The United Nations’ reimposition of “snapback” sanctions on Iran represents a watershed moment in the protracted confrontation over Tehran’s nuclear policy, reinstating a package of economic and military sanctions that were suspended under the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). The sanctions, prompted by France, Germany, and the United Kingdom after months of dormant diplomacy, freeze Iranian assets outside Iran, stop arms deals, and reimpose limits on ballistic missile development an area notably left unregulated in the first agreement.

1. The Threshold of Nuclear: 60% Enrichment and Weapons-Grade Peril

Iran’s enrichment of uranium is already at 60% purity, a technical matter of a few steps from the 90% needed for weapons-grade material. Enrichment to the required level, by high-speed cascades of centrifuges, raises the content of fissile isotope U-235 exponentially. Whereas civilian reactors run on fuel enriched to 3–5%, from 60% to 90% is relatively much less of an advance in technical process than from natural uranium to 60%. Western intelligence estimates caution that Iran’s existing inventory already “sufficiently large to construct several atomic bombs” plus its ejection of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors, dramatically cuts down on any breakout effort’s early-warning time.

2. Snapback: A Veto-Proof Mechanism

The snapback mechanism, built into the JCPOA, was intended to be resistant to blockade by any one permanent member of the UN Security Council. This helped ensure that both Russia and China could not veto the reimposition of sanctions unilaterally. The E3 countries invoked Iran’s denial of IAEA access and inability to explain away high-enriched uranium as the tipping point violation. As U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio stated, the action was “an act of decisive global leadership,” although he stressed that “diplomacy is still an option.”

3. The Missile Gap in the 2015 Agreement

The JCPOA’s failure to include enforceable missile constraints created a strategic void. Iran has built up the Middle East’s largest ballistic missile force more than 3,000 missiles, according to U.S. estimates spanning short-range systems to medium-range missiles that can target Israel, the Arabian Peninsula, and southeastern Europe. Most of these systems are capable of being modified to deliver nuclear warheads. Solid-fuel designs, enabling quick launch readiness, and maneuverable reentry vehicles make it difficult to intercept by missile defenses. It is argued by analysts that any new agreement needs to incorporate Missile Technology Control Regime thresholds a 300 km range and 500 kg payload to separate defensive and offensive capability.

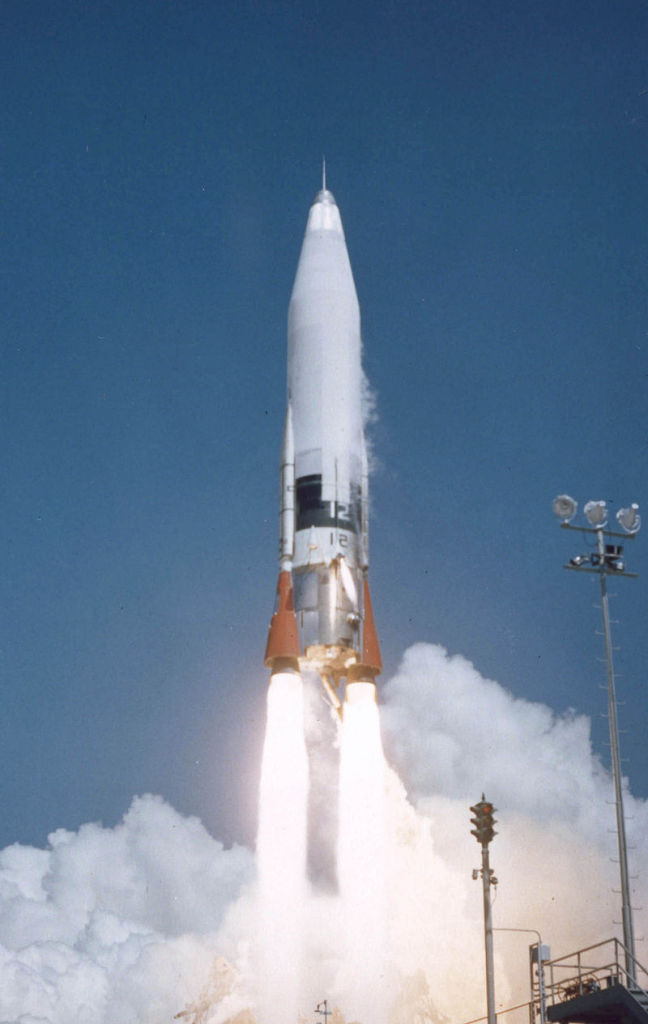

4. Space Launch or Strategic Signal?

Images obtained from September showed scorch marks at the Imam Khomeini Spaceport, which are compatible with a solid-fuel missile launch. An Iranian MP asserted, with no basis in fact, that the test launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), pushing beyond the Supreme Leader’s declared 2,000 km range limit and theoretically within range of all Europe. Though Tehran has historically utilized the facility for Zuljanah space-launch vehicles, the dual-use capability of such technology able to launch satellites into orbit or nuclear payloads is one that has been a concern about proliferation for many years. Fabian Hinz of the International Institute for Strategic Studies commented that the patterns of burning indicated a stage made of solid fuel, an essential element of any future ICBM capability.

5. Economic Burden Under Sanctions

The sanctions strike amid a severe domestic crisis. Iran’s rial has collapsed to record lows, driving annual inflation above 34% and pushing the cost of essential foods rice, meat, dairy up by 50–100% in a year. Pinto beans have tripled in price premium rice has doubled. This economic attrition, compounded by the aftermath of the June war with Israel, has deepened public discontent and fueled a surge in psychological distress, according to local health professionals.

6. The Oil and Energy Environment

Iran’s economic resilience is again challenged by the geopolitics of oil. International demand is still over 100 million barrels a day, with constrictive supply conditions exacerbated by OPEC+ cutbacks in production. Sanctions limit Iran’s capacity to openly sell crude, driving it toward cut-price, hidden sales to restricted purchasers. This undermines state revenues necessary to support both domestic subsidies and the expense of missile and nuclear programs.

7. Regional Security Implications

Iran’s missile forces are closely woven into its regional policy, providing proxies like Hezbollah, the Houthis, and Iraqi and Syrian militias with equipment. Transfers reach out from Tehran further while enabling live operational experimentation for new systems. The spread of precision-guidance technology, imperfect as it may be in proxy implementation, highlights the dual-track nature of Iranian weapons development domestic growth combined with export to allied nonstate actors.

8. Verification and Future Negotiations

Experts call for a renewed regime of verification based on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, including on-site inspections, remote monitoring, and pre-launch notifications. Imposing missile limits linked to sanctions relief would establish concrete incentives for compliance. A regional missile dialogue between Gulf countries and Israel could discuss deployment caps and stop transfers to non-state actors, recasting the issue as part of a regional security architecture rather than unilateral disarmament.

The re-imposed sanctions, together with Iran’s progressing enrichment and missile capabilities, put the region at a precarious crossroads of technology, strategy, and economic pressure. Without renewed inspections and verifiable controls on both fissile material and delivery systems, the technical hurdles to weaponization and warning time to detect it will continue to decline.