The accelerating accumulation of orbital debris has become less a remote concern and more an immediate engineering problem. More than 130 million pieces of debris in LEO alone now orbit at over 7.8 kilometers per second, each one with the potential to cause catastrophic damage. The recent University of Surrey study in *Chem Circularity* reframes this hazard through a lens more familiar to environmental science than aerospace-treating space debris and aerospace waste within the framework of a circular economy.

1. Linear to Circular in Space Systems

Historically, space missions have been almost completely single-use. Rockets jettison stages into space, satellites drift into graveyard orbit, and precious material, such as titanium alloys, rare earth elements, and high-grade composites, are lost forever. It is to this scenario that the Surrey team now plans to embed principles of reduce, reuse, and recycle into mission design, enable lengthier lifetimes for spacecraft with in-orbit servicing, and recover materials for reusage. “A truly sustainable space future starts with technologies, materials and systems working together,” said Jin Xuan, a senior author.

2. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins – the Enablers

The study highlights the role that AI-driven modeling and digital twins can already play in minimizing waste and optimizing resource use. Virtual twins of spacecraft-constantly updated digital avatars-can simulate the structural and thermal behavior over the life cycle of a mission with minimal expensive and material-intensive physical testing. AI algorithms develop predictive maintenance, collision avoidance, and mission design optimization, building upon approaches shown to work well in Earth observation digital twin frameworks.

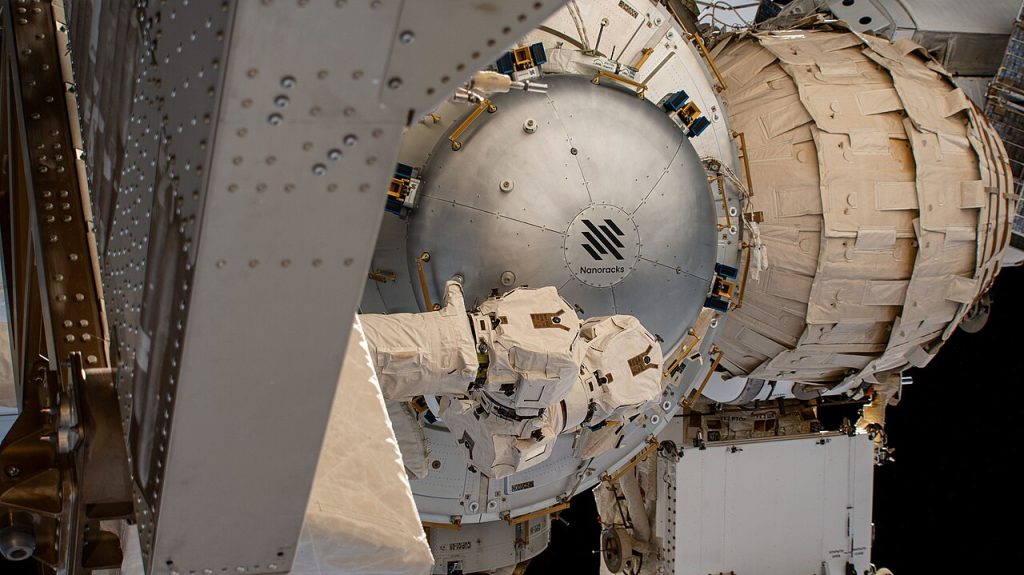

3. Technologies for Mitigation and Removal

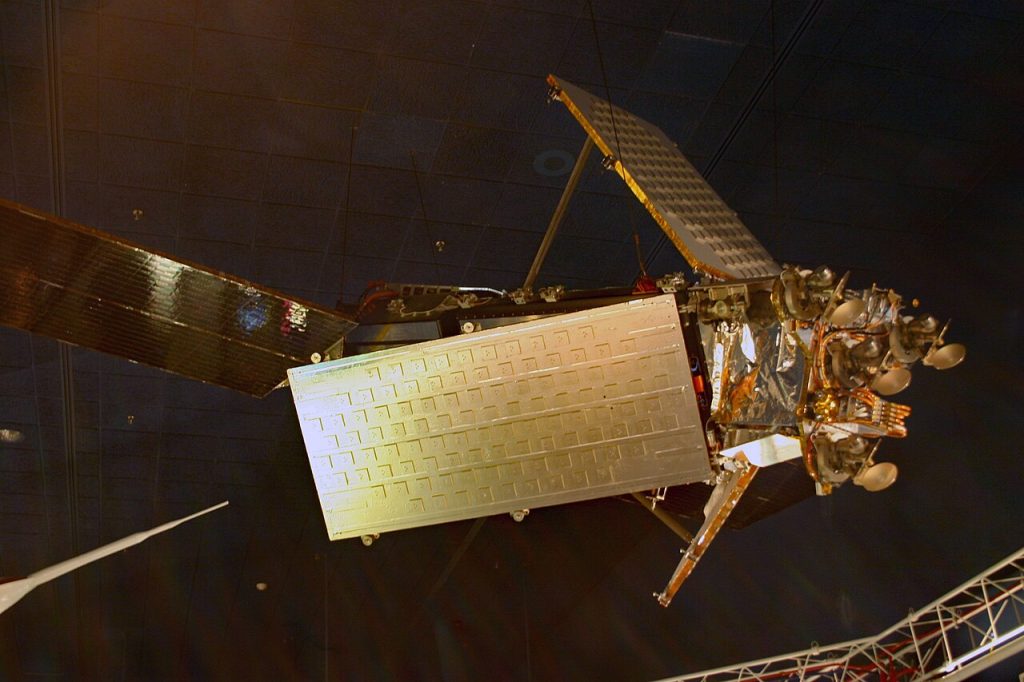

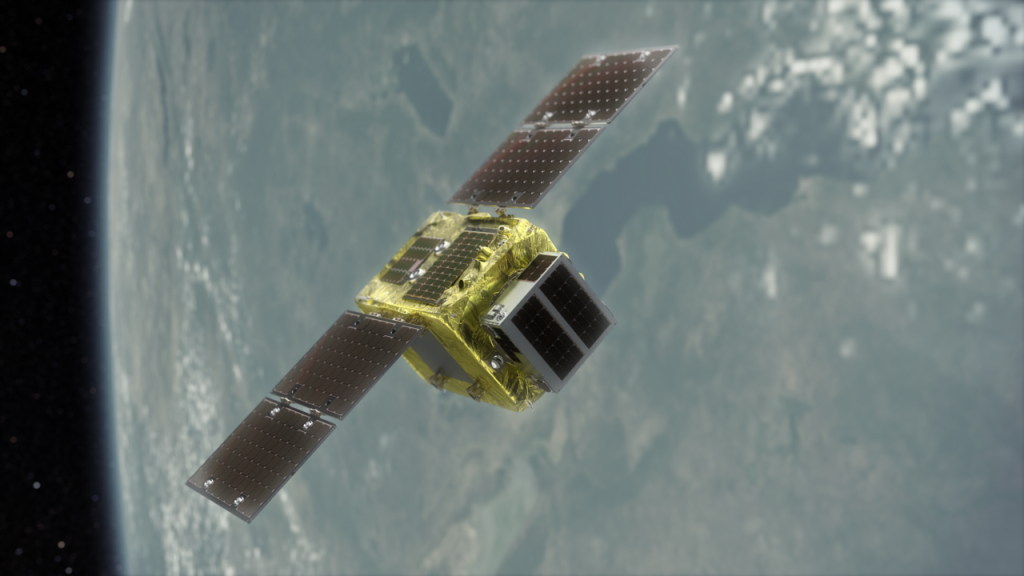

Active debris removal is developing from experimental into operational readiness. Capture systems, which span from nets and robotic arms to magnetic docking, will be used in ESA’s ClearSpace-1, Astroscale’s ELSA-d, and NASA’s ADRV. Contactless approaches, like laser ablation, are being refined to nudge smaller debris onto decaying orbits. This prepares for alignment with circular-economy thinking by enabling potential material recovery to feed into in-space manufacturing processes, rather than mere disposal.

4. Material Recovery and In-Space Recycling

Funding by the European Innovation Council’s space debris sustainability portfolio will go towards projects that treat the debris as a resource in and of itself. Other examples include DEXTER, which would convert recovered aluminum into propellant, and gEICko, developing gecko-inspired adhesives for capturing non-invasively. Such initiatives envision orbital recycling plants capable of processing metals, composites, and electronics from defunct satellites into raw feedstock for additive manufacturing.

5. Collision Avoidance and Traffic Management

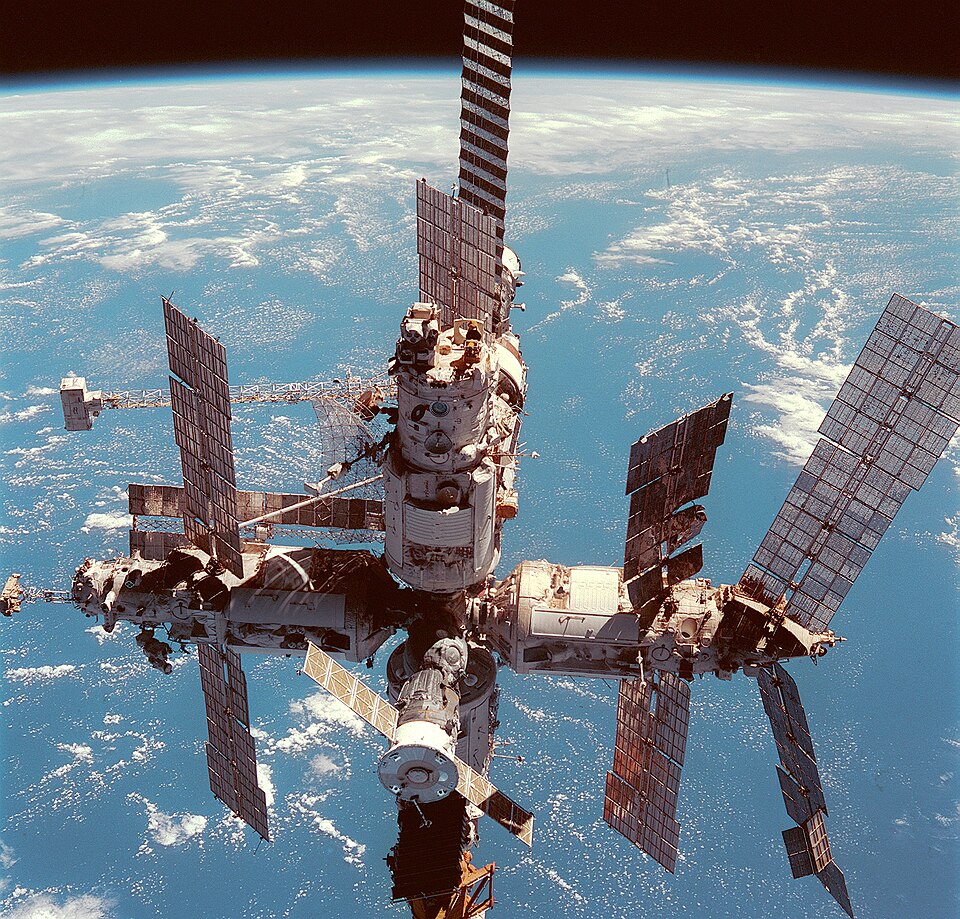

More than half of all LEO collision risks are contributed by debris, and the ISS itself has carried out 14 avoidance maneuvers in just five years. Enhanced space traffic management systems, like those under development by private operators, bringing together radar, optical, and in-situ sensor data, lower the tracking range of objects down to the sub-10 cm range. On these scales, a 1-centimeter fragment can carry enough kinetic energy to penetrate pressurized modules.

6. Design for Failure and Modular Architecture

Circularity starts with design. Modular spacecraft architectures enable in-orbit replacement and upgrades of components. This strategy extends service life and reduces the frequency of launches. “Design for demise” strategies are being employed to ensure that, when components reenter, they fully disintegrate and do not reach the surface as hazardous debris. Biodegradable materials, including satellite panels made from wood, are under consideration.

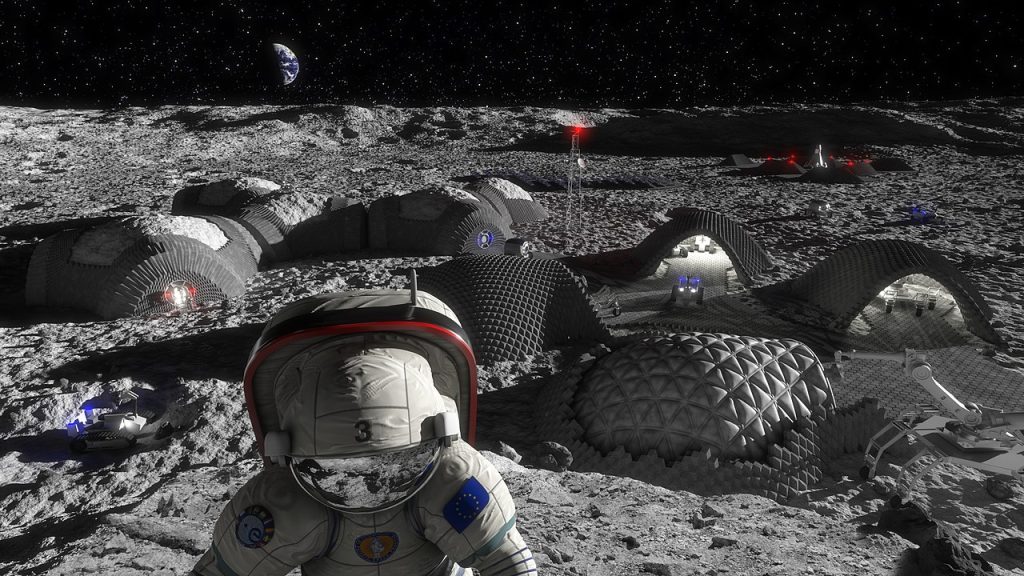

7. Incorporating In-Situ Resource Utilization

Future closed-loop systems will combine debris recycling with ISRU and fuse the regolith-derived materials from the Moon or the asteroids with recovered orbital metals, enabling in-space manufacturing of structural components with reduced dependency on Earth-launched materials and decreased rocket launch emissions.

8. Policy and Regulatory Frameworks

Technological innovation needs to be supported by enforceable governance: existing guidelines, from ESA’s “Zero Debris” approach to the UN’s long-term sustainability principles, are all voluntary. One can already hear proposals for reducing post-mission disposal timelines from 25 to less than five years, end-of-life deorbiting, and incentivizing debris removal through procurement contracts or “debris-as-a-service” models.

9. Cross-Sector Lessons and Earth Applications

The circular strategies envisioned for space echo themes in much more earthly industries: automobile remanufacturing and electronics recycling. Lessons to be learned from these sectors-modularity, material recovery, lifecycle tracking-inform aerospace sustainability, while innovations regarding space-grade recyclable composites and AI-based maintenance could feed back into Earth-based manufacturing efficiency.

As private launches proliferate and commercial stations get ready to backstop the ISS, the orbital environment is experiencing unparalleled pressure. But without systemic adoption of circular-economy principles underpinned by AI, advanced materials science, and robust regulation, the very infrastructure designed to expand humanity’s presence in space may serve instead to accelerate its enclosure.