Can a nation’s most advanced fighter jets be crippled without ever striking the assembly line? A new wave of intelligence and defense analysis suggests that Russia’s Sukhoi combat aircraft-long touted as symbols of Moscow’s military might-are far more vulnerable than their battlefield presence would suggest. Despite wartime increases in output, the elaborate web of suppliers that sustains these jets is riddled with exploitable weak points.

The RUSI has mapped a large network of approximately 1,300 companies linked to the production of Su‑30, Su‑34, Su‑35, and Su‑57 aircraft; many remain out of the scope of current sanctions, allowing Russia to circumvent restrictions through third-country intermediaries and front companies. Ukrainian strikes on some suppliers have already illustrated the potential to disrupt production, while investigative reports detail the continued flow of Western technology into Russia’s aerospace sector.

For defense analysts and strategists, these findings are more than academic. They outline concrete avenues economic, military, and diplomatic that could slow Russia’s ability to project airpower. Here are nine critical pressure points identified by recent studies and battlefield developments.

1. Persistent Dependence on Western Components

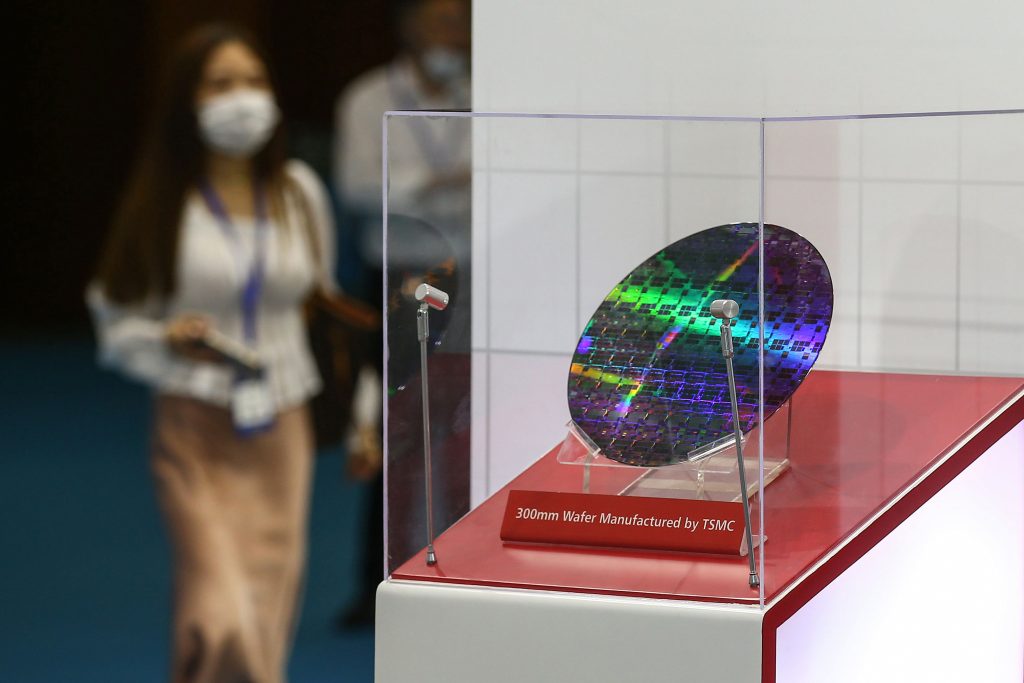

Despite years of sanctions, Sukhoi fighters in Russia still use more than 2,000 foreign-made electronic parts, many of which come from Japan and the United States. Often these products are shipped by third-country routes to get around export controls. Investigations into downed Su‑34 and Su‑35 jets revealed hundreds of U.S.‑origin microchips sourced from firms such as Analog Devices, Texas Instruments, and Intel.

2. Russia’s Microchip Dependency Exposed

The extent of dependency is remarkable: over 60% in the case of critical avionics. The consequence of this dependence thus creates a vulnerability, in that interference with such flows might degrade Russia’s capabilities over time.

Alexander Stempkovsky, founder of Alphachip, is a key figure in the chain of microelectronics supply in Russia. In July 2025, an investigation reported that Alphachip imported $2.3 million worth of U.S.-made chips in 2023, routing these chips through China, Turkey, and EU states. These parts are installed on frontline Sukhoi aircraft, directly supporting combat operations.

3. Vulnerable Second‑ and Third‑Tier Suppliers

The RUSI’s analysis underscores that the most fragile points in Russia’s aerospace network lie beyond the main assembly plants. Companies such as Skif‑M in Belgorod, which produces titanium‑processing tools, and Kulon in St. Petersburg, manufacturing ceramic capacitors, are integral to Sukhoi production.

These companies are continuing to import high‑end European equipment without restriction. To strike or sanction them could halt critical subcomponent flows, slowing final assembly.

4. Ukrainian Strikes on Industrial Nodes

Kyiv has already shown the effect of targeting suppliers. The September 2025 strike against Skif‑M disrupted its production, while attacks against Electrodetal in Bryansk, Signal in Stavropol and Aviaavtomatika in Kursk have struck at other key nodes.

More recently, Ukrainian drones damaged the Bolkhov semiconductor plant in Oryol Oblast, which makes almost 3 million devices every year for Sukhoi jets and missile systems. These moves also accord with RUSI’s recommendation for military strikes to be coordinated with economic measures.

5. Enforcement Deficit in Sanctions Regimes

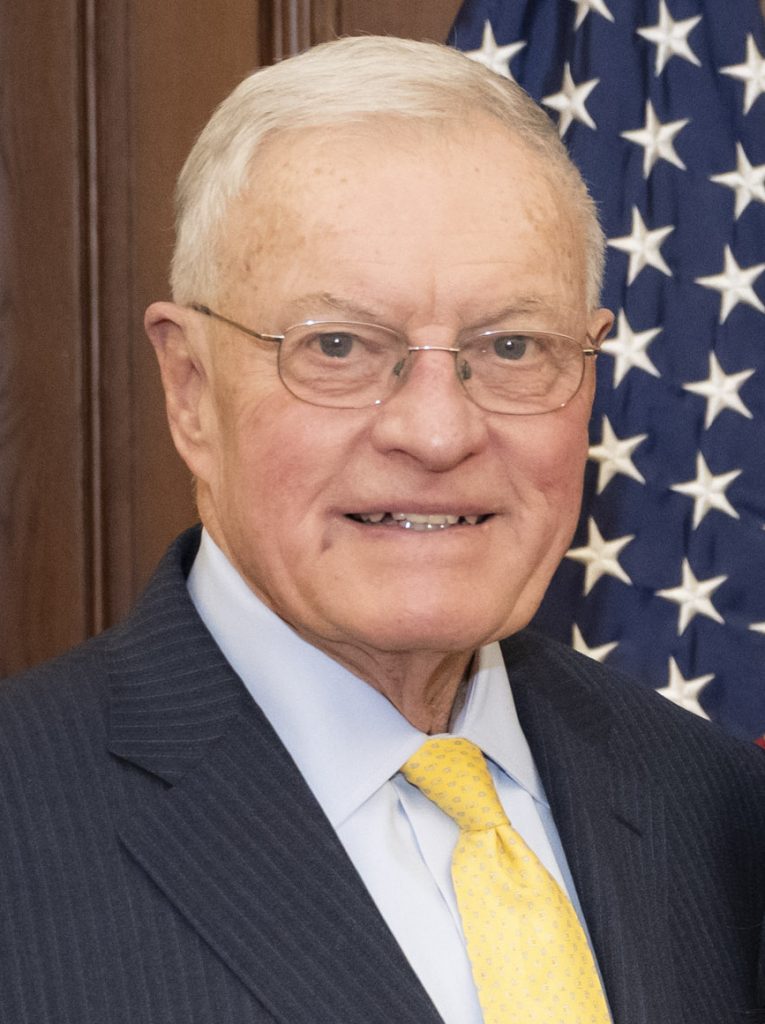

Lt. Gen. Keith Kellogg, the U.S. Special Envoy for Ukraine, has rated current sanctions design at “about a 6,” but enforcement at “only about a 3.” The problem is not just in policy but in execution monitoring and adapting to circumvention tactics requires sustained effort.

6. China’s Role in Sustaining Russia’s War Machine

Analysts say Beijing is Russia’s most important technology partner, and actively supports its military development. US-made chips bought by Chinese firms for civilian use can be diverted to Russian military systems.

Chris Miller of the American Enterprise Institute says that “90% of this problem is about Beijing’s active support.” The application of secondary sanctions or diplomatic pressure on China could greatly reduce Russia’s access to critical components.

7. Brain Drain as a Strategic Tool

Encouraging the emigration of skilled Russian aerospace engineers could erode long‑term production capacity. RUSI suggests developing pathways for these specialists to relocate, depriving Russia of the expertise needed to maintain and innovate its fighter programs.

8. Competing in Global Combat Aircraft Markets

Russia’s export market for combat aircraft is under pressure, with countries like India opting for alternatives such as France’s Rafale. Offering affordable, maintainable NATO‑aligned platforms could further displace Russian and Chinese products. This economic competition not only reduces Moscow’s revenue but also undermines its geopolitical influence in regions dependent on imported airpower.

9. Patent thicket-induced stagnation or quality reduction

Sanctions and wartime strain have forced Russia to rely on Soviet‑era designs and simplified production processes. As noted by Chatham House analysts, this leads to “innovation stagnation” and reduced quality outputs. The vulnerabilities in Russia’s Sukhoi fighter supply chain are not hypothetical-they are documented, mapped, and, in some cases, already exploited.

By expanding sanctions to overlooked suppliers, enforcing restrictions with greater rigor, coordinating strikes with economic measures, and leveraging market competition, the West can raise the cost of Russia’s airpower. The challenge lies in sustained commitment: without it, Moscow’s war machine will continue to adapt, and the opportunity to meaningfully degrade its aerospace capabilities may slip away.