace a trajectory towards climate security. The gap between intent and action is, however, increasing. Just five of the G20 nations Canada, Brazil, Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom have so far submitted 2035 NDCs, even though the G20 is responsible for approximately 80% of total emissions. The Climate Action Tracker currently only classifies the UK’s plan as “1.5°C compatible.” This lack of ambition is most severe in big economies whose commitments and actions will determine the tone for global mitigation.

3. The Science of Carbon Budgeting and Uncertainties

Carbon budget estimates are based on the transient climate response to cumulative emissions, but there are uncertainties galore. The IPCC Sixth Assessment observes that the budget for a two-thirds probability of limiting warming to 1.5°C remains around 420 billion tonnes of CO₂, with a ±400 billion tonne uncertainty based on geophysical and socio-economic factors. Non-CO₂ forcers like methane and nitrous oxide make things more difficult, with methane cuts providing a fast route to short-term cooling. The pace of warming due to human causes is now 0.27°C per decade the highest in recorded history.

4. The Data Deficit: Why Climate Policy Trails Reality

In contrast to the finance world, where up-to-date data supports fast decision-making, climate policy is bogged down by old, patchy, and non-standard data. The five-yearly or annual reporting cadence of the UNFCCC’s Global Stocktake generates perilous delays. It would be impossible to imagine economies without rapid access to credible data, the main article notes. But when climate is in question, “the pace of climate change tends to outrun the available data.” The consequence: governments are flying blind, too slow to respond to the latest signals on the climate.

5. Satellites and the Digital Revolution: Real-Time Climate Monitoring

Advances in technology are starting to fill the data gap. NOAA’s GOES satellites, outfitted with the Advanced Baseline Imager, now can detect large methane leaks in real time as often as every seven seconds. “This technology demonstration gives us confidence in our capability to track methane emissions and respond better to stakeholder requirements,” says NOAA’s Shobha Kondragunta. The experiment’s combination of satellite, airborne, and ground sensors provides unprecedented precision in measuring emissions, aiding both mitigation and accountability. New nanosatellite constellations, e.g., South Korea’s NarSha, are taking the envelope even further, able to measure as small as 100 kilograms per hour emissions with ground sampling distances of less than 25 meters.

6. Digital Climate Accountability: Toward a Financial-Grade Infrastructure

A paradigm shift is underway in climate governance, with calls for a Digital Climate Accountability Framework that mirrors the transparency and immediacy of financial reporting. Such a system would integrate data from satellites, IoT sensors, and standardized national inventories, analyzed by AI for accuracy and equity. Real-time dashboards would be able to show progress country by country, flag laggards, and enable enforcement through the use of tools such as carbon pricing or focused finance. The UNFCCC Global Climate Action Portal is being transformed from a recognition platform to one that tracks and will be able to offer “progress data” to guide and speed up policy action.

7. The Stakes for COP30 and Beyond

The next round of NDCs, due ahead of COP30, represents a critical juncture. The African continent, already suffering its deadliest climate crisis in over a decade, stands to benefit from alignment of climate and development goals potentially lifting 175 million people out of poverty. Yet, only Somalia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have submitted updated plans so far. The globe is waiting for global leadership from the European Union, China, and India, whose NDCs will be crucial in deciding whether the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal remains within reach.

The science is clear: “The window to stay below 1.5°C is closing fast,” declares Prof. Joeri Rogelj. “What happens this decade will decide how soon and how rapidly 1.5°C of warming is achieved. They need to be urgently cut back in order to deliver the Paris Agreement climate objectives.” No longer is the issue whether technology is available, but whether governments have the speed required by the numbers and by the planet.