For the first time since 1961, Russia’s human spaceflight capability has been brought to a complete and immediate stop by the collapse of a 22-tonne service platform at Baikonur’s Site 31/6 during the launch of Soyuz MS-28. The Nov. 27 incident, carrying two Roscosmos cosmonauts and one NASA astronaut en route to the ISS, has set off an extremely high-stakes engineering and geopolitical crisis.

1. Anatomy of the Failure

The mobile maintenance cabin of Site 31/6 is an enormous 144-ton steel structure measuring 19.06 by 16.92 meters. It is supposed to retract into a protected nook beneath the launch pad about an hour before liftoff, allowing technicians to access the first and second stage engines of the Soyuz rocket for final pre-launch operations, which include the installation of pyrotechnic ignition devices. Officially, the cabin retracted 44 minutes before ignition on this launch, but post-launch inspections would reveal it had either not been properly locked or the securing mechanisms failed under load as the rocket’s exhaust gases created a pressure differential that pulled the cabin from its nook, dropping it 20 meters into the flame trench and flipping it upside down.

2. Extent of Damage and Challenges of Repair

Indeed, images and drone footage reveal that the cabin is mangled beyond repair. While Roscosmos says “all necessary spare components are available,” experts point out that a replacement cabin normally takes two years to make at facilities such as Tyazhmash in Syzran. And even with spares, a full structural inspection of the pad is needed to determine collateral damage to the flame trench, support towers, and fueling lines. Estimates for restoration range from several months to three years, depending on whether a spare cabin can be installed or a new one must be fabricated.

3. Engineering Importance of Site 31/6

Baikonur’s Site 31/6 is the only pad in Russia currently certified for both Soyuz crewed launches and Progress cargo missions to the ISS. Other Soyuz-capable pads are either available at Vostochny and Plesetsk, but are unsuitable for the orbital inclination required to reach the ISS or lack certification for crewed launches. “Gagarin’s Start,” the historic Site 1/5, was retired in 2020 after its final launch and converted into a museum rapid reactivation would be difficult. This dependency creates a single point of failure in the Russian crewed spaceflight infrastructure.

4. Impact on Operations:

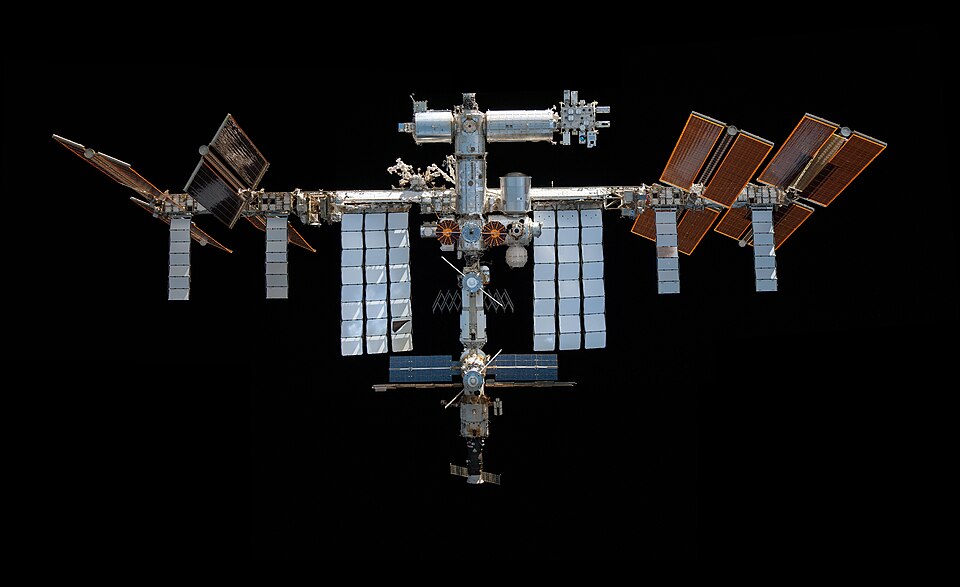

Cargo ships launched to the ISS from Site 31/6 are integral to the maintenance of the outpost. They deliver supplies, reboost the altitude of the station to counter atmospheric drag and perform “desaturation” of NASA’s control moment gyroscopes by removing excess angular momentum. While both the Dragon of SpaceX and the Cygnus of Northrop Grumman have demonstrated a reboost capability, neither is a full substitute for the integrated propulsion functions of Progress. In the absence of Russian launches, ISS attitude control and orbital maintenance would probably be more costly and operationally riskier.

5. Geopolitical and Policy Implications

The failure comes as Russia scales down its ISS commitments in preparation for its planned pullout in 2028 to dedicate resources to the Russian Orbital Service Station, or ROSS. Set to begin construction in 2027, ROSS will rely on heavy-lift launches, as well as improved crew infrastructure both of which the Baikonur incident now puts at risk. According to Jeff Manber from Voyager Technologies, “It’s a real-life test of their resilience,” since Moscow is again faced with a difficult strategic decision: heavily invest in repairs or step up its disengagement from ISS pledges.

6. Comparative Infrastructure Resilience

NASA flies crewed missions from two pads at Kennedy Space Center, creating some redundant capability between SpaceX Falcon 9 launches and future Boeing Starliner flights. Likewise, China’s Tiangong station has similar dedicated launch facilities with its Long March rockets. Meanwhile, Russia relies on a single pad to launch humans into space-a glaring liability. This incident mirrors other areas of vulnerability, such as a recent Shenzhou 20 debris strike that left astronauts stranded until a replacement craft could arrive.

7. Technical Precedents and Lessons

The R-7/Soyuz family launch pads have not been immune to major damage. For instance, a protective curtain ripped loose, and in the ensuing fall, it toppled into the flame trench of a 2016 launch from Vostochny, setting launches from there 18 months behind schedule. Events like this highlight how much crucial pre-launch verification of retractable structures and securing mechanisms is necessary, especially for legacy designs from the 1960s.

8. Contingency Paths Forward

Options range from cannibalising a maintenance cabin from an unused pad at Plesetsk to attempting to retrofit Vostochny for Progress launches. Manned launches from Vostochny feature a different set of safety problems: emergency landing zones fall in mountainous or oceanic regions incompatible with Soyuz’s land-landing design, and the pad maintenance tower cannot accommodate the Soyuz launch abort system. International sanctions also bar use of the Soyuz pad at Kourou in French Guiana.

9. Pressure on the International Partners

With Boeing’s Starliner still awaiting a successful crewed flight, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 and Dragon capsules are NASA’s only operational crew transport. The Baikonur outage could force SpaceX to shoulder additional ISS logistics, stressing its launch cadence and resource allocation. NASA has acknowledged awareness of the inspections but deferred technical details to Roscosmos, reflecting the sensitivity of the partnership amidst geopolitical tensions.

That now puts in jeopardy Russia’s next scheduled ISS launches: a Progress MS-33 cargo mission scheduled for December 2025 and a crewed Soyuz MS-29 planned for July 2006. And even if repairs proceed with dispatch, protocol dictates an uncrewed test flight before resuming human launches, making the timeline even tighter. The collapse of Baikonur’s Site 31/6 has rapidly become both an engineering emergency and a litmus test for Russia’s role in human spaceflight as the era of ISS draws to a close.