Why would Moscow risk alienating its largest arms customer for a far smaller, less reliable market? This is the question that has been raised once again in India’s strategic circles amidst the raging controversy over Russia’s supply of RD-93MA jet engines to Pakistan’s JF-17 Block III fighters. Deliveries, notwithstanding objections from New Delhi, have become a political flashpoint with opposition leaders framing them as evidence of diplomatic failure and erosion of India’s leverage over a traditional partner.

While optics may suggest a shift in Russia’s South Asia calculus, reality is far more complex: Moscow’s defense engagement with Islamabad has remained very limited, constrained by the market dominance of India and the financial fragility of Pakistan. Yet, the persistence of these ties-from selective arms sales to joint military drills-deserves closer scrutiny of the drivers, constraints, and strategic calculus underpinning them.

1. Engines at the Core of Controversy

The new RD-93MA is an improved derivative of the RD-93, itself a Russian adaptation of the RD-33 used on MiG-29s. It develops 9,300 kg of thrust from the earlier 8,300 kg. It is installed on the JF-17 Block III, which allows heavier payloads, state-of-the-art avionics, and higher speeds. Pakistan selected this Russian powerplant for its reliability over China’s WS-13. The latter had a number of performance issues that made it unsuitable for front-line service.

Russia has supplied more than 200 RD-93 engines to Pakistan since 2007, according to SIPRI’s data-most of them through China as part of a re-export agreement. The recent direct deliveries are significant but do not involve the transfer of technology. In the opinion of Pyotr Topychkanov, a Russian defence analyst, “It shows that China and Pakistan haven’t yet managed to replace the Russian-origin engine the new aircraft will be familiar and predictable to India.” According to some, this familiarity reduces operational uncertainty for New Delhi.

2. Historical Limits on Arms Sales

Caution over arming Pakistan had been Moscow’s policy since the 1990s, when a proposed Su-27 sale was abandoned under Indian pressure. Since then, for decades, Russia restricted itself to supplying dual-use Mi-17/171 transport helicopters and a few Mi-35M gunships. This reluctance was due to the fear of losing access to the far larger defence market in India.

Even when the Pakistani requests included such items as air-to-air missiles, tanks, and frigates, most proposals were held up. The public reassurance by the leadership, including from Vladimir Putin in 2010, that Russia would not pursue military-technical cooperation with Pakistan “taking into account the concerns of [our] Indian partners,” further reinforced this self-imposed restraint.

3. Pakistan’s Purchasing Constraints

Estimates by Russian analysts in 2019 set the aggregate demand of Pakistan for Russian arms at US$8–9 billion, but such figures are unrealistic given Islamabad’s chronic economic weakness and dependence on IMF bailouts and Chinese military aid. Large-scale deals would require Russian loans a prospect unappealing to Moscow at a time when it too needs hard currency.

The financial fragility of Pakistan constrains its ability to convert political goodwill into serious procurement. The nature of defence cooperation has remained confined to niche supplies and training rather than transformational acquisition.

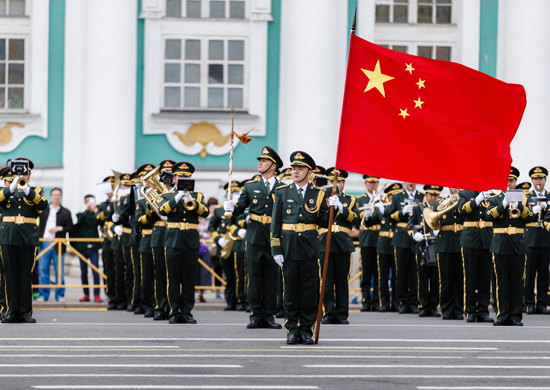

4. Joint Military Exercises as Strategic Signalling

The Druzhba counter-terrorism exercises have alternated between Russia and Pakistan since 2016, with a focus on urban combat and counter-IED tactics. More recently, they also include drone warfare. Such September 2025 drills in the Southern Military District of Russia included scenarios reflecting the recent regional conflicts, among them the May 2025 clash between India and Pakistan, where unmanned systems had played a major role. Such exercises on land are supplemented by naval cooperation in the form of the series named Arabian Monsoon, further enhancing interoperability in maritime security. These are both operational exchanges and geopolitical signals that Moscow maintains defense channels with Islamabad, notwithstanding Indian sensitivities.

5. India’s Enduring Leverage

It is estimated that India remains Russia’s biggest arms customer, and about 60 percent of its military inventory is of Soviet or Russian origin. This ranges from tanks and artillery to aircraft and submarines, with even joint projects like the BrahMos missile. The stakes grow higher with high-value negotiations for additional S-400 systems, possible S-500 co-production, and Su-57 fighters. Given this scale, Moscow is unlikely to jeopardize billions of dollars in Indian contracts for the modest Pakistani deals. The RD-93MA episode underlines the tightrope that Russia walks in maintaining limited engagement with Islamabad while protecting its strategic and commercial partnership with New Delhi.

6. Afghanistan as a Converging and Diverging Arena

Russia’s overtures to Pakistan have more often than not been linked to Afghan security. The two sides have coordinated on counterterrorism and have opposed Western military bases in the region. Formats like the ‘extended troika’-US, Russia, China, Pakistan-recognised Islamabad’s influence over Afghan dynamics. Yet differences persist. Moscow’s April 2025 removal of the Taliban from its terrorist list troubled Pakistan, which faces cross-border attacks from the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan. These divergences could limit deeper strategic alignment, even as Afghanistan remains a shared security concern.

7. Optics Versus Reality

While the RD-93MA supply is projected as a strategic setback by political reactions in India, such as Congress leader Jairam Ramesh’s criticism of “personalised diplomacy,” the reality is that Russian engagement with Pakistan is actually constrained by economic pragmatism and the overriding priority of its Indian partnership. While the optics of joint drills and engine deliveries may serve Moscow’s signalling purposes reminding New Delhi of its options they stop short of altering the fundamental balance of Russia’s South Asia policy.

While symbolically potent, Russia’s defense cooperation with Pakistan remains strategically limited. The RD-93MA deliveries serve to underline Moscow’s readiness to engage Islamabad within carefully managed boundaries, balancing geopolitical signaling with economic self-interest. For India, the challenge lies not so much in the scale of these transactions but in interpreting their intent-and in ensuring its own leverage over Russia remains intact in shifting regional currents.