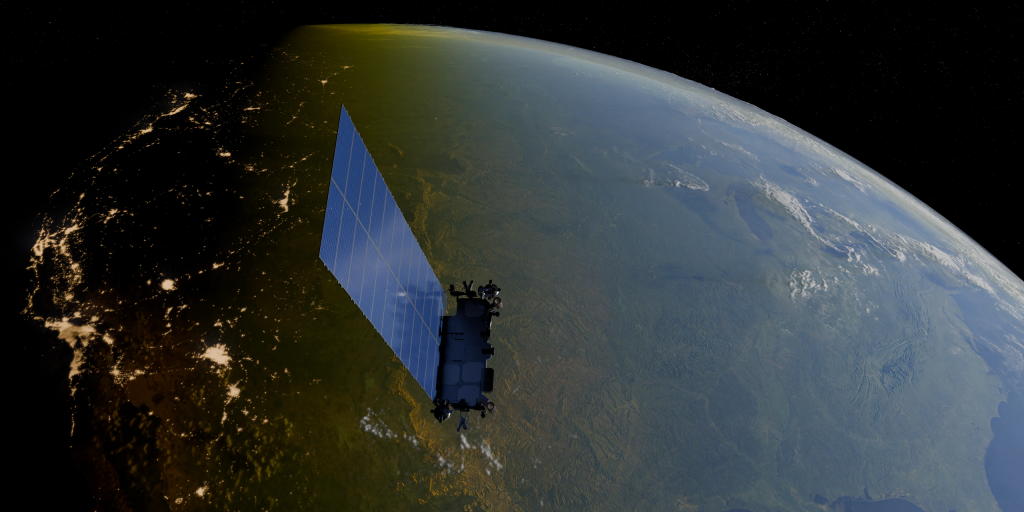

That the next great leap in AI infrastructure could happen hundreds of kilometers above Earth is no longer a matter of speculation-it’s a declared ambition. Google’s Project Suncatcher, SpaceX’s Starlink evolution, and Amazon’s yet-to-be-detailed orbital compute strategy are coalescing into a competitive push to build data centers in Low Earth Orbit-LEO. These aren’t just satellites; they’re high‑performance AI compute nodes designed to operate in the harshest environment humans have ever placed silicon.

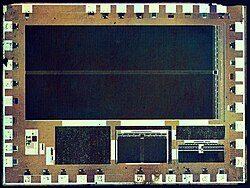

1. Radiation-Hardened AI Accelerators

Google’s Trillium‑generation TPUs have already been tested under particle accelerator conditions to simulate levels of LEO radiation. As Sundar Pichai says, “Early research shows our Trillium-generation TPUs… survived without damage when tested in a particle accelerator to simulate low-Earth orbit levels of radiation.” The requirements for space-based AI are imposing because cosmic rays and charged particles will cause bit flips and performance degradation in the transistors.

Radiation hardening techniques span physical shielding-using high‑Z materials-all the way to architectural techniques such as ECC memory and triple modular redundancy on logic paths. Those techniques have been well understood and used within aerospace avionics; now they need to be adapted for high‑density AI accelerators without crippling their performance‑per‑watt.

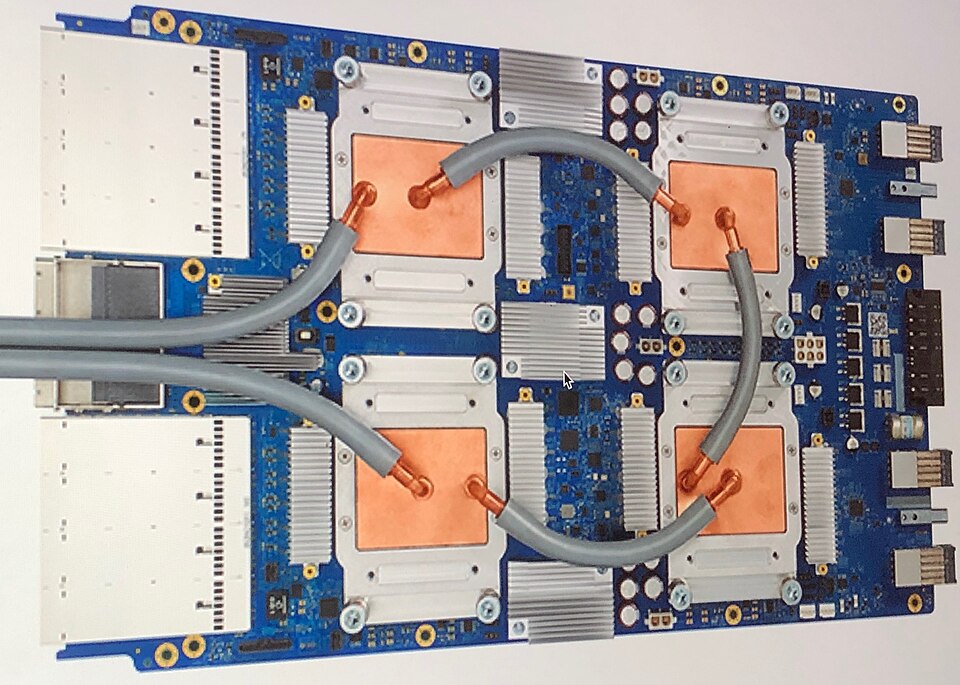

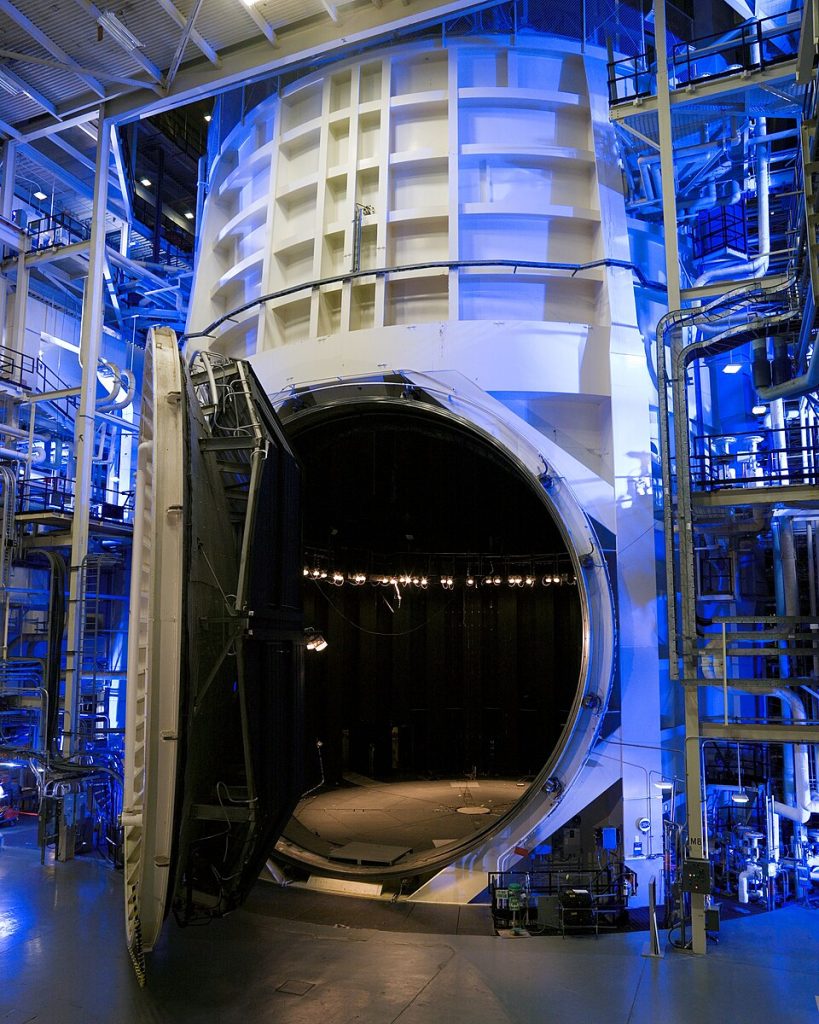

2. Vacuum Thermal Management

Cooling high-power electronics in space is fundamentally different from terrestrial data centers. Without convection, waste heat must be rejected via radiation, which is highly dependent on the Stefan-Boltzmann law. Google’s current plan of heat pipes and radiators follows established spacecraft thermal control, but scaling this to multi-kilowatt AI workloads is no trivial task. In vacuum, radiator area scales inversely with the fourth power of operating temperature, making low-temperature rejection particularly mass-intensive. Advanced concepts, like liquid droplet radiators, could cut radiator mass by more than 90% relative to solid panels by spraying micrometer-scale droplets across a controlled trajectory to radiate heat before recapture. Such systems are inherently micrometeoroid-resistant and could be deployed in compact form factors-each highly critical to launch mass constraints.

3. Optical Intersatellite Links for Distributed Compute

To equal terrestrial data center interconnect speeds, orbital AI nodes must exchange data at terabit‑per‑second rates. Google’s research cites dense wavelength‑division multiplexing and spatial multiplexing as viable paths, with close‑formation flying hundreds of meters apart closing the link budget. Bench‑scale demonstrators have already achieved 1.6 Tbps bidirectional throughput between transceivers. A parallel proof point comes from SpaceX’s Starlink constellation: each satellite carries three optical intersatellite links capable of up to 200 Gbps, while recent tests of a “mini laser” achieved 25 Gbps over 4,000 km to third‑party spacecraft. Integrating such free‑space optical systems into AI compute constellations would enable distributed model training and inference without constant ground relay.

4. Orbital Dynamics and Formation Control

Maintaining kilometer‑scale clusters in sun‑synchronous orbit requires precise station‑keeping. Google’s team uses Hill‑Clohessy‑Wiltshire equations, augmented with differentiable physics models that account for Earth’s gravitational harmonics and atmospheric drag at ~650 km altitude. Their simulations indicate that modest propulsion corrections can maintain stable 81‑satellite clusters, whose nearest‑neighbor distances oscillate between 100–200 m. This close formation is necessary to enable high‑bandwidth optical links but makes collision avoidance more complex, particularly as congestion increases in LEO.

5. Launch Cost Economics

Even with technical feasibility, economics will ultimately determine deployment pace. Google estimates that with continued learning rates in reusable rocketry, launch prices could decrease below US$200/kg by the mid‑2030s. With its 100,000 kg LEO capacity, SpaceX’s Starship could theoretically drive costs down toward the US$100/kg mark, though market control may put a damper on price decreases. Historical data from the reusable launch vehicle fleet indicates that economies of scale for large payloads are reached at very high annual launch frequencies-20+ flights per year for 20‑ton class payloads correspond to a per‑kg cost of less than US$1,000. For orbital AI data centers, these economics will determine whether scaling beyond prototypes is economically feasible.

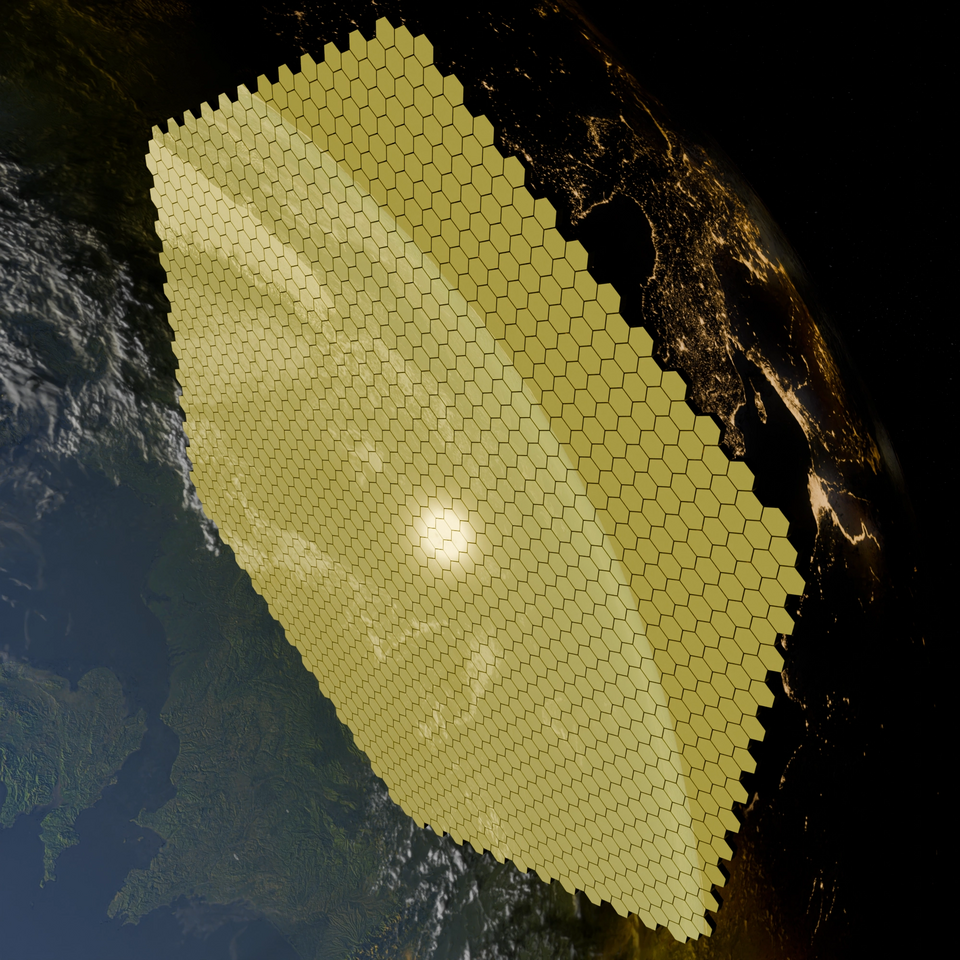

6. In-Orbit Power Generation and Energy Storage

One core advantage of orbital compute is continuous solar power. In sun‑synchronous orbit, solar arrays can operate in near‑constant sunlight, reaping up to 8× the productivity of ground panels. However, energy storage inefficiencies-especially for low‑temperature systems-can dump 25% or more of generated power as waste heat. High‑temperature thermal storage or direct solar‑pumped lasers for power beaming between satellites could help cut reliance on heavy batteries while enabling dynamic load balancing across the constellation.

7. Environmental and Sustainability Considerations

While proponents tout lower terrestrial resource use, studies like Saarland University’s “Dirty Bits in Low-Earth Orbit” warn that rocket launches and atmospheric reentries could yield higher net emissions than ground data centers. Pollutants from reentry can deplete ozone, and large solar arrays may interfere with astronomical observations. Samantha Lawler notes that twilight visibility of such arrays could impact asteroid detection programs, adding a regulatory and public‑perception dimension to deployment strategies.

The convergence of radiation‑hardened AI silicon, vacuum‑optimized thermal systems, terabit optical networking, precision orbital mechanics, and falling launch costs is setting the stage for a new kind of infrastructure race‑one where compute capacity is measured not in megawatts on Earth, but in constellations of machines circling the planet. For Musk, Bezos, and Pichai, the finish line is not a single launch, but the creation of a scalable, economically viable, and environmentally defensible AI cloud in space.