“Designer bags don’t win wars.” That blunt assessment by Kusti Salm, chief executive of Estonia’s Frankenburg Technologies, cuts to the heart of Europe’s looming air defense dilemma. For decades, NATO’s missile arsenals have been dominated by exquisite, high-cost systems. Now, Russia’s mass deployment of cheap drones is forcing a rethink.

In the shadow of Putin’s escalating drone campaign, a new generation of small, affordable interceptors is emerging. Chief among them is the Mark 1 a 65 cm guided missile that promises to deliver “affordable mass” against low, slow, and numerous aerial threats. The timing could be no better, because NATO’s eastern flank faces thousands of potential targets every day, and the cost-per-kill equation is tilting dangerously in Moscow’s favor.

This list looks at nine important components of Mark 1 and the wider transition to scalable, affordable air defence. Everything from the engineering trade-offs it represented to the geopolitical ramifications involved demonstrates why a missile the size of a baguette might become one of Europe’s most significant weapons.

1. A Missile Built for the Drone Age

The Mark 1 exists because Russia has normalised the mass use of one-way attack drones such as the Shahed-136. In September, NATO scrambled F-16s to intercept 20 drones over Poland, firing missiles worth around £500,000 each and failing in half the attempts. Salm calls this unsustainable, arguing that Europe needs a weapon optimised for short-range interception at a fraction of the cost.

With its range of only 2 km, the Mark 1 is designed to protect specific points rather than huge expanses of airspace. Guided by AI, it can function semi-autonomously post-launch, further reducing reliance on skilled operators a big plus since the West has a shortage of drone intercept-qualified crews.

2. Compact dimensions meet complex engineering.

At 65 cm, the Mark 1 is shorter than the average human arm. Fitting in a warhead, fuel, and sensors creates peculiar difficulties. Fuel burning away shifts the weight that can alter the tilt of a missile in mid-air, affecting accuracy. To counter this, engineers have experimented with different wing shapes, centre of gravity, and pressure distribution.

The missile’s current hit rate stands at roughly 56 % over 53 live-fire tests, with a target of 90 % as production matures. The trade-off between performance and affordability is an explicit one – the goal is to be “good enough” at scale, not perfect at boutique prices.

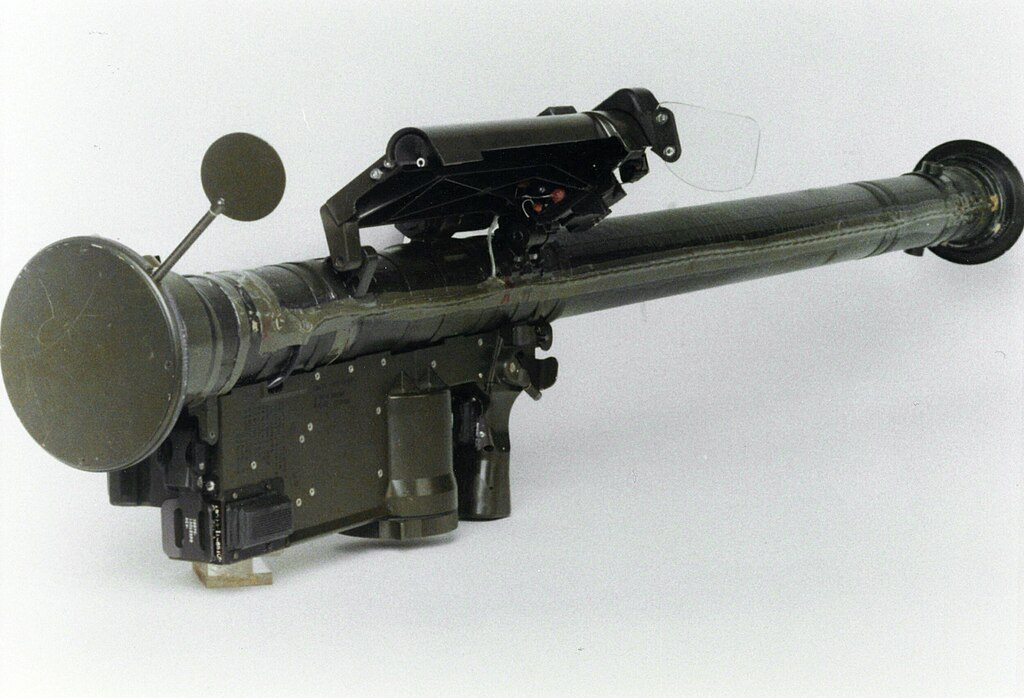

3. Cost Disruption in Air Defense

While a Stinger missile costs about £400,000, Salm says the Mark 1 comes in at less than a tenth of that. That puts it in the same affordability bracket as some low-cost counter-air programs under way in the United States, but with a sharper focus on Europe’s immediate threat.

This cost profile enables mass production hundreds per day from factories in two NATO countries and supports the “affordable mass” doctrine. What this means practically is defending thousands of critical infrastructure sites without bankrupting national budgets.

4. Top Talent on a Shoestring

Frankenburg has recruited some of Europe’s top missile engineers, including Andreas Bappert, designer of the Iris-T system, and the former chief engineer of MBDA UK’s Spear III program. Salm also credits “Latvian geniuses” with solving problems that can’t be learned from manuals.

According to Fabian Hoffmann, a missile technology analyst, there are only a few dozen people in the world who are able to bring together propulsion, guidance, and warhead systems into a working missile. And when prototypes fail, it is this rare knowledge which can make the difference between success and disaster: veterans remember obscure test results from decades ago to diagnose faults that elude younger colleagues.

5. AI Guidance and Autonomy

The Mark 1’s AI-driven guidance allows it to operate without a continuous data link, making it less vulnerable to jamming. It can track targets and intercept them independently after being launched, detonating within 1–2 m of the drone.

This autonomy further reduces operator workload, a key advantage given that Western nations lack the depth of trained drone-interceptor pilots that Ukraine has. The system can be deployed on mobile or static platforms, again adding flexibility to deployment.

6. Drone Wall Strategy of Europe

The Mark 1 is part of a layered defense concept along NATO’s eastern flank. European leaders have pledged to create a “drone wall” that combines electronic warfare, interceptor drones, and missiles. The aim is to saturate the battlespace with multiple defensive layers, forcing attackers to expend more drones for fewer results.

Within this architecture, the Mark 1 fills the short-range missile gap, fast off the rail, cheap enough to fire in volume, and accurate enough to protect key assets from low-altitude threats.

7. Lessons from Ukraine’s Drone War

The experience in Ukraine thus far demonstrates that the remedy to mass drone attacks is low-cost interceptors. Kyiv’s interceptor drones cost as little as $2,500 but require trained pilots. Western militaries do not have those pools of talent, making autonomous missiles like the Mark 1 more attractive.

Experts in Ukraine also emphasize that technology itself is not enough training and integration into broader air defense networks are needed. AI guidance of the Mark 1 partially bridges a gap in skills, but its effectiveness will depend on coordination in deployment.

8. The U.S. Parallel: CAMP and Affordable Mass

The U.S. Air Force’s Counter-Air Missile Program, or CAMP, targets a unit cost under $500,000 and production of up to 3,500 per year. Like the Mark 1, CAMP trades “exquisite” capabilities for scalability and modularity. Both efforts reflect a shift toward high-volume, lower-cost munitions to complement not replace premium systems.

This convergence suggests a transatlantic consensus: future air defense will rely on a mix of elite interceptors and mass-produced, good-enough weapons to overwhelm adversaries.

9. Strategic and Industrial Implications

By proving that a NATO-grade guided missile can be built cheaply and in volume, the Mark 1 challenges the dominance of legacy defense primes in missile production. Salm’s team is already expanding into Latvia, Lithuania, Denmark, Poland, and Germany, with UK offices opened in late 2024.

Success here might fundamentally reshape Europe’s defense industrial base and allow smaller firms to deliver frontline capabilities much more quickly. It also provides a model for other regions similarly concerned with drone saturation attacks.

The Mark 1 is no silver bullet: its range is short, its accuracy still improving, and it will work best as part of a layered defense. But its arrival signals a strategic shift: Europe is moving from relying solely on costly, limited-stock missiles to embracing scalable, affordable interceptors. In an era where adversaries can launch hundreds of drones in a night, that shift may prove decisive.