Carry a .25 if it feels good to you, but never load it. Late Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper’s tongue-in-cheek counsel still resonates in discussions on defensive caliber. At the high-stakes game of self-protection, choosing the wrong caliber can be the difference between halting an attack and exposing yourself to deadly danger.

Although any gun is better than no gun at all, not every handgun cartridge provides the combination of penetration, dependability, and manageability required in life-or-death situations. Decades of ballistic gelatin testing, police exposure, and civilian defensive utilization have isolated various calibers that repeatedly fall short under stress. Some do not have sufficient energy to travel to vital organs, others have marginal reliability, and some produce punishing recoil that retards subsequent shots.

This article looks at seven calibers that experienced trainers and ballistics professionals recommend avoiding in everyday carry. Each item discusses why the round comes up short, the statistics behind its shortcomings, and where if at all it still has a place.

1. .22 Long Rifle – Low Recoil, Lower Reliability

The .22 LR’s ubiquity stems from its affordability, minimal recoil, and quiet report. Yet its rimfire design inherently suffers from higher misfire rates often 1–2% in premium loads and up to 8–10% in bulk ammunition. With muzzle energy frequently under 200 ft‑lbs, it struggles to meet the FBI’s 12–18 inch penetration benchmark, especially through heavy clothing.

Contemporary defensive cartridges such as Federal Punch and Winchester Silvertip enhance performance, with the Punch measuring 13.75 inches in gel from a snub‑nose revolver. Nevertheless, as USCCA testing points out, .22 LR “may not get the job done” against a committed assailant. It is still a great training and pest‑control cartridge, but as a first‑line carry option, its reliability and terminal effect limitations are difficult to overlook.

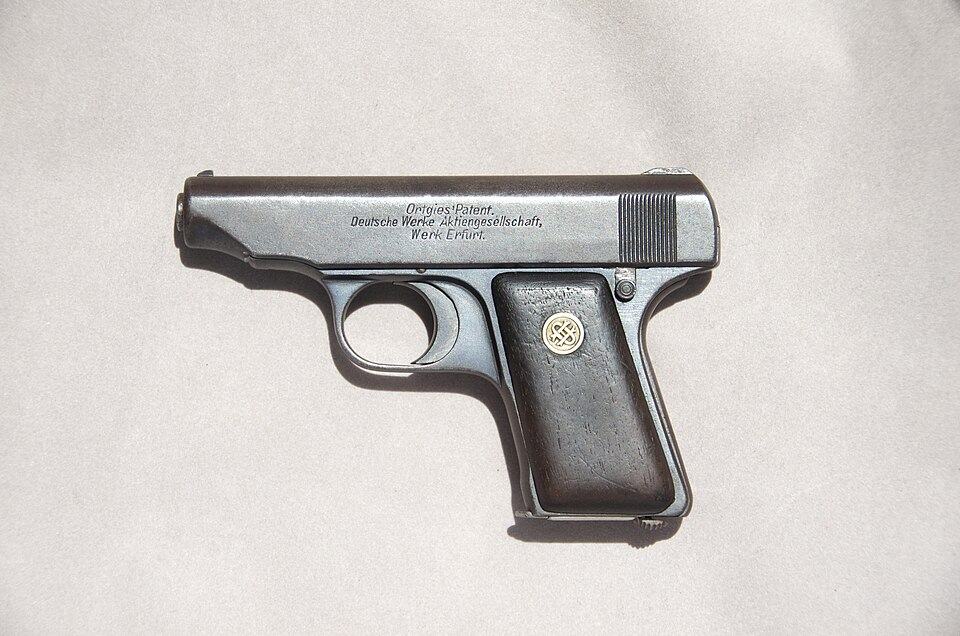

2. .25 ACP – An Anachronism Supplanted by Contemporary Pocket Pistols

Conceived in 1905 to replicate .22 LR ballistics in a centerfire configuration, the .25 ACP previously ruled vest-pocket pistols. Now, it generates less than 70 ft‑lbs of energy half that of most .22 LR loads and exhibits minimal expansion in gel testing. In ballistic testing, high-end hollow points such as Speer Gold Dot penetrated just roughly 10 inches, far from FBI specifications.

Its centerfire reliability is argued by proponents, as well as its minute platforms, yet the majority of .25 ACP pistols have crude sights, clunky controls, and short longevity. Greg Ellifritz’s stoppower study discovered 35% of victims shot with .25 ACP were not incapacitated approximately twice the failure rate for .380 ACP and more. When there are micro‑.380s and 9mms available in the present day, the .25’s compromises are seldom justified.

3. .32 ACP – Soft Shooting, Soft Impact

John Browning’s 1899 .32 ACP equipped police and military for decades, but its mean muzzle energy of 125–170 ft‑lbs brings it closer to .22 LR than to contemporary service cartridges. Expansion under heavy clothing is uneven, and many bullets do not penetrate to 12 inches.

Whereas its light recoil facilitates control, cartridge availability is sparse, and the majority of platforms are antiquated designs such as the Walther PPK. For those who can accommodate a .380 ACP, the ballistic benefits are dramatic. The role of the .32 ACP now belongs to recoil-sensitive shooters willing to sacrifice stopping power for concealability.

4. .410 Shotshell in Revolvers – Spread Without Stopping Power

Revolvers such as the Taurus Judge offer shotgun‑style versatility at the expense of firing .410 or .45 Colt. In the real world, short barrels cut velocity, and birdshot patterns may open to 30 inches at 15 feet, with central holes big enough to miss small targets completely. In Tom Givens’ tests, #9 shot did not penetrate a plastic bottle, and even #4 shot was unable to penetrate ¾‑inch plywood.

Buckshot loads work better up close, with Federal’s four‑pellet 000 Buck making compact patterns within seven yards. Past seven yards, the spread threatens to strike innocents, and .45 Colt precision from the Judge’s extended cylinder gap is subpar. For defensive purposes, traditional handgun calibers are more reliable.

5. Underperforming .380 ACP Loads – A Caliber on the Edge

The .380 ACP can be effective, but many popular loads fail to meet the FBI’s 12‑inch penetration minimum from short barrels. In gel testing, some hollow points expanded rapidly but stopped short, while others penetrated adequately but barely expanded.

Premium choices such as Federal HST, Hydra-Shok, and Speer Gold Dot increase the chances, depositing 189–223 ft-lbs of power with measured expansion. The small, light revolvers or semiautos usually chambered in .380, though, generate snappy recoil that degrades accuracy. Those carriers devoted to this cartridge need to be choosy about ammunition and practice diligently to compensate for its marginal ballistics.

6. 10mm Auto – Power With a Price

Initially chosen by the FBI for its energy and velocity levels usually in excess of 600 ft‑lbs the 10mm Auto performs well in penetration and stopping capabilities. However, its recoil, muzzle blast, and potential for over-penetration render it difficult for most shooters to use effectively in urban defensive situations.

In Lucky Gunner gel tests, best 10mm loads equaled .40 S&W performance when bullet design was optimized, questioning if the additional recoil is worth the cost for human threats. Where it really excels is in wilderness defense of large animals, where deep penetration is critical. For most concealed carriers, 9mm or .45 ACP provides a balance of control and terminal effect.

7. .38 Special from Ultra‑Short Barrels – Tradition Meets Physics

The defensive heritage of the .38 Special cannot be denied, but snub‑nose revolvers with barrels under two inches shoot velocity away, taking hollow point expansion with it. In two‑barrel‑length gel tests, most loads struggled to hit the 12‑inch penetration baseline, and fabric clogs frequently brought expansion to a complete stop.

+P loads contribute recoil without the corresponding ballistic improvement in these ultra‑short platforms. Prudent ammunition choice preferring loads designed for short barrels can reduce the issue, but the shooter will have to accept the compromise between controllability and terminal performance.

Selecting a defensive caliber is a matter of achieving a balance between power, controlability, and reliability. The cartridges discussed here are not powerless, but each requires sacrifices that most shooters can ill afford under duress. Contemporary service calibers such as 9mm, .40 S&W, and .45 ACP coupled with well-established defensive loads represent a more consistent compromise. The aim in self‑defense is not raw power at all costs, but delivery of accurate, effective fire when it really counts.