‘The cost of doing business with Venezuela just got a lot higher,’ warned Claire Jungman of Vortexa, following the US forces’ December boarding of the tanker ‘Skipper’ in December 2025. In one swoop, one seizure revealed the enormous, hidden V1 tanker network, smuggling oil under sanctions across the world, stretching back through its links with Venezuela, Iran, Russia, but also, it seems, beyond.”These “ghost ships” operate outside the purview of conventional surveillance, relying on the ‘regulatory loopholes’ and the ‘sensitivity’ of regional states.

The operational ‘modalities’ of such ‘ghost ships’ have already repatriated millions across the world, where their ‘suspicious’ behavior makes them ‘illegal’ according to Western sanctions. But, with Donald Trump’s promise of ‘tougher seizure policies,’ the entire global situation is soon set to change. ‘Ghost ships’ are actually taken over by pirates, who then sell their cargo, making it ‘compromised.’ They have routes stretching back through Venezuela, then through ‘politically accurate’ routes involving ‘sensitive’ states such as ‘totally cooperative’ Russia. Everything is about ‘regulatory compliance’ here.

1. The Skipper’s High Risk Voyage

The Skipper, an Iranian tanker ship measuring 332 meters, carrying 2 million barrels of oil, half of it bound for Cuba, was boarded by U.S. commandos who “digital spoofed its location off the coast of Guyana as it took on oil from Venezuela. The ship had once changed ownership and been renamed as a result of its “erratic and volatile” history, operating a fictional flag of a stateless ship according to international maritime law when the U.S. exploited it.” Regardless of it originally having been sanctioned in 2022 as “Adisa” as part of an Iranian smuggling ring financing Hezbollah and IRGC-QF.”

2. Shell Companies and False Flags

For instance, the one controlled by Ukrainian national Viktor Artemov is organized around dozens of shell companies incorporated in different countries running from the Marshall Islands to Mauritius. Even though the ownership is masked by shell companies, the name as well as the flag of the ships is constantly changing. It was stated, in line with the notification of the IMO, that Skipper’s Guyana flag status had been canceled. This is something that has been commended as precedent by United Against Nuclear Iran.

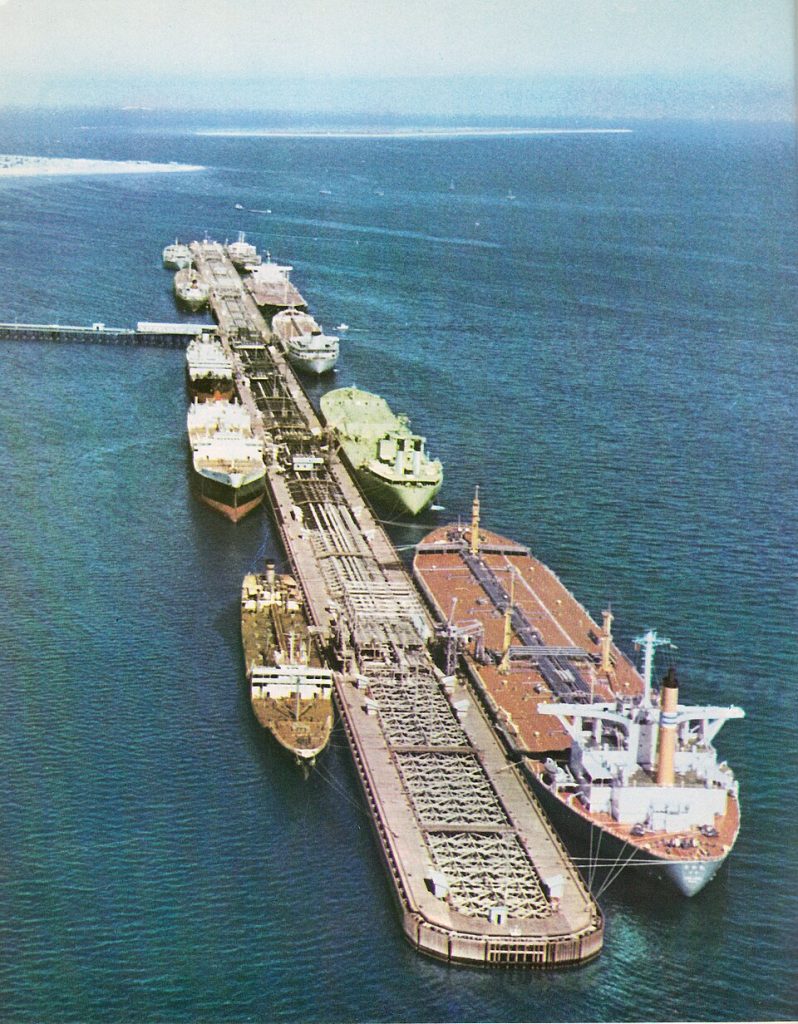

3. International Extent of Dark Ship Transfers

“Dark STS activity numbered 792 in Q3 2025, the highest number since reporting began in 2022,” reported S&P Global Maritime Intelligence. “Of these, 432 involved Russia’s territorial seas, 81 Iran, and 27 in Venezuela. Overall, some 115.2 million barrels of product changed hands through dark STS operations in Q3 2025.” Increased oil prices have continued to trigger this activity, with “sanctioned barrels command[ing] high premiums for those willing to take the risk of confiscation.”

4. Malaysia’s Offshore Hub

East peninsular Malaysia is identified as the world’s largest hotspot for dark fleets. Old and uninsured vessels discharge their commodities offshore. Satellite information from Bloomberg provides an estimate that at least 350 barrels of oil have been traded in the first nine months of the year 2024, worth more than $20 billion. This is for large consignments from Iranian nationals exporting their commodities to China via vessels that are entirely owned by the concerned nationals. Malaysia’s enforcement ability is very weak with regard to its EEZ and is not ready to enforce U.S. sanctions.

5. China’s Plausible Den

Iran’s imports stand at zero, or at least this has been the case since the middle of 2022, although it’s reported to purchase 90 percent of Iran’s exports. Its imports come primarily through “Malaysian” oil; it’s also pertinent to note the Chinese import of oil from Malaysia for the year 2023 has surpassed Malaysia’s domestic production. As reported by Energy Intelligence through the statement of a researcher at Columbia University: “These channels offer Iran’s main customers ‘plausible deniability’ out of secondary sanctions, which allows small refineries to purchase Iranian oil at a cheaper rate as a ‘feedstock’.”

6. Risks of an Aging Fleet

Most of these ‘ghost ships’ are over 20 years old; this is beyond the average lifespan when one considers scrapping, and there is no recognized insurance cover for this tanker. There have been cases like the explosion involving the Pablo tanker in 2024, and this led to the death of three crew members. It has been highlighted by seafarers and experts in the shipping industry as an indicator that chances of collision and possible spillage endanger other passing ships. The massive tanker is capable of carrying 300,000 tons of oil. Clean-up costs for any spilt oil if it were to penetrate the Southeast Asian waters would amount to well over $16,000 for every ton.

7. Legal Issues Arising from Seized Cargo

There is an appeal involved in the case of the tanker ship, the Eventin, carrying Russian oil, and being held by Germany. The ship drifted into the German port due to the failure of the engine and seemed to breach embargoes afterwards. The application of exemptions in respect to the distressed vessel has paused the notifications of seizing the vessel. This is an indication of how complex an issue can become while trying to enforce an embargo on foreign ships that seek refuge or are difficult to trace in terms of ownership by offshore companies.

8. Evasion Technology Shifts

“Ghost” vessels deliberately turn off or fake their AIS tracking or engage in the action of spoofing. It was believed to be located in the Iraqi Basrah terminal in July of 2025, based on its “Skipper” AIS information. However, satellite imagery showed that this tanker was carrying its load in Iran, in Kharg Island. “Transfers of the product from ship to ship in the areas around Venezuela and Malaysia” further mask its origins. These actions were deemed “extremely rare” for usual commercial ships by former Belgian navy man and skipper Frederik Van Lokeren.

9. Geopolitical Reluctance to Enforce

Nations with shorelines, like Malaysian and Indonesian governments, for instance, rarely enforce sanction responses that they are not a part of, opting to instead address their own shoreline issues rather than become embroiled in international political squabbles with other governments. The fact that there is a lack of funds to secure the oceans is merely a conduit to a bigger problem. As Greg Poling with CSIS indicated, it may almost amount to futility for the U.S. to merely place finger-judgments on other nations about how to address the situation, to instead allow the “dark fleet” to exploit the loophole on the export of oil from sanctioned nations for

The Skipper hijacking sparked insight into this complex world of the ghost fleet, a world of ships which combines politics, economics, and the risks of the ocean. The Trump willingness to get his hands dirty in this world could be the turning point from the money-punishing world to the world of getting his hands dirty in it. It could be the birth of the world of a new age of a world which is protected, or it could be the next chapter of the world sailing under different names.”