The seizing of the Benin-flagged oil tanker Boracay off France’s Atlantic seaboard has brought Russia’s “shadow fleet” illegal oil trading operations into sharp relief. French President Emmanuel Macron confirmed the ship’s connection to blacklisted Russian oil activities and accused its sailors of “extremely serious crimes.” The seizure, which was conducted by French naval forces at prosecutors’ request, forms part of a larger European drive to interfere with a group of ships that cheat sanctions, conceal ownership, and serve, in some instances, as a hybrid warfare platform.

1. The Ship and Its Suspicious Journey

Constructed in 2007 and also referred to as Pushpa and Kiwala, the Boracay left the Russian port of Primorsk on September 20 for Vadinar, India. Its itinerary took it past Denmark during September 22–25 dates which coincided with unexplained drone intrusions into airports and military facilities. Marine Traffic records show that the tanker changed course off Brittany, accompanied by a French warship, before anchoring off Saint‑Nazaire. Brest prosecutors have brought charges against the crew for “failure to explain the nationality of the vessel” and “refusal to assist,” highlighting the mysterious registry practices that are characteristic of shadow fleet operations.

2. Anatomy of the Shadow Fleet

Macron puts Russia’s shadow fleet at between 600 and 1,000 vessels, raking in “tens of billions of euros” and paying for about 40% of Russia’s war effort. These ships are largely aging tankers tending to be more than 20 years old purchased using shell companies in jurisdictions that do not sanction sanctions. They operate under flags of convenience of countries like Benin, Gabon, and Palau, without access to reputable insurers or port inspections. Ownership is deliberately kept hidden research indicates 44% of shadow ships have changed owners or managers three or more times within a year.

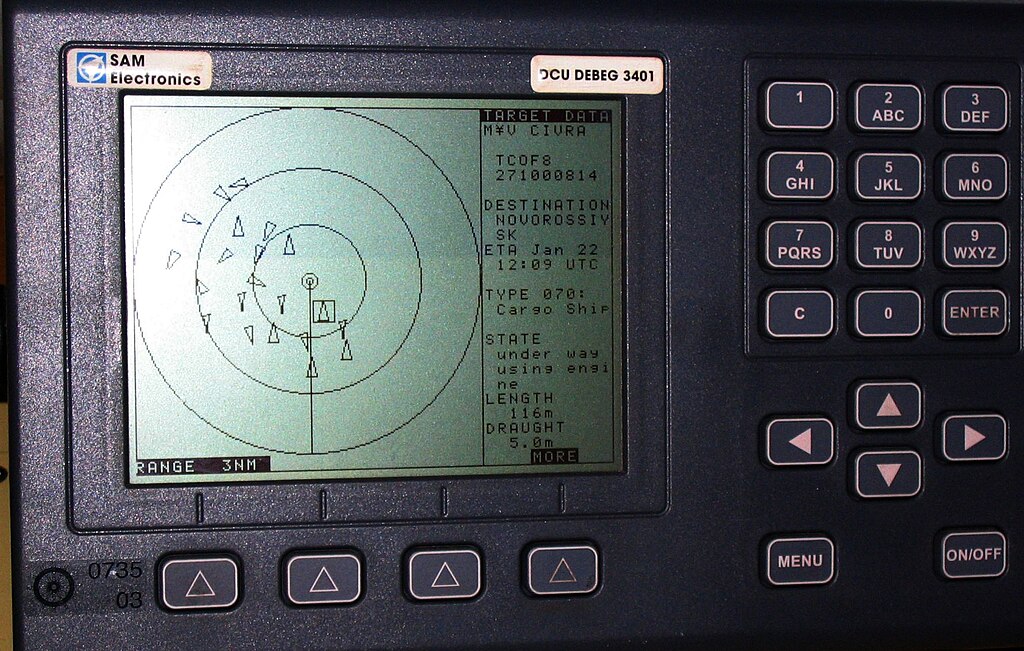

3. AIS Manipulation and Tracking Countermeasures

One characteristic of shadow fleet navigation is the jamming or silencing of Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponders, which are required for collision avoidance. Some ships spoof AIS signals to pretend to be other ships, and this tactic is matched by Russian naval escorts like the missile‑equipped corvette Boikiy. Detection is becoming more dependent on synthetic aperture radar and thermal imaging satellites, which can detect a ship’s steel hull outline even when AIS is off. Maritime AI companies such as Windward have reported that a fourth of wet‑cargo ships now travel beyond the official tracking system.

4. Hybrid Warfare at Sea

Boracay’s appearance off Denmark in the September drone incidents mirrors historic cases when shadow fleet tankers were alleged to be involved in sabotage. On Christmas Day 2024, the Eagle S reportedly cut Finland’s Estlink 2 seabed power cable, triggering NATO’s “Baltic Sentry” operation to protect seabed infrastructure. Intelligence evaluations caution that tankers can be launch platforms for surveillance drones, carry out surveillance devices, or be used as decoys to conceal military maneuvers.

5. Engineering Undersea Infrastructure Vulnerabilities

Seabed cables and pipelines are designed with armoured sheathing and burial depths to resist fishing gear and anchors, but not deliberate interference. A tanker’s dragged anchor can shear fibre‑optic cores or crush high‑voltage conductors, as occurred in the Estlink 2 case, which cost €60 million to repair. Identifying faults involves having specially equipped cable ships with remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to perform deepwater splicing a week‑long process that interrupts national grids.

6. Environmental and Safety Risks

Shadow fleet tankers tend to be in bad condition, which enhances the likelihood of hull rust, engine breakdown, and unstable cargo accidents. The 2023 blast of the Gabon-flagged Pablo off Malaysia illustrated the risks the lack of P&I club coverage left local authorities shouldering firefighting and salvage expenses. In cold regions such as the Baltic, a leak from a neglected tanker would be disastrous since oil under ice is virtually unrecoverable.

7. Enforcement and Sanctions Mechanism

European countries are ramping up controls: Finland now insists on civil liability certificates from tankers coming into its exclusive economic zone, and Germany insists on oil spill insurance proof in the Fehmarn Belt. The EU’s 19th sanctions package calls for putting 118 ships on its blacklist and prohibiting Russian LNG imports by 2027. Its enforcement relies on port state control, registry checks, and coordination with G7 allies to shut reflagging loopholes.

8. Military Escalation Risks

Interdicting shadow fleet ships threatens confrontation. In May, Russian fighter jets buzzed an Estonian warship trying to halt a tanker. The Kremlin has sent warships to escort shadow fleet ships, making boarding tougher and escalating the risk for coastal states trying to enforce sanctions.

9. Global Market Implications

In spite of sanctions, Asian and Middle Eastern refinery demand props up the economic viability of the shadow fleet. Used tanker markets have bloomed, with prices for 15‑year‑old Aframax tankers having increased by over two times since 2022. The analysts point out that a majority of tankers constructed prior to 2010 now handle sanctioned oil, highlighting the entrenched position of the fleet in global energy flows.

The Boracay’s detention is a legal test case as well as a technological challenge. It embodies the convergence of marine engineering weaknesses, sanctions enforcement, and hybrid warfare a battlefield where tracking algorithms, naval interdiction techniques, and seabed protection systems are as important as diplomatic determination.