Nuclear testing can never be permitted under any circumstance. This was no abstract warning from the United Nations this week; it came as Moscow unveiled a weapon which many experts believe could rewrite the rules of nuclear deterrence. Confirmation from Russia of a successful test of the nuclear-powered torpedo Poseidon has added new urgency to fraught debates on arms control, strategic stability, and the legality of certain weapons under international law.

This is the latest in a series of military escalations, including US calls to resume nuclear weapons testing, increased strikes by the Russians on Ukraine’s energy grid, and the deployment of new delivery systems that can carry nuclear weapons. For defence analysts and policymakers, it’s not about hardware alone, but the shifting thresholds of nuclear use, the erosion of long-standing treaties, and embedded geopolitical signalling with each test.

The following list takes stock of the most consequential elements driving this standoff, from the technical capabilities of Poseidon and Burevestnik to the legal and strategic implications of deployment and the risks of miscalculation in an already volatile theatre.

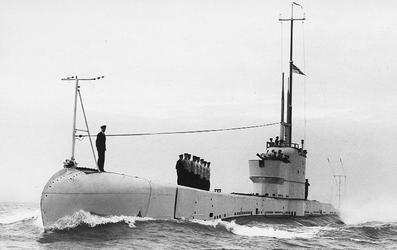

1. Unique Design and Functionality of Poseidon

The Poseidon differs from every other nuclear delivery system: an autonomous, nuclear-powered undersea drone that first came into the public eye in 2015 and which would be fitted with a multi-megaton warhead. Russia claims it will be able to travel at 70 to 100 knots with operations down to 1,000 meters depth and intercontinental range. Its mission profile would be clear: detonation offshore to generate a radioactive tsunami capable of rendering coastal cities uninhabitable.

According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the weapon’s compact reactor is “100 times smaller” than those on submarines, yet its warhead yield could exceed that of Russia’s Sarmat ICBM. Were such a system to work, it would sidestep traditional missile defenses altogether. Yet its possible autonomy significantly increases its risks of loss of control, cyber interference, or environmental triggers leading to unintended escalations.

2. The Burevestnik: A Flying Reactor with Global Reach

The Burevestnik cruise missile, tested days before Poseidon and codenamed “Skyfall” by NATO, similarly uses a nuclear reactor to sustain flight over potentially unlimited ranges. One recent trial, announced by Russian General Valery Gerasimov, reportedly covered 14,000 km in 15 hours with complex manoeuvres performed to evade defences.

Analysts in the West are more sceptical. The International Institute for Strategic Studies has pointed to repeated test failures, including a 2019 accident in the Arctic in which five scientists were killed and radiation was released. Critics say its strategic value is limited given Russia’s existing arsenal of ICBMs, and that the environmental risks of a reactor-powered missile overflying populated areas are unacceptably high.

3. Legal Questions Over Weaponised Tsunamis

International law proscribes various means and methods of warfare, and the concept of operations for the Poseidon could violate those prohibitions. The ENMOD Convention prohibits uses of environmental modification techniques having widespread, long-lasting, or severe effects; Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions prohibits methods of warfare expected to cause such damage to the natural environment.

A detonation intended to cause a radioactive tsunami would, by intentionally distorting natural processes, disregard the principle of distinction in targeting civilian objects and personnel, and military ones alike. Among other things, this makes Poseidon likely unlawful per se under the law of armed conflict, according to a number of legal scholars including former U.S. Navy Captain Raul Pedrozo.

4. Strategic Signalling and Nuclear Brinkmanship

The timing by Putin-testing two new nuclear-capable systems in quick succession-has been read as coercive signalling. Dani Belo of the Norman Paterson School of International Affairs called it “saber rattling” intended to emphasize Russia’s first-strike credibility and dissuade the West from further escalation.

These tests coincided with the meeting of US President Donald Trump with Chinese President Xi Jinping, suggesting an audience beyond Ukraine. As Janice Stein has argued, such moves fit the pattern of “the threat that leaves something to chance,” a strategy designed to manipulate risk when facing potential strategic loss.

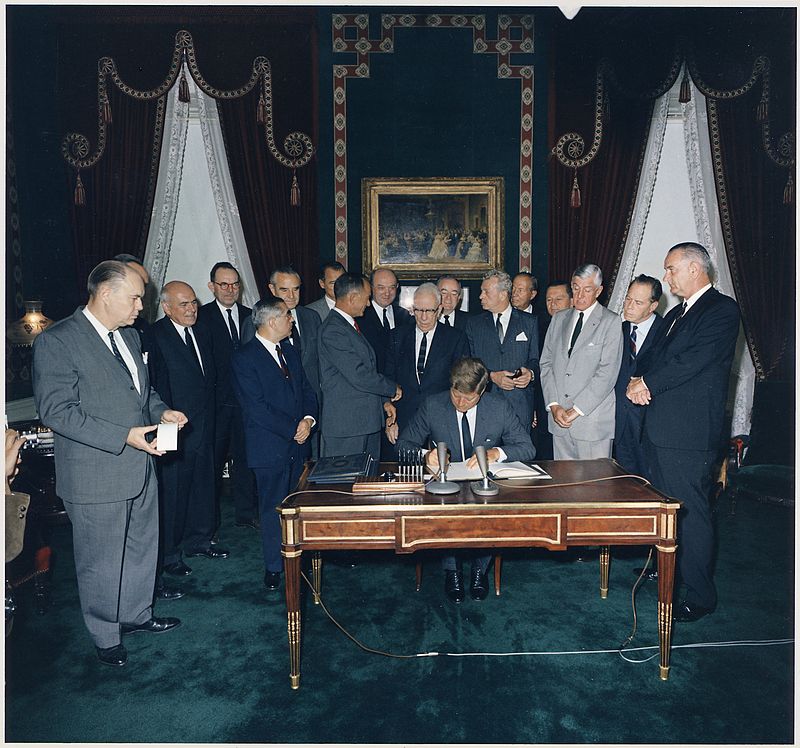

5. US Response: Calls to Resume Nuclear Testing

Trump’s instruction to “start testing our Nuclear Weapons on an equal basis” is a radical break with a three-decade moratorium. The last time an explosive nuclear test was carried out by the U.S. was in 1992. Since that time, the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty has been signed by 187 states, although not ratified by Washington.

Experts warn, however, that any resumption of testing would be matched by Russia and China, eroding the nonproliferation regime even more. According to the National Nuclear Security Administration, it would take 36 months to prepare the Nevada site for underground testing-a gap between rhetoric and capability.

6. Escalation Risks and Miscalculation

Although the chances of a nuclear weapon being used in Ukraine remain low, analysts suggest that Russia has lowered its doctrinal threshold for nuclear use. A November 2024 decree allows for nuclear strikes against non-nuclear states attacking Russia or its allies if those states are backed by a nuclear power.

Battlefield reversals, the assassinations of high-profile individuals, and mass civilian casualties are but a few scenarios that could theoretically consider tactical nuclear use. Yet, as Stein points out, context matters: so far, Putin has favored conventional escalation over breaking the nuclear taboo, lest he alienate partners such as China and India.

7. Russian Strikes on Ukraine’s Energy Grid

In October, three major Russian attacks targeted thermal power plants in Ukraine, damaging critical equipment and forcing the country into nationwide electricity rationing. Privately operated DTEK reported this month’s strikes as the most severe since a full-scale invasion began. Besides the humanitarian consequences, such attacks also send ripples through European energy markets: sustained targeting of Ukrainian gas production could create regional deficits, pushing prices higher and testing EU solidarity, warn energy analysts.

8. Arctic Buildup and Nuclear Posture

Norway’s defence minister has confirmed increased Russian weapons development on the Kola Peninsula, which hosts one of the world’s largest nuclear stockpiles. Submarines capable of deploying Poseidon will also form part of expanding the Northern Fleet.

The implication is clear: this Arctic concentration not only imperils NATO’s northern flank but also complicates arms control verification; it points to Moscow’s intention to introduce new systems into its strategic deterrent, probably outside existing treaty frameworks.

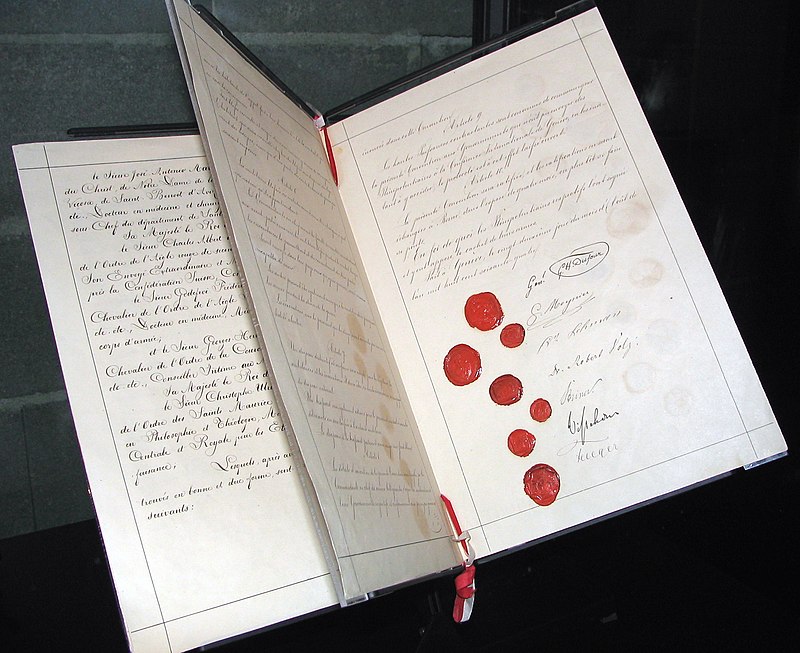

9. The Erosion of Arms Control Frameworks

The New START treaty, capping deployed strategic warheads at 1,550 per side, expires in February 2026. With Russia’s suspension of participation and U.S. attention turned toward China’s buildup, prospects for renewal are dim.

Deployments falling outside traditional categories-like those of Poseidon and Burevestnik-further undermine verification regimes. Without new agreements, the strategic environment will continue to slide toward a multi-polar arms race with fewer guardrails than at any point since the Cold War.

The test of Poseidon is more than a technical milestone-a geopolitical signal, a legal provocation, and a potential accelerant in the new nuclear arms race. With both Washington and Moscow flirting with breaching long-standing testing taboos, and with novel systems blurring the lines of deterrence doctrine, the margin for error is narrowing. It presents a challenge to policymakers to respond to each capability in isolation but also to recognize the cumulative erosion of norms that has kept nuclear weapons unused for nearly eight decades.