The simple math is unsustainable-shoot down a $10,000 drone with a $500,000 missile, and repeat hundreds of times. But more to the point, it’s strategically perilous. A series of incidents involving Russian UAV incursions has laid bare a critical chink in the armor: NATO remains wedded to Cold War-era air defense economics on a battlefield increasingly dominated by disposable, ultra-low-cost drones. The disconnect has driven European officials to push forward expedited plans for a “drone wall” and to invest in AI-powered interceptors in hopes of catching up before low-cost aerial swarms from Moscow overwhelm defenses.

The war in Ukraine has turned into a live-fire laboratory of drone warfare, with unprecedented volumes of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or UAVs, deployed by both sides. Europe’s proximity to the conflict-and the spate of incursions over airports, military bases, and even civilian infrastructure-has made innovation in counter-drone capabilities nothing less than a matter of survival. From AI-guided kamikaze interceptors to radar systems capable of distinguishing birds from drones, the push for scalable, cost-effective solutions is reshaping NATO’s eastern flank.

1. Blaze: Latvia’s AI Kamikaze Interceptor

The Blaze, an autonomous “drone” built by the firm Origin and shown here in Riga, Latvia, embodies a new class of autonomous defense systems. Three feet tall, Blaze uses artificial intelligence to identify hostile UAVs, maneuver into close proximity, and await a human operator’s command to detonate its 28-ounce warhead. As CEO Agris Kipurs puts it: “We don’t fly these systems. These systems fly themselves.”

The design of Blaze tackles head-on the cost-to-kill imbalance. If an interception is aborted, the drone returns to base for reuse, reducing the operational cost. Already, Latvia has begun integrating Blaze into its missile defense network, using its ability to be controlled in large numbers by minimal personnel a critical advantage for a nation of less than two million citizens.

2. NATO’s Merops System on the Eastern Flank

Poland, Romania, and Denmark are fielding the US-developed Merops system – a compact AI-driven counter-drone platform small enough to be transported in a pickup truck. According to Col. Mark McLellan of NATO Allied Land Command, Merops offers “very accurate detection” and low-cost takedowns without resorting to the expense of fighter jet interceptions.

Merops works as “drones against drones,” either neutralizing targets directly or feeding targeting data to other assets. Its success on the battlefield in Ukraine drove NATO’s decision to adopt it as part of the proposed 1,850-mile-long Drone Wall intended to deter Russian incursions from Norway to Turkey.

3. Weibel Scientific’s Doppler Radar Breakthrough

North of Copenhagen, Weibel Scientific has adapted aerospace Doppler radar for drone detection. By measuring changes in signal wavelength, the system can determine a drone’s velocity and trajectory, even when it flies low enough to be mistaken for a bird.

CEO Peter Røpke said the war in Ukraine was a catalyst for demand; the company booked an order worth $76 million – the largest it has ever received. The radar capability is likely to become a “key component” of NATO’s layered drone defense, especially in defending civilian airports.

4. Startup Disruption: Frankenburg Technologies

Estonia’s Frankenburg Technologies unveiled an interceptor missile platform they said will be at least ten times less expensive than any other short-range air defense system currently available. Company CEO Krusti Salm warned of NATO’s “biggest vulnerability” in the price differential between Russian drones and Western interceptors.

Direct links with Ukrainian units enable Frankenburg’s battlefield-informed designs to rapidly adapt to emerging threats. Backed by a recent investment of €4 million, it intends to manufacture hundreds of interceptors per week-a fact which underlines the role of agile start-ups in breaking procurement inertia.

5. Lessons from Ukraine’s Drone Warfare

Moscow’s conventional firepower advantage has been offset by Ukraine’s embrace of cheap UAVs, producing millions of drones annually, to the point where the creation of the Unmanned Systems Forces in 2024 finally formalized drones as a separate military branch.

Drones now constitute up to three-quarters of Russian battlefield casualties. Ukraine’s “drone wall” along the front lines, plus naval drone strikes in the Black Sea, have shown the strategic versatility of UAVs and given both technological templates and operational doctrine to NATO.

6. Training: The Neglected Force Multiplier

As Maria Berlinska of Ukraine’s Victory Drones project said, “A drone on its own, without the coordinated work of the team, delivers nothing.” Up to 90% of success depends on operator skill, not hardware. More than thirty training centers have been certified by Ukraine, including mobile drone schools, to prepare the pilots who can double as engineers in the field. Experts such as Fedir Serdiuk warn that Europe’s focus on factories over training facilities is a “major mistake” that could undermine operational readiness.

7. Challenges in Electronic Warfare and Jamming

European firms like MyDefence build wearable RF jamming devices, but battlefield realities in Ukraine have forced adaptations. Russia deploys drones today with fiber-optic tethers or extra antennas to resist jamming. This cat-and-mouse dynamic means counter-drone systems must integrate both electronic and kinetic measures. “By definition, we will need a layered defense,” adds Ulrike Franke of the European Council on Foreign Relations.

8. Operation Eastern Sentry and the Baltic Defence Line

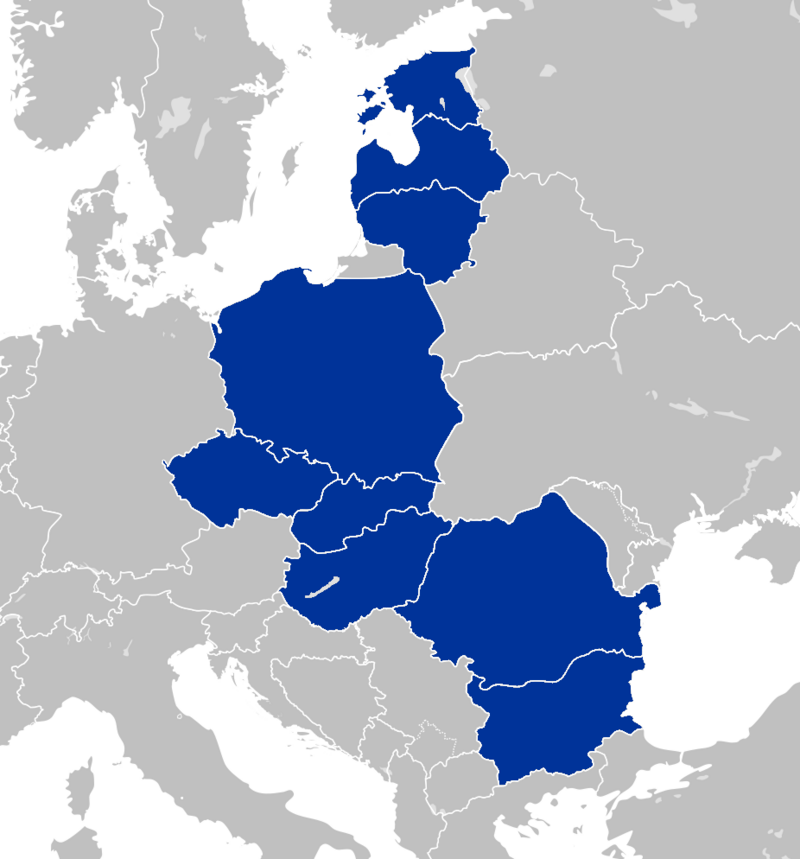

After several incursions, NATO launched Operation Eastern Sentry, combining air, land, and maritime defenses in response to the Russian drones. The so-called Baltic Defence Line between Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, and Poland’s East Shield aim to delay an onslaught while allowing time for NATO reinforcements. These projects are currently being aligned with the EU’s Eastern Flank Watch and Drone Defence Initiative, combining anti-drone systems with broader hybrid threat countermeasures.

9. The Strategic Debate: Offense vs. Defense

Some analysts say a drone wall is more about symbolic reassurance than strategic deterrence. Critics argue real deterrence, besides being able to strike back, would also require the political will to strike back against Russian drone factories and launch sites. This is echoed in Ukraine’s request for long-range cruise missiles: to stop targeting the “arrows,” but rather to disable the “archer.” The balance between defensive infrastructure and offensive capabilities will define the effectiveness of NATO’s drone strategy. Europe’s race to counter Russia’s drone threat is producing a wave of innovation, from AI-guided interceptors to radar systems and startup-led missile platforms.

But technology alone will not secure NATO’s skies. Training, cost-effective scalability, and a readiness to integrate offensive capabilities are just as crucial. The coming years will show whether the Drone Wall turns into a real shield-or just a high-tech symbol-against the evolving reality of low-cost, high-volume aerial warfare.