Climate science just got a wake-up call: The globe’s most sophisticated models, relied on for years to steer humanity through a changing planet, tripped at the precise juncture their advice was most required. Between 2023 and 2024, Earth’s temperature surged ahead of projection, leaving scientists not only baffled, but shocked by the magnitude of the miss.

For decades, climate models have been the pillars of policy, adaptation, and risk planning. Today, a series of fresh discoveries is challenging scientists to re-examine some of their most basic assumptions. From the underappreciated strength of aerosols to the abrupt failure of carbon sinks, here are nine key findings changing the future of climate projections.

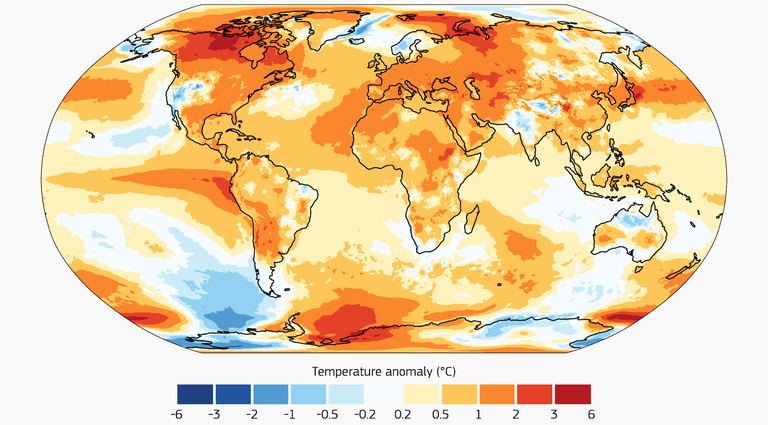

1. The 2023 Heat Spike: A Model-Breaking Surprise

The 2023 global temperature spike wasn’t a minor glitch. Rather, the world heated up 0.2°C above expectations, baffling even the best climate brains at NASA. In the words of NASA’s climate chief, “No year has bewildered climate scientists’ forecasting abilities more than 2023 has.” Land surface and sea surface temperatures both broke previous records for nine straight months, frequently by margins that, when taken at the global scale, are gigantic.

This anomaly has not dissipated for that. Rather, it has continued into 2025, contrary to the post-El Niño cooling expected to bring temperatures back on track for trend. The outcome: the climate community is unashamedly admitting to a profound knowledge gap, as the laws of the planet’s heat budget seem to be changing more rapidly than models can accommodate.

2. Aerosols: The Hidden Cooling Force

Small particles called aerosols have been known for centuries to have a cooling effect, but new studies indicate that their impact has been grossly underestimated. There are indications now that preindustrial fires emitted much more aerosols than had been thought, so the ground level of human-induced warming is higher than ever imagined.

As Cornell University’s Douglas Hamilton clarifies, “You don’t see the full effect of the warming from the greenhouse gases at any point because you also have these aerosols.” The result? As societies eliminate air pollution, the removal of this accidental cooling may speed warming far more than models have estimated.

3. Clouds: Longer-Lived, More Powerful Than Predicted

Clouds, too often written off as a modeling annoyance, have become the single largest source of error. Recent research has shown that climate models have overestimated cloud lifetimes and cooling capacity. The so-called “cloud-lifetime feedback” the mechanism through which warmer temperatures prolong cloud lifetime is found to be nearly triple the size previously estimated.

This implies clouds have lingered longer, reflecting more light and acting as a stronger buffer against warming. It’s a pivotal omission, implying both current and future warming may be more responsive to variations in cloud dynamics than thought.

4. Step-Change Theory: Climate’s Abrupt Leaps

Perhaps most alarming is that the climate of Earth is not changing gradually, but in sudden, step-like leaps. The rapid 0.25°C jump in 2023 follows a pattern observed in previous regime shifts, like the 1977–78 Pacific shift that disrupted marine ecosystems and fisheries.

Recent theory suggests that climate reacts nonlinearly to forcing, shifting between stable states in steps. This contradicts the ramp-like predictions of conventional models and portends a future with more sudden, unforeseen changes.

5. Collapse of Carbon Sinks

Forests and terrestrial ecosystems have for centuries been relied upon to mop up a substantial proportion of human carbon emissions. But in 2023, the natural buffer collapsed spectacularly. A 2024 study reported that drought and fires devastated the Amazon and Canadian forests, converting some areas from carbon sinks to net emitters.

The consequence was an 86% increase in the rate of growth of atmospheric CO₂ over the previous year. As UC Berkeley’s Trevor Keenan cautioned, “We cannot count on ecosystems to bail us out in the future.” If the trend is not reversed, the world’s carbon budget may dwindle much more rapidly than policymakers project.

6. Albedo: Earth’s Fading Reflectivity

The planet’s albedo, its capacity to reflect sunlight, has been slipping quietly, with disproportionate effects. Dr. James Hansen’s calculation equates the decrease in albedo over the recent period to an effective boost of more than 100 ppm to atmospheric CO₂. With less ice and snow come darker surfaces, which absorb more heat and enhance warming in a vicious circle.

This neglected element has amplified the Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI), driving warming above model projections and making it more challenging to limit future temperature rise.

7. The Ocean Heat Puzzle

Oceans, the Earth’s thermal reservoir, continued to take in heat at record levels, even following the end of the powerful El Niño in 2024. Greenland has lost 6,000 billion tons of ice since 2002, enough to fill Lake Superior over ten times.

Although predictions that ocean heat accumulation would decelerate, data indicate continuous warming, indicating a paradigm shift in the manner the ocean-atmosphere system is responding to external forcing. The continued imbalance is an alarm signal that the inertia of the climate system is potentially lower than previously assumed.

8. Aerosol Absorption and Precipitation: The Unseen Link

Although aerosols’ tempering of temperature is widely recognized, their effect on precipitation is less known. Black carbon and other absorbing aerosols prevent rain by heating the air and keeping clouds from forming. The 2022 study says the uncertainty over aerosol absorption is now a “key and perhaps dominating uncertainty factor in our knowledge of past precipitation change.”

What this implies is that when aerosol emissions fall, not only will the temperature increase more rapidly, but rainfall patterns, particularly in densely populated areas, may change in ways that present models are not able to accurately anticipate.

9. The Limits of Modern Climate Models

Maybe most humbling is the acknowledgment by the modeling community itself: conventional climate models have not been able to include key feedbacks from albedo modification to carbon sink failure and sudden regime shifts. Recorded warming (+1.6°C over baseline by 2024) has surpassed expectations, and uncertainty in climate sensitivity and aerosol forcing persists stubbornly high.

As the lead author of one study noted, “The fact that most of the older climate models we looked at correctly predicted following global temperatures is especially impressive considering how little observational evidence of warming scientists had in the 1970s.” Occasionally, less ambitious models with fewer assumptions have been more accurate than today’s advanced simulations.

The last two years have shown the fault lines in our knowledge of Earth’s climate machine. For climate hawks, scientists, and policy makers, the message is the same: humility and caution are required as the planet moves into unknown territory. With models being updated and fresh data streaming in, never has getting the science and the policy correct been so high-stakes. The future won’t necessarily be as a smooth curve, but as a sequence of leaps, stumbles, and surprises. Remaining vigilant to these signals will prove important in responding to the next steps of the climate.