As Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen put it, the recent spate of drone incursions into her country’s airports represents “the most serious attack on Danish critical infrastructure to date.” The description was not hyperbolic. Within days, unknown unmanned aerial vehicles penetrated military and civilian airspace, causing flights at Aalborg, Billund, and Copenhagen airports to be suspended, and hovering above the Skrydstrup air base that serves as the home for Denmark’s F-16 and F-35 fighter jets. Officials have characterized it as a “hybrid attack” by a “professional actor,” the exposure of an Achilles’ heel that NATO’s eastern border has thus far failed to address.

1. The Anatomy of the Danish Incursions

Police sightings confirm the presence of drones in Esbjerg, Sonderborg, Aalborg, and Skrydstrup, with flight patterns suggesting deliberate targeting of strategic infrastructure. Defence Minister Troels Lund Poulsen referenced the fact that the drones were used “locally” rather than at distant range, rendering them more difficult to intercept. The decision against bringing them down was based on safety concerns debris, fuel, or batteries crashing could set fires among civilians. Though, as North Jutland chief police inspector Jesper Bojgaard Madsen admitted, “It was not possible to bring down the drones, which flew over a very extensive area during a couple of hours.”

2. Hybrid Warfare and Russia’s Record

While Denmark has shied away from directly accusing Moscow, the incidents are part of a broader pattern of Russian airspace breaches along the entire NATO eastern border. In Poland a month ago, 19 drones probed Warsaw’s airspace, and that prompted the first active confrontation between NATO and Russian forces since the invasion of Ukraine. Estonia saw three Russian warplanes loitering in its airspace for 12 minutes. These intrusions are seen by experts as deliberate probes on war preparedness and will without advancing to full-scale war.

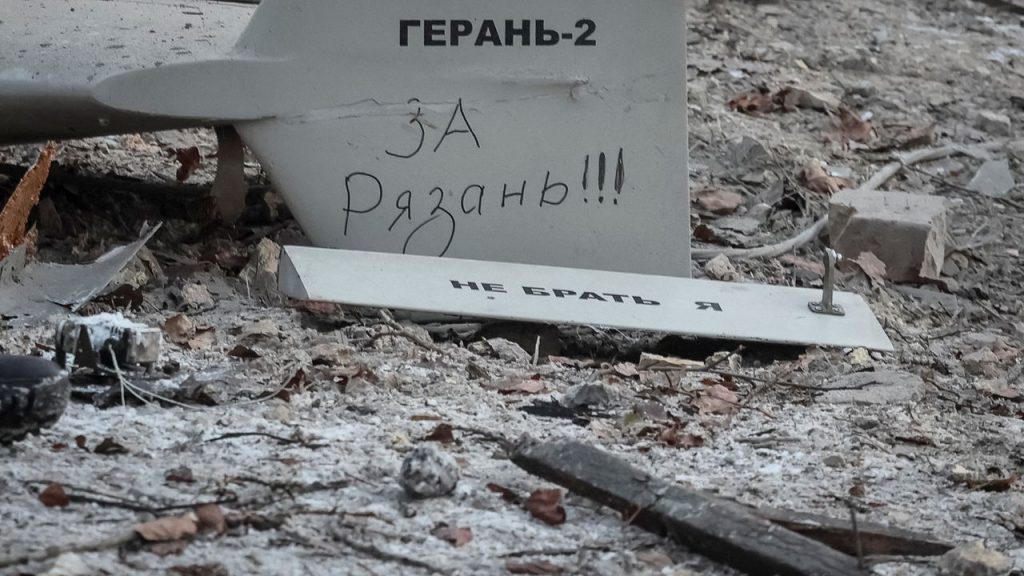

3. Technical Capabilities of Modern Drones

The UAVs employed in such attacks are unspecified, but European security officials have knowledge of the capabilities of today’s military UAVs. Systems like the Russian Geran-2 (which is based on Iran’s Shahed) can be armed with explosives, cruise at low altitude to evade radar, and travel up to 700 kilometers. The reconnaissance variants can loiter for extended periods, scanning defenses and gathering intelligence. Their low radar cross-section and low thermal signature make them difficult to detect with conventional air defense systems.

4. NATO’s Current Air Defense Posture

NATO’s Baltic Air Policing mission is designed to intercept manned aircraft, not clusters of toy drones. While integrated air defense systems can detect high-speed jets, they tend to struggle with low-flying UAVs. The alliance’s rules of engagement vary Poland’s been shoot-first, Denmark’s been more circumspect. As one NATO official warned, “If you find mush, you push. If you find steel, you withdraw,” demonstrating the deterrence dilemma.

5. Under Consideration: Counter-Drone Technologies

European planners are contemplating multi-layered counter-drone capabilities that combine radar, electro-optical sensors, RF jamming, and kinetic interceptors. Acoustic arrays, already deployed in Ukraine, can detect drones that the radar cannot. Lasers offer low-cost, directed take-downs without debris danger. But as University of South Denmark’s Kjeld Jensen noted, “From an engineering perspective it’s so much easier to build a drone that can fly than to build something that can keep them from flying.”

6. The “Drone Wall” Concept

The Drone Wall would be a cross-border network of sensors, electronic warfare gear, and command-and-control systems to detect, track, and knock out UAVs before they reach sensitive airspace. It would combine sensors, electronic warfare systems, and command-and-control systems across borders, as does the missile defense shield but tailored to drones. Defence Commissioner Andrius Kubilius anticipates crude detection to become operational in a year but full interception coverage will take longer to achieve.

7. Danish Long-Range Strike Plans

At the same time, Denmark is to acquire long-range precision missiles perhaps Tomahawk cruise missiles for Iver Huitfeldt-class frigates or JASSM-ER stand-off missiles for F-35s. Defence Minister Lund Poulsen stressed the need to destroy firing sites “far from Denmark,” borrowing a leaf from the conflict in Ukraine, which must strike drone and missile bases before they are in a position to fire.

8. Political and Strategic Implications

Invoking NATO’s Article 4 would bring allies together to discuss collective responses, as Poland and Estonia have already done this month. Yet there is still disagreement on the risks of escalation. Automatic shoot-down maneuvers will deter Moscow, some argue; others are concerned that they will precipitate direct war. The incidents have also underscored weaknesses in Europe’s ability to cooperate across borders on air defense, finance shared systems, and integrate disunited technologies.

9. The Wider Hybrid Threat

These incursions are only one element of a multi-domain campaign combining cyberattacks, sabotage of submarine cables, and even domination of industrial control systems. As MI5’s Ken McCallum warned, Russia’s GRU is “on a sustained mission to create chaos on British and European streets.” Drones are merely the most visible aspect of an all-encompassing drive to undermine resilience.

The Danish episodes have precipitated a reckoning: airports closed, military bases exposed to attack, and ministers racing to reassure. Wherever the source in Moscow, they have demonstrated that European airspace defenses remain far from fit for the age of drones. Next week’s NATO-EU meeting on the Drone Wall will test whether political urgency is turning into technical capability ahead of the next swarm.