It began with a warning that sounded more like a scene from a Cold War thriller than a modern-day policy address. Speaking at a Berlin space conference, German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius told delegates, “Thirty-nine Chinese and Russian reconnaissance satellites are flying over us… so be careful what you say.” The remark was not rhetorical. At the exact same time, two Russian Luch-Olymp reconnaissance satellites were tracking two Intelsat satellites employed by the German military, a strategy which has become synonymous with increasingly militarized space.

1. The Proximity Operations of the Luch-Olymp

The Luch-Olymp series, deployed in 2014 and 2023 respectively, has repeatedly been accused of “loitering” close to foreign satellites. The space vehicles fly in geostationary orbit, where satellites normally remain at a constant position relative to Earth. However, the Luch-Olymp satellites have shown the capability of making surprise close approaches, occasionally to within 10 kilometers of another satellite a very tight margin considering orbital velocities of about 3 kilometers per second. Such closeness allows for prospective interception of communication, high-resolution imaging, or dissemination of jamming signals.

2. Space Warfare Capability

Pistorius emphasized that both China and Russia are able to “jam, blind, manipulate, or kinetically disrupt satellites.” Jamming is the overwhelming of a satellite’s signal with noise to make communications useless. Blinding employs directed energy, e.g., lasers, to flood optical sensors. Manipulation can involve the transmission of false commands to change the function of a satellite. Kinetic disruption physical destruction can be done via direct-ascent anti-satellite missiles or co-orbital systems that can collide.

3. The Strategic Vulnerability of Satellite Networks

Satellite networks are, as Pistorius describes, “the Achilles’ heel of modern societies.” The Russian cyberattack on ViaSat in early 2022, for example, temporarily lost Germany control of 6,000 wind turbines, demonstrating how space-based infrastructure supports ground systems. From navigation and weather forecasting to military communications, breakdown in orbit can cascade into economic paralysis and compromised national defense.

4. Europe’s Dependence on External Launch Infrastructure

Europe’s reliance on U.S. facilities for launches into orbit is still a strategic weakness. The only spaceport on the continent to conduct heavy launches is in French Guiana, 500 kilometers north of the equator. Without it, Europe has to rely on NASA’s Cape Canaveral. This dependence restricts operational independence in launching or resupplying satellites in times of crisis, an opportunity an adversary might use.

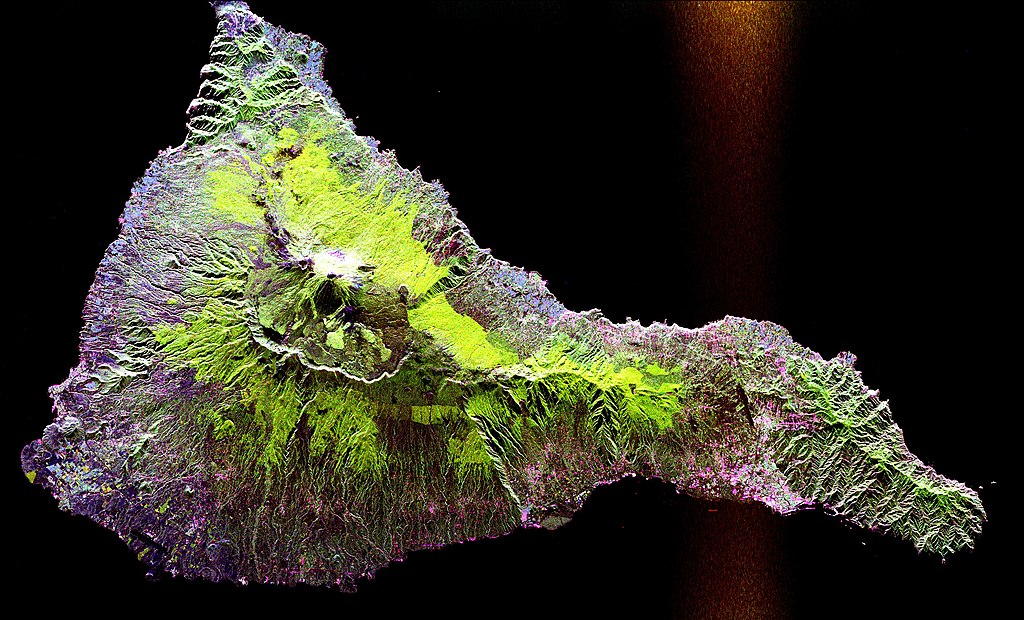

5. Real-Time Surveillance and Data Transmission

The 39 reconnaissance satellites Pistorius mentioned are not mere spectators. Fitted with high-resolution optical, synthetic aperture radar, and secure downlinks, they have the capability to relay information in real time to ground stations. These capabilities have the potential for near-instantaneous updating of intelligence so that opponents can follow troop movements, monitor facilities, and evaluate the military capabilities in readiness.

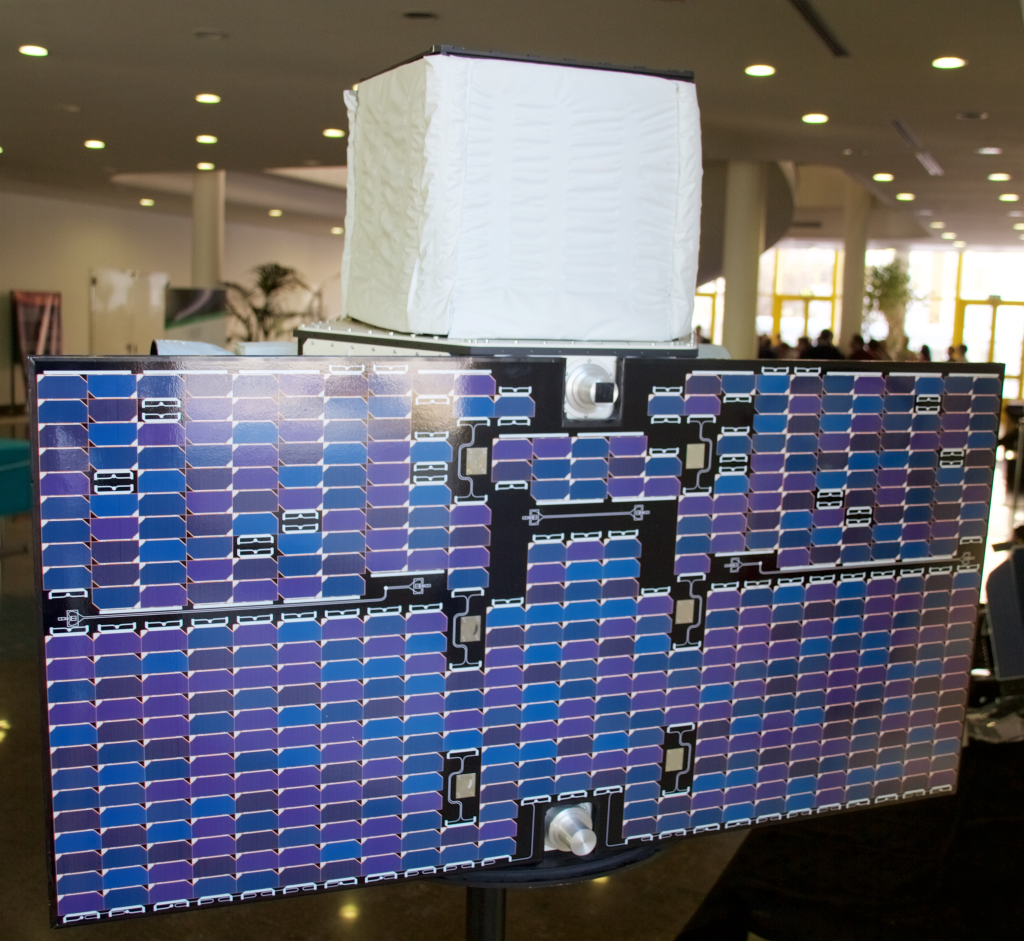

6. Financing Germany’s Space Defense Architecture

Berlin’s €35 billion five-year investment will pay for a jam-resistant constellation of military satellites that can resist jamming and kinetic attacks. Proposals involve increased orbital observation with radar and telescopes, “guardian satellites” to watch over and defend critical assets, and a hardened military satellite command center in the Bundeswehr Space Command, founded in 2021. These steps are designed to discourage aggressive maneuvers and protect Germany’s strategic communications.

7. Offensive Capabilities as Deterrence

Pistorius emphasized the importance of speaking about offensive capabilities in space. Though specifics are classified, such capabilities might include counter-jamming technology, powerful lasers for blinding enemy sensors, or co-orbital platforms for intercepting and disabling hostile satellites. The rationale is the same as on the ground: deterrence becomes most believable when it has the potential to retaliate in similar fashion.

8. The Broader Geopolitical Context

Shadowing German satellites against the backdrop of growing tensions between Russia and NATO, such as recent airspace incursions over Estonia and suspected Russian actions in disrupting drones at Danish airports. Space, previously regarded as a neutral domain, is now a battleground where the geopolitical competition reaches beyond the atmosphere of Earth. The interconnection between orbits and battles on the ground highlights the interconnected nature of contemporary warfare.

9. The Technological Advantage of Adversaries

China’s “highly agile and dynamic maneuvers” in space and Russia’s accurate placement of spy satellites demonstrate decades of investment in space control technology. Autonomous navigation systems, sophisticated propulsion for precise orbital maneuvers, and secure, encrypted communications immune to intercept are among them. These allow extended surveillance and quick adaptation to changing operational requirements.

Germany’s public recognition of these threats represents a sea change in European space policy. The investment in orbital robustness, combined with efforts to achieve independent launch capability, represents an effort to close the capability gap with world space powers. Whether or not this will suffice to dissuade the close-tracking methods of the Luch-Olymp satellites is uncertain.