Can a decades-old air defense concept suddenly become relevant in the age of drone saturation? The answer may be yes, if indications of Russia’s revival of the 42S6 “Morpheus” short-range system are anything to go by-this time around as a containerized, stationary launcher. Over the past months, imagery and expert analyses have indeed pointed to a fixed vertical-launch module, housed in a shipping-style container, capable of holding up to 16 missiles. This is a decidedly stripped-down, modular approach that sharply breaks with the original vehicle-mounted design and meets a growing need for scalable, cost-effective point defense against massed loitering munitions.

The timing is no coincidence. Since 2022, the explosive rise in low-cost attack drones, particularly Russia’s Shahed series, has forced militaries to rethink layered defense. Systems like NASAMS have proved highly effective but remain expensive to field widely. A containerized Morpheus could fill gaps by defending fixed rear-area targets-energy infrastructure, command nodes, and urban centers-without the logistical footprint of a full mobile battery. Below are seven key aspects of this revival that matter to defense analysts tracking Russia’s evolving air defense strategy.

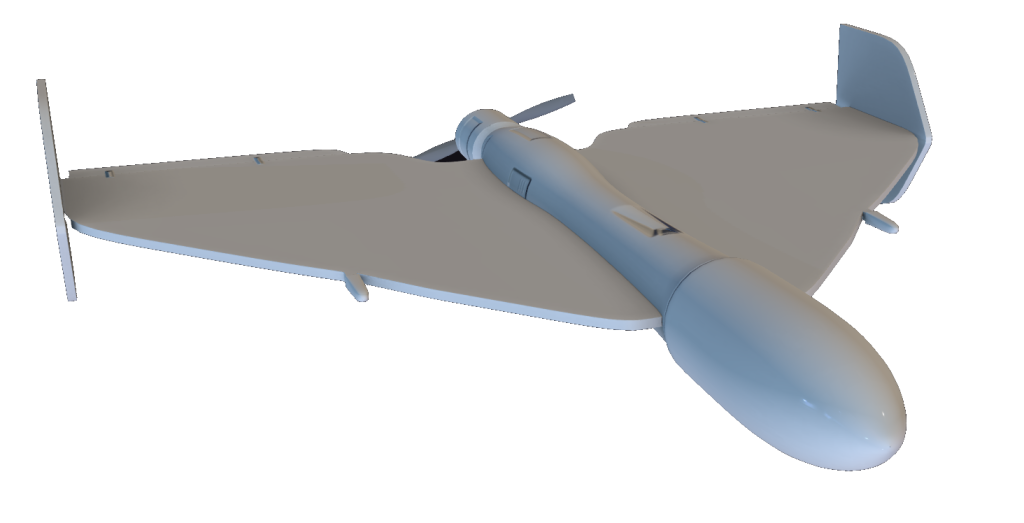

1. From Mobile Chassis to Containerised Launchers

The original Morpheus concept that began in 2007 called for BAZ-69092 chassis vehicles with integrated radar, optical targeting, and a 24-round launcher. That was supposed to provide close-range protection for higher-tier systems such as the S-400 and S-500. The new variant has ditched mobility in favor of a shipping-container format. Each unit seems to be self-contained, with missile racks, an internal generator, and remote-control electronics, but no onboard radar. It’s similar to how dispersed architectures work in NASAMS, where sensors and launchers are separated to minimize vulnerability.

By housing the launchers in transportable containers, operators can reposition them by truck yet keep them stationary during operation. This configuration supports flexible deployment whereby launchers can be scattered around critical sites while central radars feed targeting data over several kilometers. The lack of organic sensors further reduces cost and complexity to allow mass production and rapid fielding.

2. The Imperative of Drone Saturation

The Russian Shahed drone campaign has demonstrated well the strain that low-cost UAVs can place on high-end air defenses. At $20,000-$50,000 per Shahed, Moscow can tolerate high attrition rates to exhaust Ukrainian interceptors, which run into hundreds of thousands per shot. This attrition logic is forcing defenders to pursue economical countermeasures. Renewed interest in Morpheus reflects this environment: a short-range, containerized system could provide a cheaper shield against waves of drones targeting rear-area assets.

According to analysts at Defense Express, since late 2024, Russia has increased Shahed launches from 200 per week to more than 1,000 by March 2025. Such volumes demand point-defense solutions that can be widely dispersed without the expense of full mobile batteries.

3. Possible Missile Choices and Capabilities

The missile type for the revived Morpheus is not confirmed. Online commentary identifies the 9M338K developed for the Tor-M2 as the likely candidate. This missile provides engagement ranges out to 16 km and altitudes to 10 km, twice the capacity of older Tor variants. The smaller size enables 16 rounds per launcher, matching the apparent loadout of the container.

Earlier Morpheus specifications were more modest: about 6 km of range and 3.5 km of altitude, optimized for ultra-low altitude threats. Whether Russia opts for the longer-reach 9M338K or retains a short-range round will signal its intended role-either as a broader counter-UAV layer or a last-ditch defense against drones and precision-guided munitions.

4. Separation of Sensors and Shooters

Publicly available images do not show any radar or command post integrated into the container. Instead, sensors will be set several kilometers away from it, controlling launchers remotely. Such separation allows operators to disperse launchers without duplicated expensive radar units and increases survivability against anti-radiation strikes.

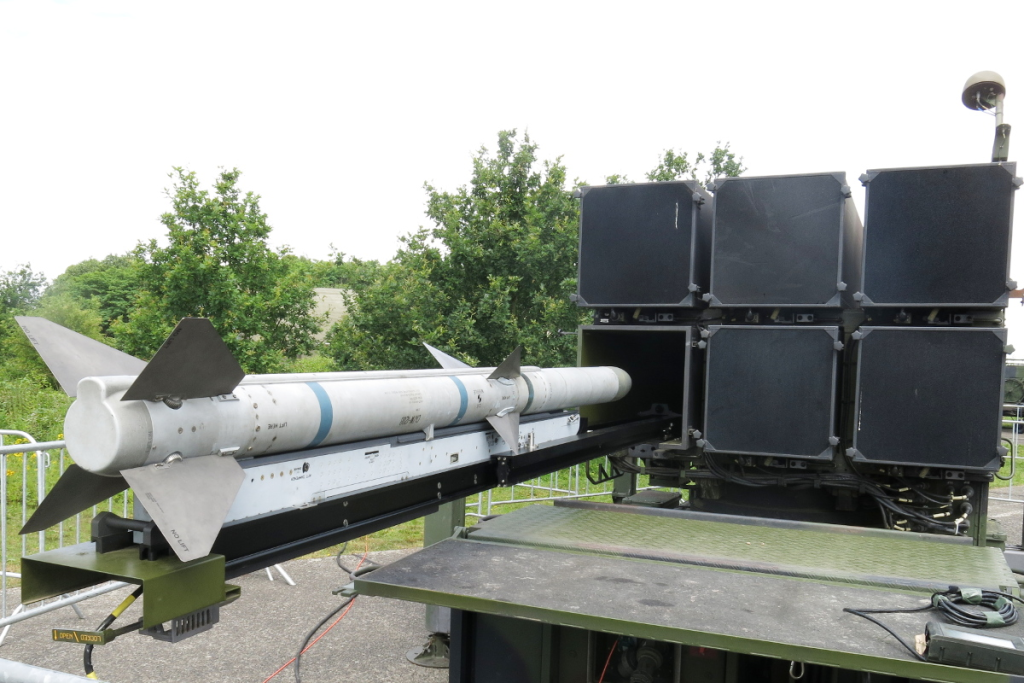

One central radar or command post can thereby control several widely dispersed and separated launchers, creating a networked defense grid. Another similar model is the NASAMS system, which integrates the AIM-120 AMRAAM missiles in conjunction with Sentinel radars and a command-and-control network; thus, a high intercept rate can be realized with flexibility in deployment.

5. Lessons from the NASAMS Deployment in Ukraine

The experience of Ukraine with NASAMS has underlined the importance of multi-layered, modular defense. At least three NASAMS batteries, each with a set of several launchers and radars, arrived at the beginning of 2025. The system has a 94% success rate, shooting down 900 aerial threats, over 500 of which were cruise missiles, according to Colonel Trøite. The ability of NASAMS to integrate with other systems and defend multiple sites simultaneously provides something of a blueprint for Morpheus. A containerized launcher network, tied into existing Russian radar infrastructure, would offer similar flexibility albeit with a very different missile technology and engagement envelope.

6. Countering Evolving UAV Threats

Russian UAV tactics have become increasingly sophisticated, from fiber optic-carrying drones impervious to electronic warfare to thermobaric warheads set against fortified positions, as well as sleeper drones capable of striking with minimal warning. These innovations have extended the depth of the “kill zone” out to up to 10 km from the front line, and allowed interdiction of Ukrainian ground lines of communication well into the rear. A containerized Morpheus would, if equipped with missiles capable of engaging small, maneuvering UAVs, be able to provide a static countermeasure against such threats. Its fixed deployment would be well-suited for the defense of infrastructure nodes where persistent UAV harassment is likely.

7. Strategic Implications of Mass-Fieldable Point Defense

The revival of Morpheus in container form signals Russia’s intent to field a lower-cost, mass-deployable air defence layer. By stripping out mobility and organic sensors, the system becomes cheaper to produce and easier to deploy en masse. Such an approach could blanket critical rear-area sites with short-range defences, freeing higher-tier systems to concentrate on long-range threats. For defence planners, the concept raises questions of scalability, integration with existing networks, and resilience in the face of saturation attacks. If it proves out, it may mark a shift toward modular, distributed air defence architectures designed to survive in an age of cheap, numerous aerial threats.

The containerised Morpheus is more than a hardware update; it is a doctrinal adaptation to the realities of drone-era warfare. Dispersed deployment, centralised sensing, and possibly versatile missile options: here, Russia experiments with ways of countering the economic and operational pressures of saturation attacks. Whether this revival will yield meaningful capability depends on integration, scale of production, and the missiles that are chosen. For analysts, it offers a case study in how legacy projects can be reimagined to meet the demands of modern conflict.