“A fighter jet is only as strong as the supply chain behind it.” That observation, echoed in recent defense analyses, captures the vulnerability at the heart of Russia’s combat aviation program. Despite decades of aerospace engineering heritage, Moscow’s Sukhoi fighters now face mounting pressure from sanctions, battlefield attrition, and a shrinking pool of skilled labor.

After almost four years of war in Ukraine, Russia’s air force has not suffered the devastating losses that its ground forces have. But its industrial base displays deep cracks. The Sukhoi design bureau, responsible for the Su-30MK, Su-34, Su-35S, and the elusive Su-57, is greatly dependent on imported components, most sourced from NATO member states or their allies. With Ukraine upping the ante and striking high-value military facilities, NATO and its partners see a window to target such dependencies with precision.

This listicle explores nine critical levers that NATO could pull to undermine the Russian ability to produce, maintain, and export its frontline fighters, drawing on a range of recent think tank reports, investigative findings, and industry data.

Targeting Second- and Third-Tier Suppliers

Sanctions against Russia’s main defense companies have already bitten, but the RUSI report emphasizes that hitting suppliers deeper in the aerospace supply chain could be decisive. Many of them deliver special machine tools, composite materials, and avionics subassemblies essential to Sukhoi production. Expanding restrictions to these lower-tier entities would enable NATO to cut links to key European sources of such equipment, forcing Moscow into costlier and less effective workarounds.

2. Disrupting Imported Microelectronics

Investigations by the International Partnership for Human Rights traced more than 1,100 foreign-sourced electronic components from downed Su-34 and Su-35S aircraft these parts originate from 141 companies in the US, Germany, Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, and are what allow for precision targeting, communication, and navigation. Cutting off access to field-programmable gate arrays and specialized microcontrollers would cripple Russia’s ability to maintain advanced combat functions.

3. Coordinating Military Strikes with Economic Measures

Already, Ukraine’s campaign against fuel depots, refineries, and chemical plants disrupts Russia’s war economy. The best way to maximize disruption would be to align these strikes with sanctions targeting aerospace facilities. The RUSI analysis points out that hitting sites that make replacement machine tools would directly slow Sukhoi assembly lines, compounding the effects of supply chain restrictions.

4. Encouraging a Brain Drain

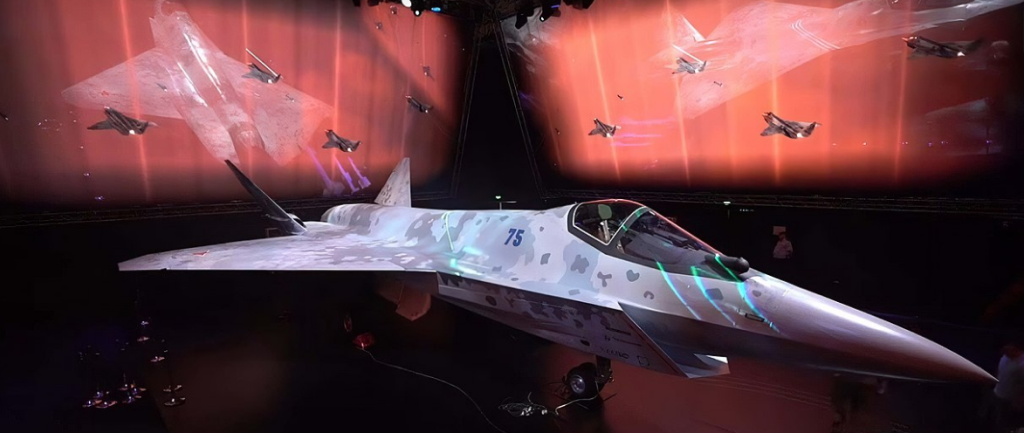

The pool of engineering talent is shrinking as mobilization pulls skilled workers to the front. The West could accelerate that trend by providing ways for aerospace engineers to emigrate. The loss of top designers and production specialists would undermine long-term projects such as the Su-75 Checkmate and PAK DA bomber, both of which are already behind schedule and over budget.

5. Exploiting Export Market Losses

Those countries that were considering buying Russian fighters like India have now looked toward NATO and Chinese alternatives. NATO could further undercut Russia’s export base by offering more competitive packages that feature greater affordability and lower maintenance profiles. Reduced foreign sales result in less money to reinvest in domestic production, weakening the sustainability of the Sukhoi program.

6. Tightening Controls on Gray-Market Routes

Despite these sanctions, Russia has imported over $1 billion worth of Western aircraft components since 2022, increasingly via third countries. The most popular routes go via China, Hong Kong, Turkey, and the UAE. Tightened monitoring and enforcement along these corridors could choke off the fragmented, low-value shipments that have been designed to evade detection, as documented in IPHR’s shipment tracking analysis.

7. Amplifying Reliability Concerns

Questioning the operational reliability of Sukhoi fighters could have disproportionate consequences on the export market. Publicizing incidents linked to outdated or substitute components, such as the fatal crash of a 1972-built Antonov An-24, would add to the perception that Russian aircraft are unsafe and discourage foreign militaries from procuring them.

8. Leveraging Oil Price Pressures

Russia’s defense budget is deeply reliant on hydrocarbon revenues, and crude is down 18% so far this year. Continued economic pressure in energy markets would make the Kremlin triage spending between its military branches and potentially put expensive fighter programs on the backburner to meet battlefield needs.

9. Inhibiting Production Capacity

According to Ch-Aviation, Russia’s aviation industry produced just one aircraft in 2024, against a target of 15. Shortages of parts, technology, and skilled labor have idled production lines. NATO could exploit this fragility by reinforcing sanctions on industrial inputs and promoting inefficiencies in Russia’s dispersed Soviet-era factory network. Russia’s Sukhoi fighters are still formidable battlefield assets, but their very survival depends on a tenuous web of imported components, skilled labor, and export revenues.

By integrating economic, military, and diplomatic instruments, NATO can systematically destroy the industrial base for Moscow’s air power. The strategies proposed in this essay will not yield immediate returns-but steady pressure might just guarantee that Russia’s newest jets never achieve the numbers or capabilities planned by those who designed them.