The crack in the window of Shenzhou‑20’s return capsule was barely visible in photographs. Yet simulation analysis and wind tunnel testing confirmed what China’s Manned Space Engineering Office feared: the damage, most likely caused by high‑velocity space debris, rendered the spacecraft unsafe for crewed re‑entry. Commander Chen Dong and crewmates Chen Zhongrui and Wang Jie, stranded aboard Tiangong since April, became the first Chinese astronauts to spend more than 200 consecutive days in orbit before returning aboard the newer Shenzhou‑21. The incident is a stark reminder that LEO is becoming a hazardous environment for human spaceflight.

1. Hypervelocity Impacts and Shielding Challenges

Objects in LEO have the capacity to move at 8 kilometers per second, and even millimeter‑sized pieces of debris can cause catastrophic damage. Any protection shielding attached to crewed spacecraft commonly 10–15 cm thick, composed of layers of Kevlar, carbon fiber, fiberglass, foam, and aluminum separated by air gaps serves to absorb some of the impact energy. At speeds greater than 7 km/s, debris vaporizes into molten droplets, dispersing across shield layers. Researcher Rannveig Færgestad’s work at NASA’s hypervelocity labs and Italy’s University of Padua has validated computer models with gas‑gun tests firing projectiles at such speeds, underscoring the complexity of “shock physics” in spacecraft design.

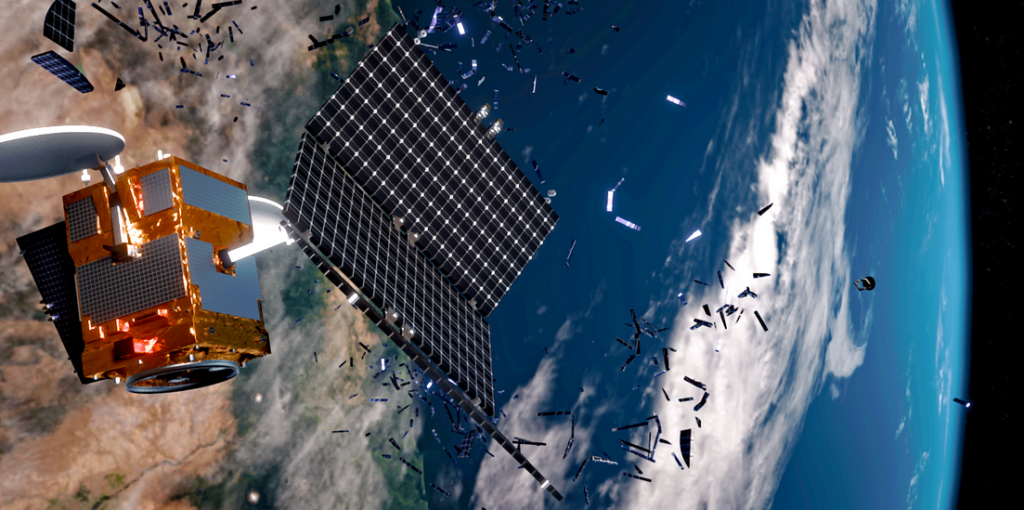

2. Orbital Congestion and Collision Risk

NASA is tracking more than 25,000 objects in orbit, but millions of fragments smaller than that remain unmonitored. In the last ten years, the number of operational satellites leaped from 1,200 to 12,000 today, and the forecast is for over 100,000 by 2040. Mega-constellations like Starlink-with more than 9,000 deployed so far-increase collision probabilities. The Kessler Syndrome could render key orbital bands unusable for decades due to a cascade of collisions generating ever-more debris.

3. Space Situational Awareness Advances

The U.S. Space Force can currently track debris only if it is larger than a softball, using its network of satellites, telescopes, and radars; 99.97 percent of the fragments are just too small. New approaches, such as the detection of radio signals by Nilton Renno, now under development, would trace microscopic debris by monitoring electromagnetic pulses produced in collisions. Coupling NOAA’s Space Weather Modeling Framework with atmospheric models could improve orbit predictions during geomagnetic storms, thus reducing spurious collision alerts and allowing for timely evasion maneuvers.

4. Active Debris Removal Technologies

Pilot missions are demonstrating debris capture and removal: Astroscale’s ADRAS‑J matched the tumbling motion of a Japanese rocket body before backing away safely while ESA’s ClearSpace‑1 will deorbit a defunct satellite in 2026. China’s Shijian‑21 has already towed a BeiDou navigation satellite to a graveyard orbit. Concepts like “just‑in‑time” collision avoidance-nudging large debris off collision paths-could offer cost‑effective remediation.

5. Innovations in Circular Space Economy and Design

Moriba Jah proposes a circular space economy of reusable, recyclable, and modular spacecraft that will produce much less trash. Along similar lines, the ESA Clean Space initiative develops “design to survive” strategies, including a Japanese prototype for a wooden satellite and inflatable decelerators to safely allow re‑entry. Incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into orbital management may encourage long‑term sustainability by paying respect to orbital carrying capacity.

6. Environmental Impacts of Space Debris Re‑entry

Burning satellites release aluminum oxide nanoparticles that can harm the ozone layer; a single 550‑lb satellite can produce 70 lbs of these particles that can stay in the stratosphere for decades. Recent research shows that re‑entering “space waste” has doubled in mass, from 366 tons in 2020 to 887 tons in 2024, with additional hazards from metals like titanium and copper. Lidar observations of lithium plumes from rocket stages confirm that re‑entry pollution is measurable and potentially significant.

7. Policy Frameworks and International Coordination

The ESA’s Zero Debris Charter and the Indian “Debris Free Space Missions” aim to reach net‑zero orbital pollution by 2030. The FCC in the United States now enforces a five‑year deorbit rule for LEO satellites and has issued fines for non‑compliance. NASA’s Space Sustainability Strategy includes emphasis on risk‑assessment frameworks prior to investing in removal technologies; and the InterAgency Space Debris Coordination Committee seeks broader membership and stronger standards.

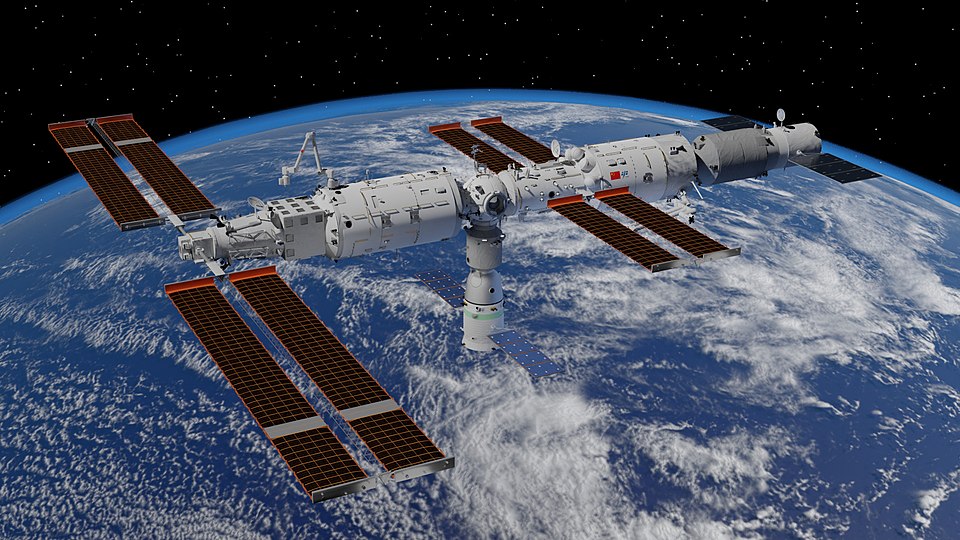

8. China’s Strategic Vulnerability

Whereas the 2007 anti‑satellite test by China remains one of the largest debris‑generating events in history, its expanding Tiangong station and the planned Guowang and Qianfan constellations make it increasingly vulnerable to orbital hazards. The Shenzhou‑20 incident may finally prompt greater Chinese engagement in bilateral or multilateral debris‑mitigation efforts, including collision notification protocols and cooperative removal missions.

The Shenzhou‑20 episode thus represents a confluence of engineering, environmental science, and policy in the challenge of orbital debris. With increasing human activity in space, protecting astronauts and their spacecraft will require not only better shielding and tracking but also unified international efforts to protect the orbital environment.”