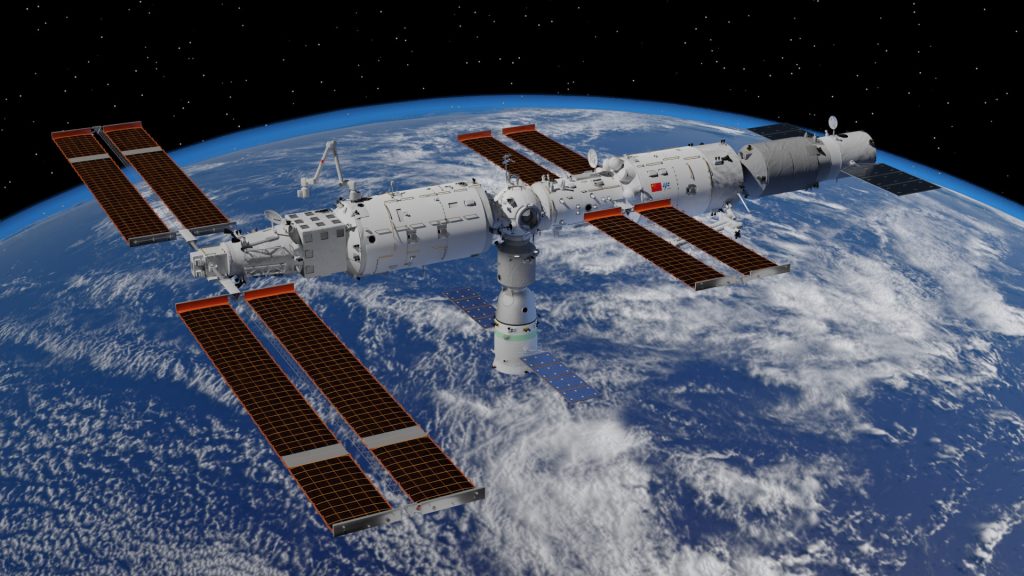

It was shaken to start not by a rocket launch but by a suspected shard of space debris slamming into the Shenzhou-20 return capsule. Three Chinese astronauts, Chen Dong, Chen Zhongrui, and Wang Jie, found themselves unexpectedly stranded aboard the Tiangong space station. The incident, occurring just hours before their scheduled Nov. 5 descent, has pushed China’s space program into a delicate balancing act: safeguarding its crew while pressing ahead with an ambitious technological roadmap aimed at putting humans on the moon by 2030.

1. The Space Debris Incident

The CMSA confirmed the Shenzhou-20 capsule “is suspected of being impacted by small space debris,” immediately delaying the return mission. Under the principle of “life first, safety first,” engineers-initiated emergency protocols to conduct risk assessments and prepare a backup capsule for retrieval. At about 180 feet long, Tiangong is designed to support two crews at once, and the stranded astronauts can carry on with in-orbit experiments with their newly arrived colleagues from Shenzhou-21. But as orbital debris specialist Darren McKnight warned, “lack of communication about events such as this hurts everyone” in the shared space environment.

2. Technical Challenges of Space Rescue

Global space rescue capabilities are still nascent. According to RAND Corporation engineer Jan Osburg, “two separate ‘stranded in space’ incidents within about a year should be a massive wake-up call” for standardized docking systems, interoperable communications, and coordinated rescue procedures. In the case of Tiangong, the presence of Shenzhou-21 provides an available safe haven, but for “free-flyer” missions without station access, rescue has to be quick because of limited life-support supplies.

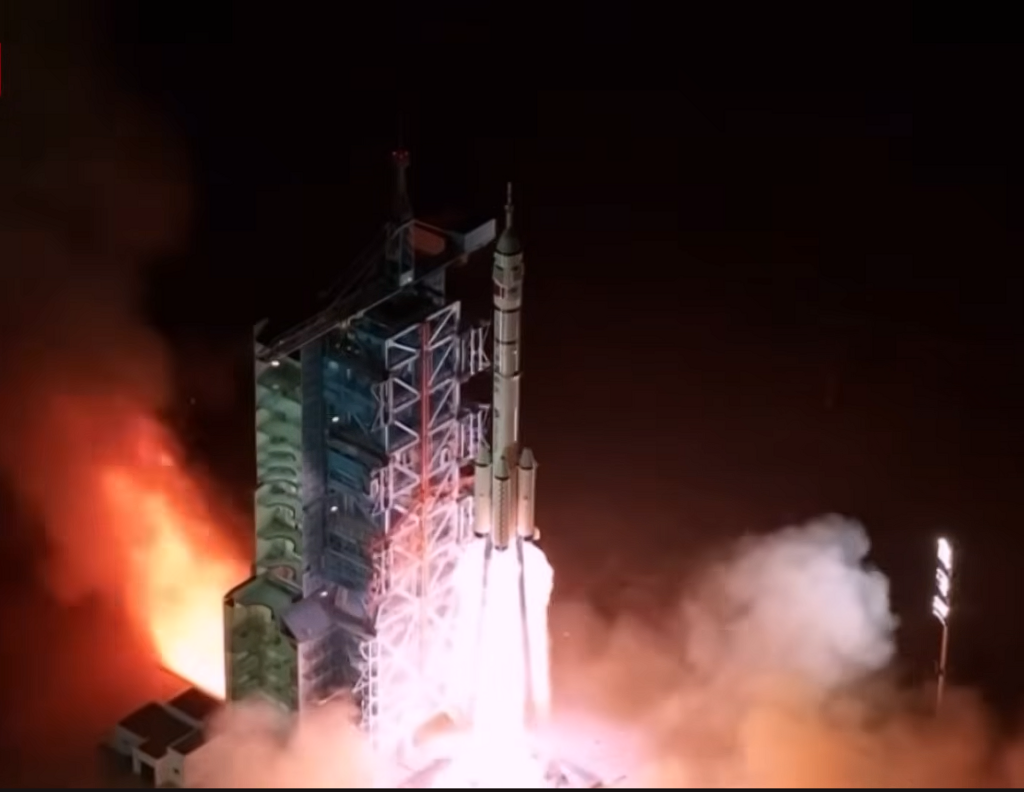

3. Long March-10: China’s Lunar Workhorse

Parallel to the rescue effort, China is also pressing ahead with the development of the Long March-10 rocket, its heavy-lift vehicle intended for manned lunar missions. The three-stage, 92.5-meter tall lunar variant will cluster three 5-meter diameter core stages, each powered by seven YF-100K engines running on liquid oxygen and kerosene. A recent ground test of a shortened first stage achieved nearly 1,000 tons of thrust, the highest in China’s spaceflight history. Four engines are fixed, while three swivel for flight control-a configuration that demands rigorous thermal and mechanical compatibility testing.

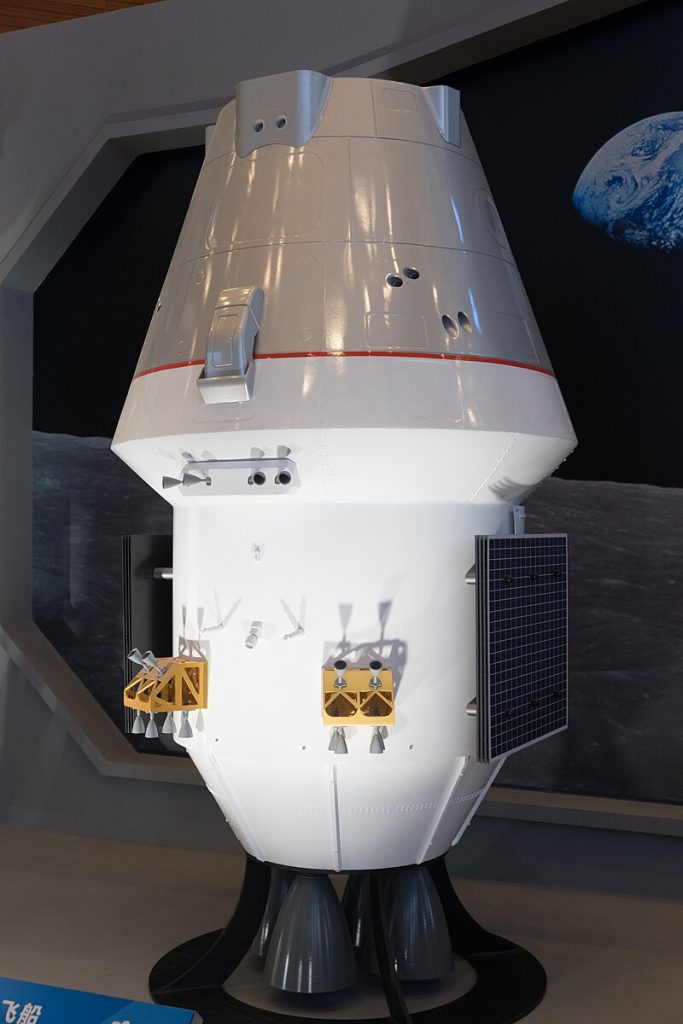

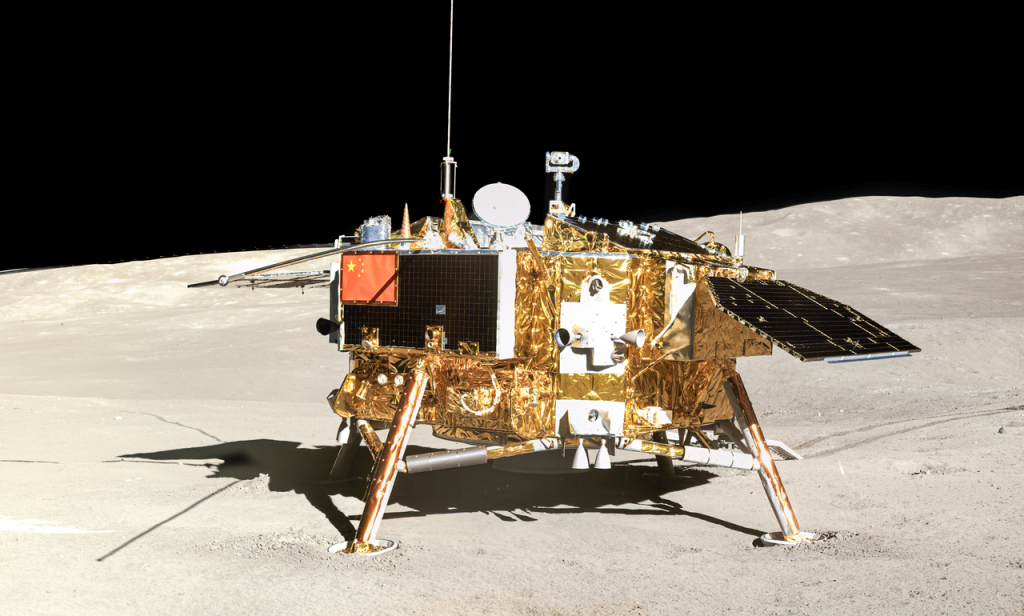

4. Mengzhou and Lanyue: Lunar Mission Architecture

The low Earth orbit and lunar variant Mengzhou crew spacecraft conducted a pad-abort test in June that showed its escape system could separate and land safely within minutes. For surface operations, the Lanyue lunar lander is designed to transport two astronauts, a rover and scientific payloads between lunar orbit and the surface. The August simulated touchdown checked propulsion, guidance and subsystem interface compatibility, and CMSA refers to it as the “lunar life center, energy center and data center” for stays on the lunar surface.

5. Innovations in Spacesuits and Rover

The newly unveiled Wangyu lunar suit by China features dust-resistant materials, thermal shielding, integrated controls, and onboard cameras that can be used for both close-up and distant imaging. The Exploration crew lunar rover is in its prototype and is being developed under a commercial competition model designed to spur private-sector innovation of mission-critical hardware.

6. Historical Roots in Deng Xiaoping’s Reforms

The fact that China is capable of undertaking such ambitious projects has its roots in the 1980s reforms under Deng Xiaoping. Strategic technologies, the subject of his Project 863, were foundational to Project 921, the manned space program now embracing Tiangong and ambitions to go to the moon. Deng’s impulse toward independent research infrastructure and high-tech industrialization transformed China’s scientific landscape, enabling today’s integrated military-civilian space sector.

7. Global Competition and Cooperation

Long March-10’s development comes against a backdrop of increased U.S.-China rivalry in space: the U.S. Artemis program aims to return humans to the Moon by 2027, while China’s 2030 plans are supported by joint ventures such as the International Lunar Research Station with Russia. Yet, geopolitical frictions-including the Wolf Amendment barring NASA-CNSA collaboration-limit direct cooperation. Despite this, China has extended offers for international participation in Tiangong and lunar sample research, echoing Cold War-era Apollo-Soyuz collaboration models.

8. Engineering Against Orbital Hazards

The shielding upgrades on Tiangong’s design come after a debris strike in 2023 damaged one of its solar panels. This is one of those very important engineering adaptations as low Earth orbit gets more crowded. A cascading chain of collisions-a so-called Kessler Syndrome-remains a near threat, a grim reminder that alongside better propulsion and habitats, technologies for debris mitigation will be required.

From rescuing stranded astronauts to accelerating hardware development for the lunar missions, China’s dual-track response captures both the fragility and resilience of human spaceflight. Every test of the Long March-10, every subsystem validation of Mengzhou and Lanyue, and every adaptation to orbital hazards brings the nation closer to a 2030 lunar landing goal-even as it navigates the rough realities of operating in Earth’s crowded orbital neighborhood.