It’s not every decade that an object from another star system streaks through the solar system-and never before has such a visitor been clocked at 130,000 miles per hour. Comet 3I/ATLAS, only the third confirmed interstellar object, is now outbound after skimming past the Sun on October 29, 2025, and reaches its closest approach to Earth on December 19th at 1.8 AU. Though far beyond naked-eye visibility, it’s an unprecedented opportunity for astronomers to study a high-velocity comet from another stellar nursery.

1. The Fastest Solar System Visitor Ever Recorded

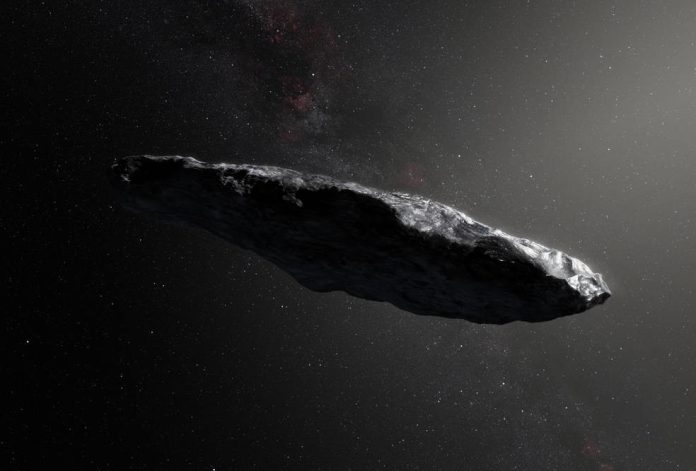

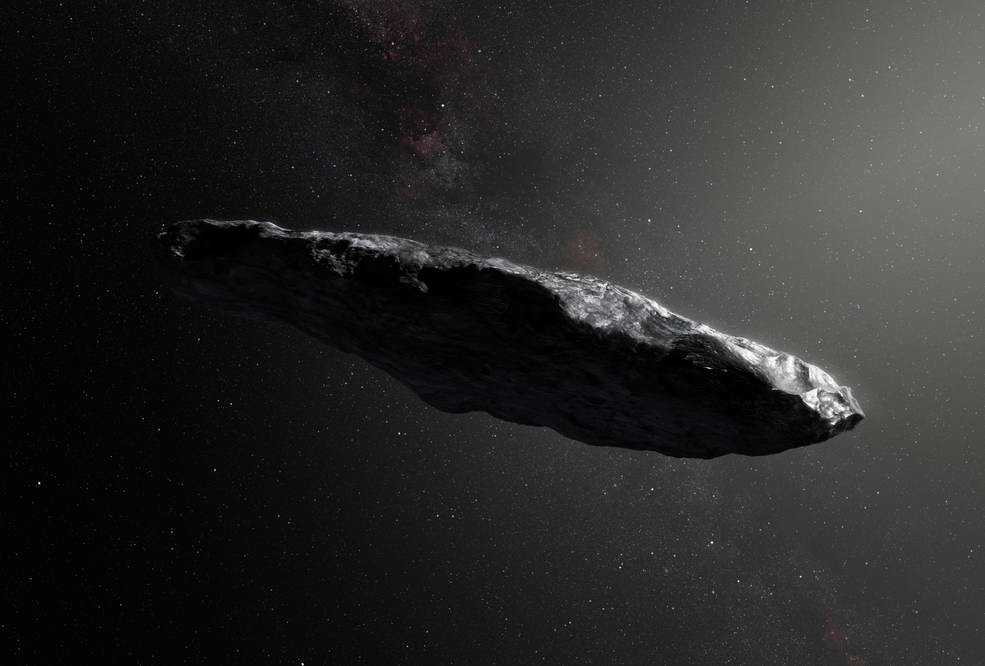

3I/ATLAS’s heliocentric velocity of 58 km/s is much higher than either 1I/’Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov. Its velocity is a relic of billions of years drifting through interstellar space and being gravitationally slung around both stars and nebulae. The path is hyperbolic in shape, meaning it will never return. As David Jewitt, a researcher at UCLA, explained, “No one knows where the comet came from. It’s like seeing a rifle bullet for a millisecond.”

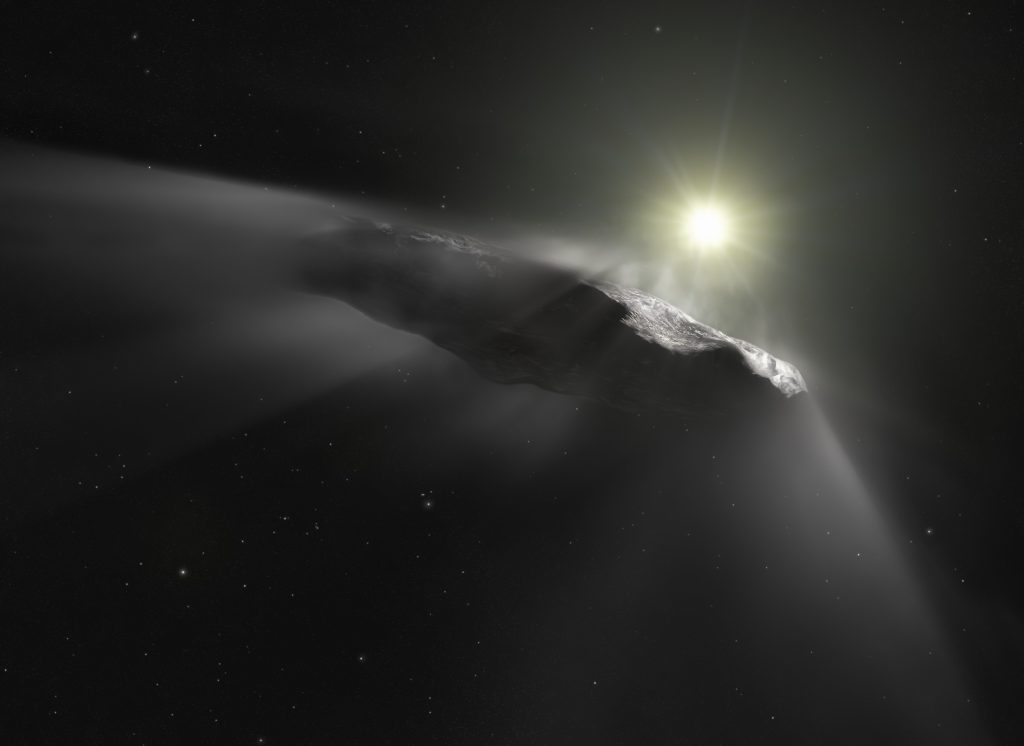

2. Outgassing, Not Alien Engines

Early speculation about exotic propulsion gave way as scientists measured its non-gravitational acceleration and found it consistent with cometary outgassing. Thermophysical models show that sublimation of CO and CO₂ from sub-percent active surface areas reproduces both the magnitude and direction of the acceleration. In striking contrast to 1I/‘Oumuamua, whose anomalous acceleration was devoid of any detectable outgassing, the acceleration measured between 3×10⁻¹⁴ and 2×10⁻¹⁰ AU/day² is many orders of magnitude smaller than ‘Oumuamua’s, firmly placing 3I/ATLAS into the natural comet category.

3. Imaging Challenges and Mars Flyby

In early October, 3I/ATLAS passed just 18 million miles from Mars, its closest planetary encounter. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter rotated its HiRISE camera normally used for Martian terrain—to capture the comet at 19 miles per pixel. MAVEN’s ultraviolet spectrograph mapped hydrogen and hydroxyl in the coma, setting upper limits on deuterium-tohydrogen ratios that may hint at its birthplace. Even Perseverance’s Mastcam-Z recorded a faint smudge, though long exposures produced star trails.

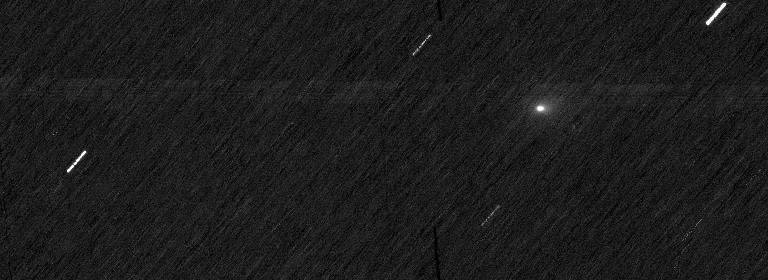

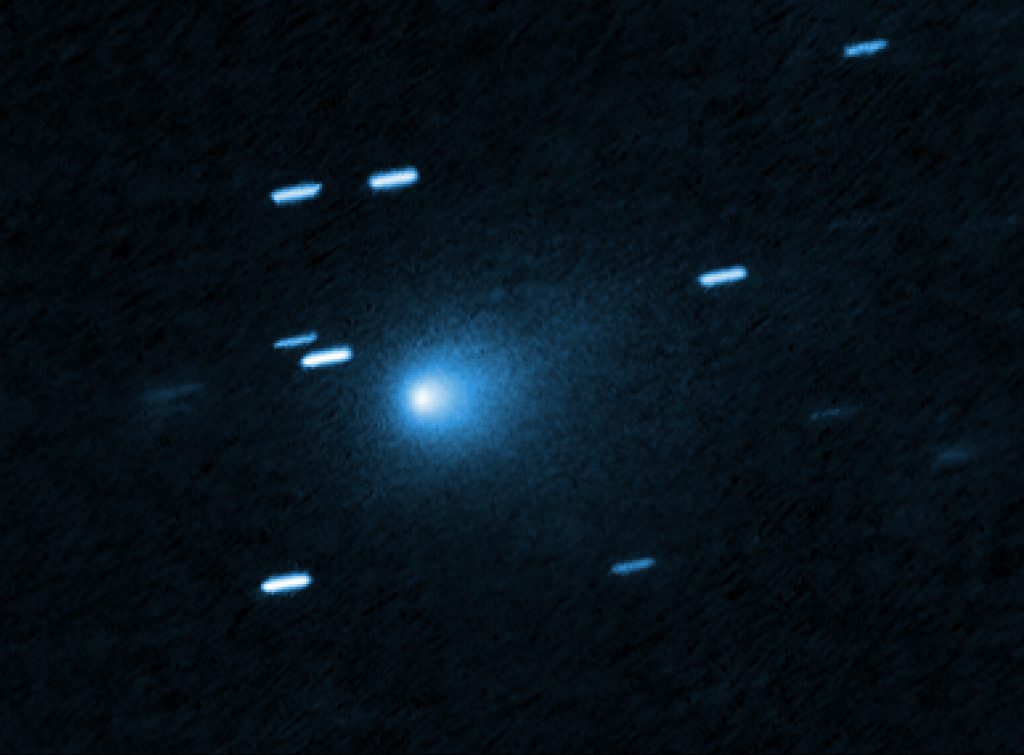

4. Size and Structure from Hubble

Hubble’s sharpest-ever images of 3I/ATLAS constrain its nucleus to be between 320 meters and 5.6 kilometers in diameter. Still, the solid core remains unresolved due to being cloaked in a dust plume coming off the Sun-facing side and a faint tail. The estimated dust-loss rate strengthens this classification as a comet because it is consistent with comets first detected around 300 million miles from the Sun.

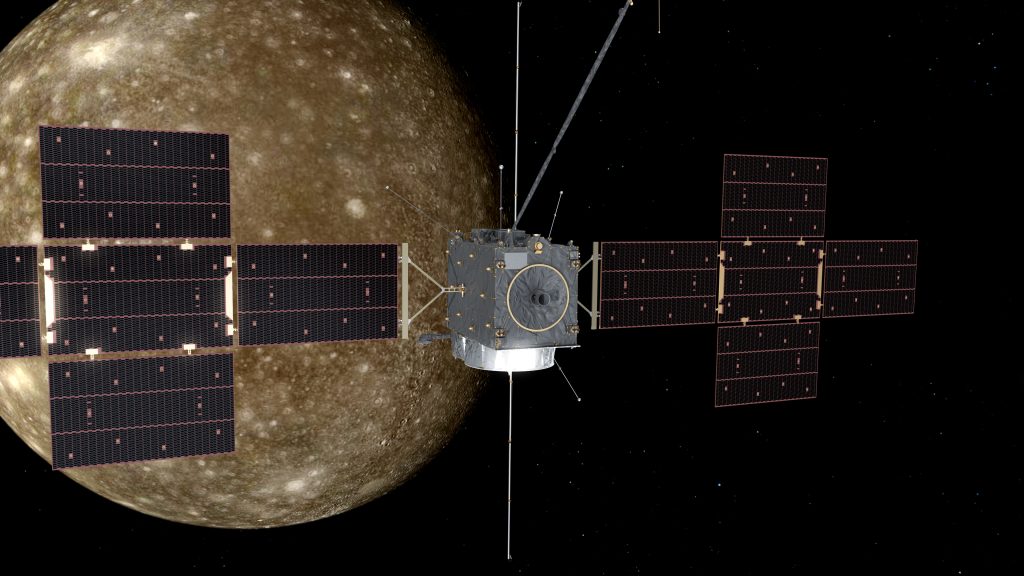

5. The Unique View of JUICE

ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, JUICE, observed the comet between November 2–25, shortly after perihelion, when activity was most vigorous. Even a partial navigation camera frame shows a bright coma with two distinct tails: one of ionized gas arcing upwards due to the solar wind, the other of dust particles trailing off to the lower left. Full high-resolution data from JUICE’s science instruments won’t arrive till February 2026; that might prove the key to detecting unusual chemistry in the dust and gas.

6. Thin Disk Likely to Be the Origin

By using astrometry from Gaia DR3, astronomers traced the orbit of 3I/ATLAS back 10 million years and discovered 25 close stellar approaches. None of these had the low relative velocity required for ejection to be plausible, while gravitational scattering over gigayears was also found too weak to have given it its present velocity. A statistical treatment of its three-dimensional velocity against local densities of stars sets its probability of thin-disk origin at 96.6%, indicating star formation in a fairly young, metal-rich region of the Milky Way.

7. Comet Interceptor: The Future of ISO Exploration

The Comet Interceptor of the European Space Agency, scheduled to launch in 2029, will position in space and wait for a still-to-be-discovered comet to come along for a close encounter. Its architecture is one that could be adapted for interstellar objects like 3I/ATLAS: pre-positioning a spacecraft to allow for a speedy interception. Payloads would include high-resolution imagers, spectrometers, and a neutral mass spectrometer to analyze unfamiliar compositions. Such missions could compare planetary system building blocks across the galaxy, potentially detecting organics or amino acids on alien comets.

8. Observing 3I/ATLAS from Earth

For amateur astronomers, 3I/ATLAS will remain a telescopic target only. An 8-inch (20 cm) or larger telescope is needed, with the best viewing in the eastern predawn sky during late November. NASA’s “Eyes on the Solar System” tool offers real-time tracking, and astrophotographers have already captured its multiple jets post-perihelion. While faint, the knowledge gained from each observation contributes to understanding how planetary systems eject icy bodies into interstellar space.

From its staggering speed to its likely birthplace in a thin disk, 3I/ATLAS is a rare probe of galactic planetesimal populations. Coordinated campaigns across Hubble, JUICE, Mars orbiters, and ground-based telescopes turn this fleeing visitor into a detailed case study of how other solar systems form-and how their debris occasionally finds its way to ours.