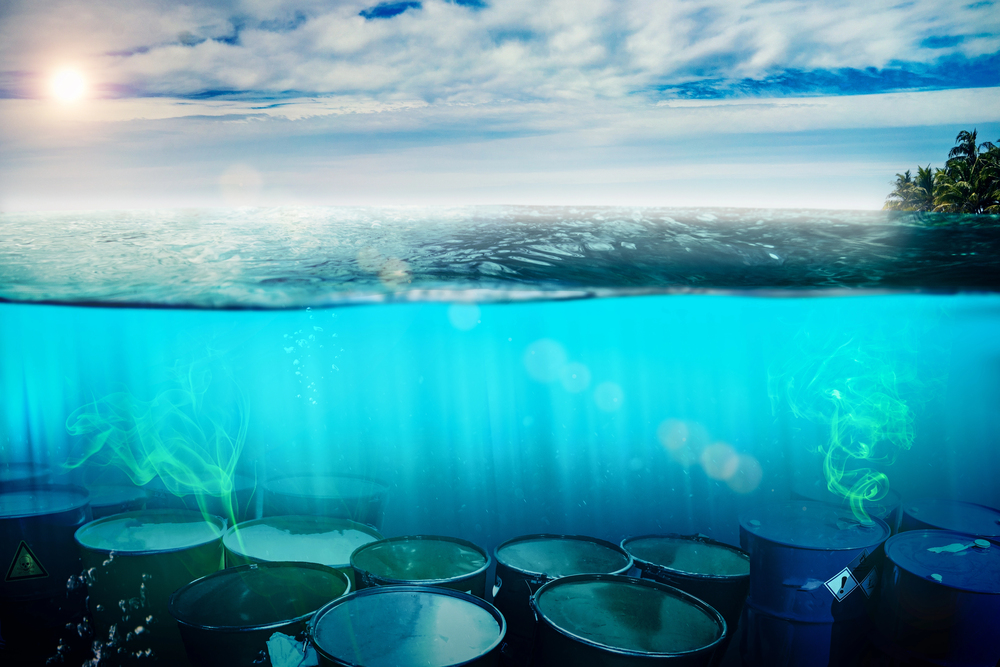

“The more we look, the more we find, and every new piece of information is spookier than the last,” cautioned Mark Gold of the Natural Resources Defense Council. For decades, the bottom waters off Southern California had a toxic secret thousands of industrial trash barrels strewn across the ocean floor, with little noticed or investigated. Now, a convergence of new technology, archival research, and marine science is uncovering their secrets.

What started as a ghostly white halo mystery around some barrels has come to be an intricate tale of chemical resilience, industrial past, and environmental disturbance. The revelations upset decades-long beliefs regarding what was disposed, how it acts under water, and the threats it presents to marine life and human health. Below are seven of the most remarkable findings from this ongoing research.

1. From DDT Rumors to Alkaline Waste Reality

When remotely operated vehicles originally captured images of barrels ringed by pale halos in 2020, people believed they contained DDT, the infamous pesticide that was outlawed during the 1970s. However, sediment analyses in the vicinity of five barrels showed no increase in DDT levels. Instead, UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography researchers discovered that the barrels that produced halos were caustic alkaline waste with pH contents close to 12 as alkaline as household bleach. Lead author Johanna Gutleben added, “No one was considering alkaline waste beforehand and we might have to begin searching for other stuff too.” The origin of the waste is unknown, but both the manufacture of DDT in the area and local oil refining produced alkaline byproducts.

2. The Creation of the Spooky White Halos

The halos are not just visual wonders. When alkaline waste seeps, it reacts with magnesium in the seawater to become brucite, a concrete-like mineral that binds the sediment together. Brucite dissolves over time, maintaining high alkalinity and causing calcium carbonate precipitation, which settles as white dust covering the barrels. It not only changes the chemistry of sediments but also forms a physical crust so tough that scientists had to employ robotic arms in order to gain samples. The halos can now be used as a possible visual indicator for contaminated barrels on the entire seafloor.

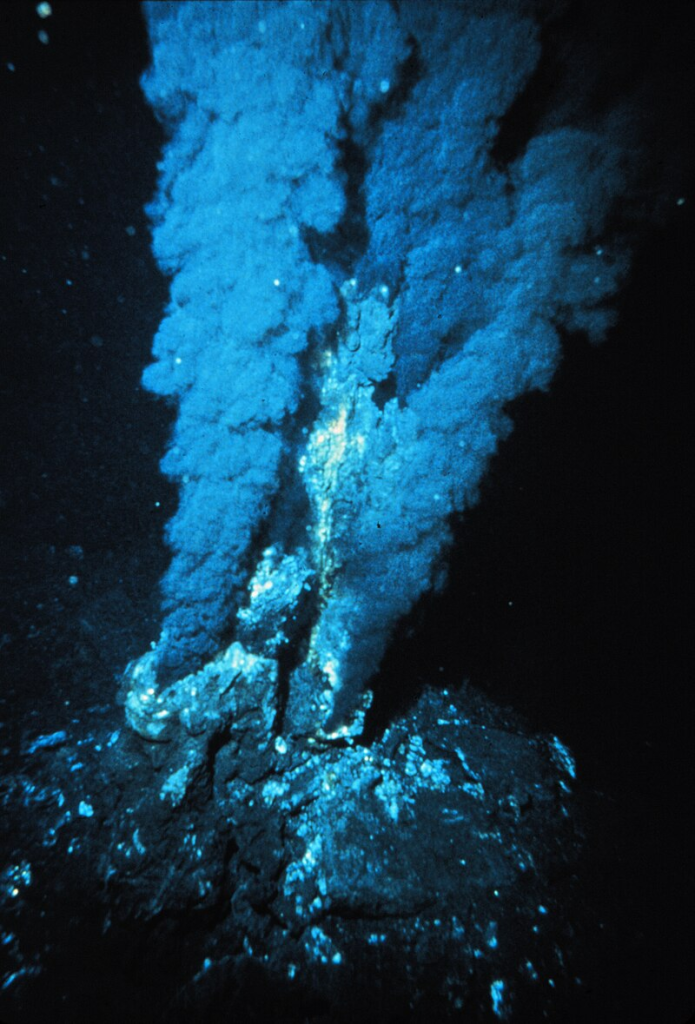

3. Extreme Environments in an Unexpected Place

The alkaline plumes have transformed patches of the seafloor into habitats akin to deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Microbial DNA analysis revealed extremely low diversity, with only a few extremophiles microbes adapted to survive in harsh alkaline conditions present. Paul Jensen, senior author of the study, remarked, “It’s shocking that 50-plus years later you’re still seeing these effects.” Such zones are inhospitable to most marine life, disrupting benthic ecosystems and reducing biodiversity among small animals.

4. A Wider Dumping Legacy

Between the 1930s and early 1970s, 14 deepwater dumping sites off Southern California were utilized to dump refinery residue, chemical byproducts, military ordnance, and radioactive waste. In 2021 and 2023, surveys accounted for more than 27,000 probable barrels and over 100,000 debris items. Prior records show that materials were frequently dumped from ships in motion, resulting in linear trails of miles-long barrels. This industrial dumping was permissible when it took place, but the long-term effects of it are only now visible.

5. Radioactive Waste Among the Barrels

Archival research by UC Santa Barbara’s David Valentine revealed that California Salvage, the same firm hired to rid the country of DDT waste, also processed low-level radioactive waste, including tritium and carbon-14. Some isotopes might have declined, but more dangerous materials could be present. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Ken Buesseler warned, “Once it’s there, you can’t go back and get it.” That adds urgency to the need to know precisely what is stored inside the corroding containers.

6. Persistent Pollutants That Defy Time

Both alkaline waste and DDT are now considered persistent pollutants, able to persist for decades or millennia. Unlike the anticipated expectation that alkaline waste would rapidly dilute in seawater, it has persisted for more than a half century. Their persistence guarantees that their ecological effects changed sediment chemistry, impacted microbial communities, and likely bioaccumulation will persist deep into the future, making remediation attempts challenging.

7. The Remediation Challenge

Removing the contaminated sediments or barrels physically is full of logistical and environmental hazards. Jensen described the greatest DDT concentrations as being only a few centimeters beneath the surface; to disturb them would be to unleash clouds of toxins into the water column. Containment or restricting human use in areas contaminated are among options under consideration. At the same time, scientists are investigating microbial degradation as a potential long-term solution, testing out bacteria that could disassemble DDT without harming anything else.

The discoveries from the seafloor of Southern California are a grim reminder of the way industrial processes nearly five decades ago still influence marine environments today. With each new find from alkaline waste halos to the shadow of radioactive dumping each increases the sense of urgency in the demand for full investigation and policy response. While scientists chart the scope of this underwater toxic record, the challenge will be not just to learn its full extent but how, or whether, it can ever be reversed.