“How do you win a race when you keep changing the track?” That was the not-so-secret mantra ringing out at the Senate Commerce Committee hearing on September 3, as lawmakers and former NASA officials grappled with an uncomfortable fact: the United States is announcing a new space race with China, but with no clear, technically informed strategy to win it.

1. Political Rhetoric vs. Programmatic Reality

Sen. Ted Cruz described space “a strategic frontier with direct consequences for national security, economic growth and technological leadership.” But witnesses like former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine cautioned that political rhetoric hasn’t been accompanied by stable architectures or consistent funding. The Artemis program the United States’ premier lunar initiative has been constantly redesigned, with budgets slashed, timelines extended, and priorities altered from administration to administration. Bridenstine cautioned, “Unless something changes, it is highly unlikely the United States will beat China’s projected timeline to the Moon’s surface.”

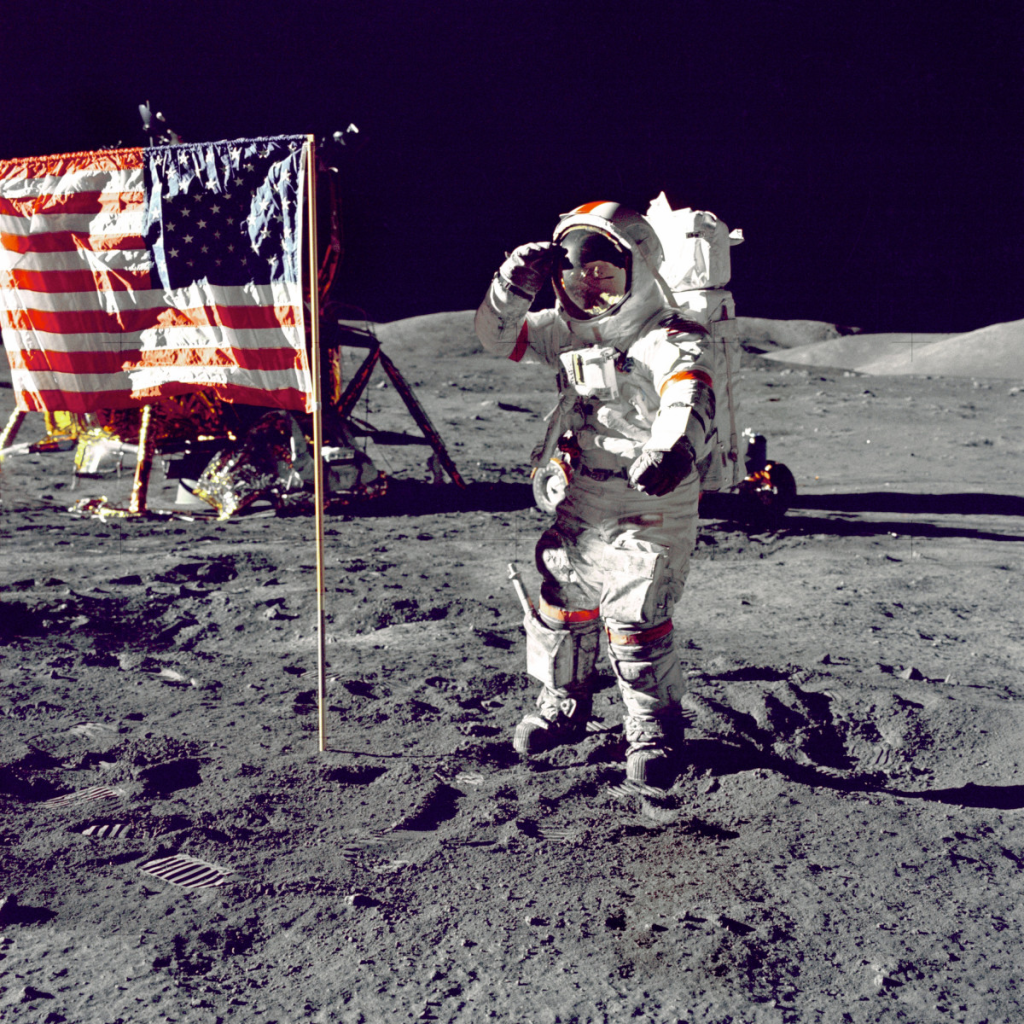

2. The Fragile Artemis Architecture

At the heart of Artemis is the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion capsule the only human-rated super heavy-lift system currently operational. Hardware for missions through Artemis 9 is already in production. But to reach the Moon, NASA is pinning its hopes on SpaceX’s Starship Human Landing System, a spacecraft that has to learn to refuel in orbit using as many as dozens of tanker missions before a single crewed lunar touchdown. Starship’s recent high-profile test failures and the mission profile complexity have also magnified fears that America may miss its 2027 Artemis 3 deadline.

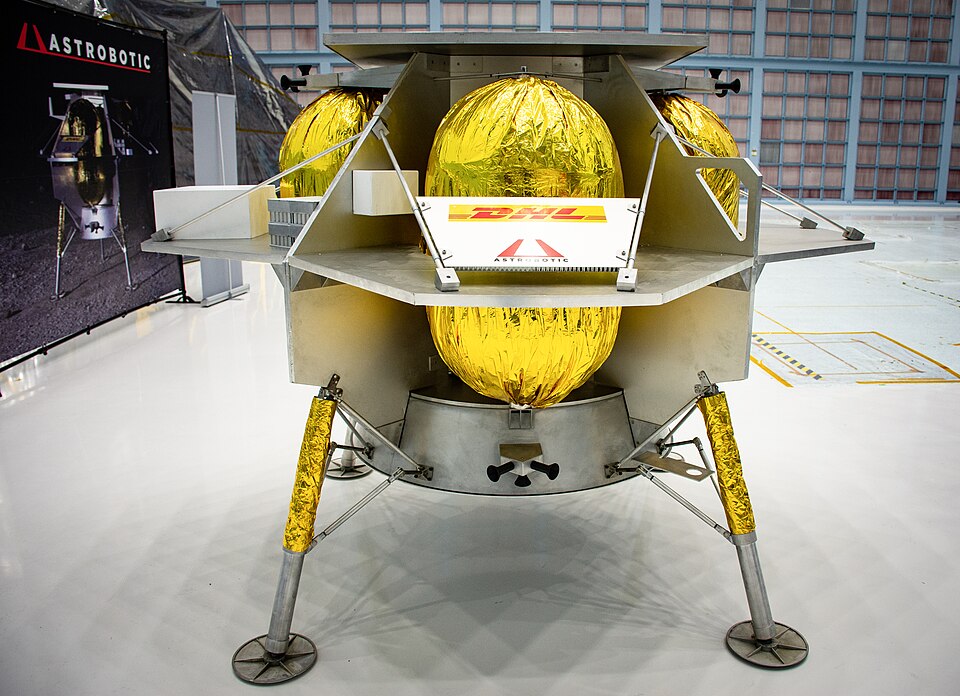

3. Commercial Alternatives and Political Resistance

The White House had suggested phasing out SLS and Orion after Artemis 3 to lower-cost commercial launchers, and the cancellation of the Gateway lunar space station to target resources to the surface. Congress both opposed these actions, increasing $6.7 billion to sustain SLS, Orion, and Gateway. Critics see this as cementing legacy systems over agility, while proponents feel that “any sweeping changes in NASA’s architecture at this juncture jeopardize United States leadership in space.”

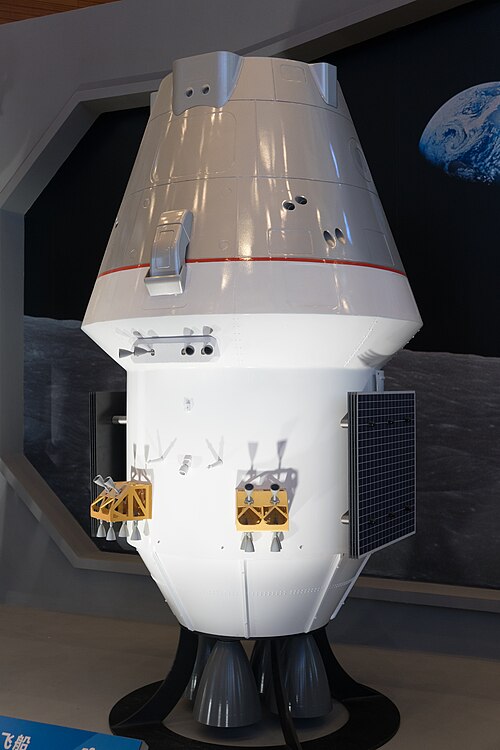

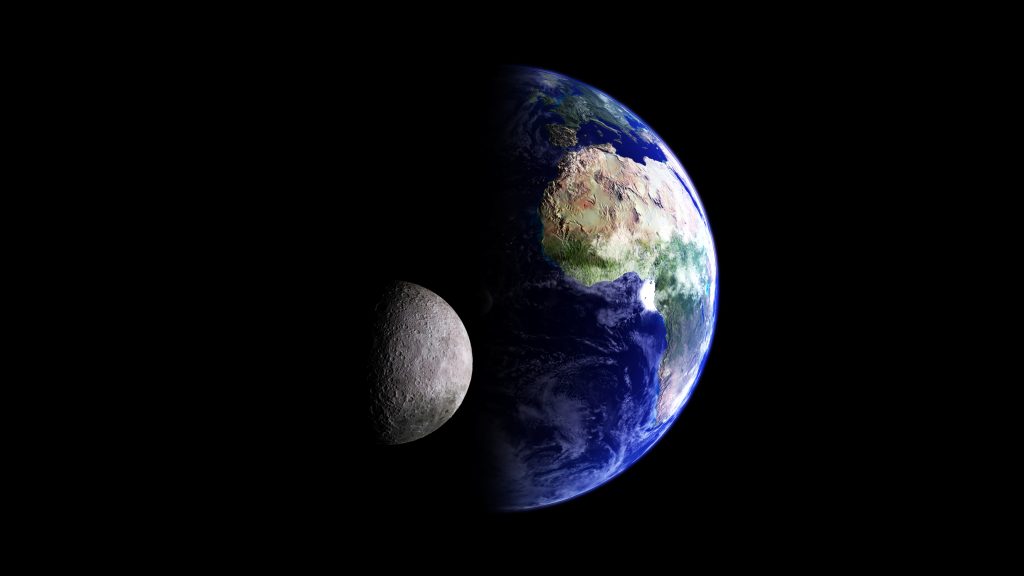

4. Gateway’s Geopolitical Significance

Gateway a lunar-orbiting modular station is budgeted at $750 million per year through 2028, with more than 60% of its cost covered by international partners. Redwire’s Mike Gold cautioned that scrapping Gateway would “waste this unprecedented worldwide investment” and drive allies into China’s developing lunar alliances. As a permanent cislunar base, Gateway might also be a logistical stop and a diplomatic anchor in the Earth-Moon system.

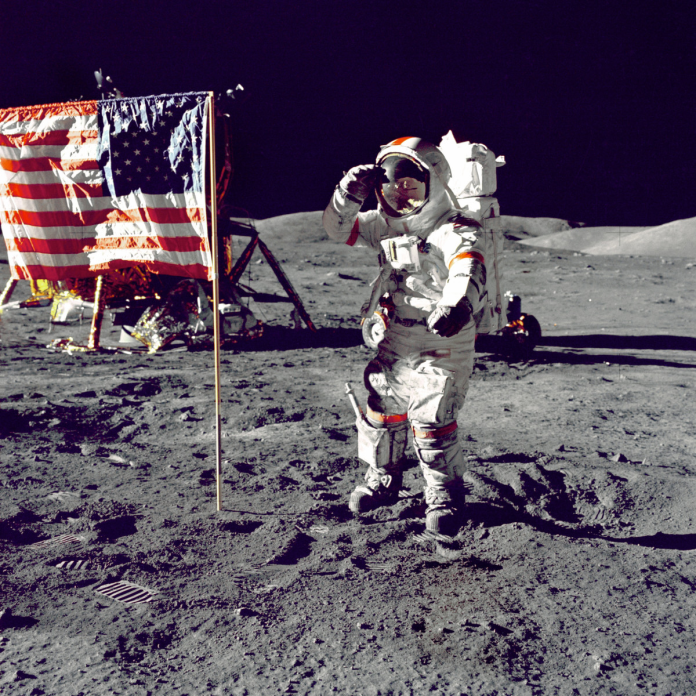

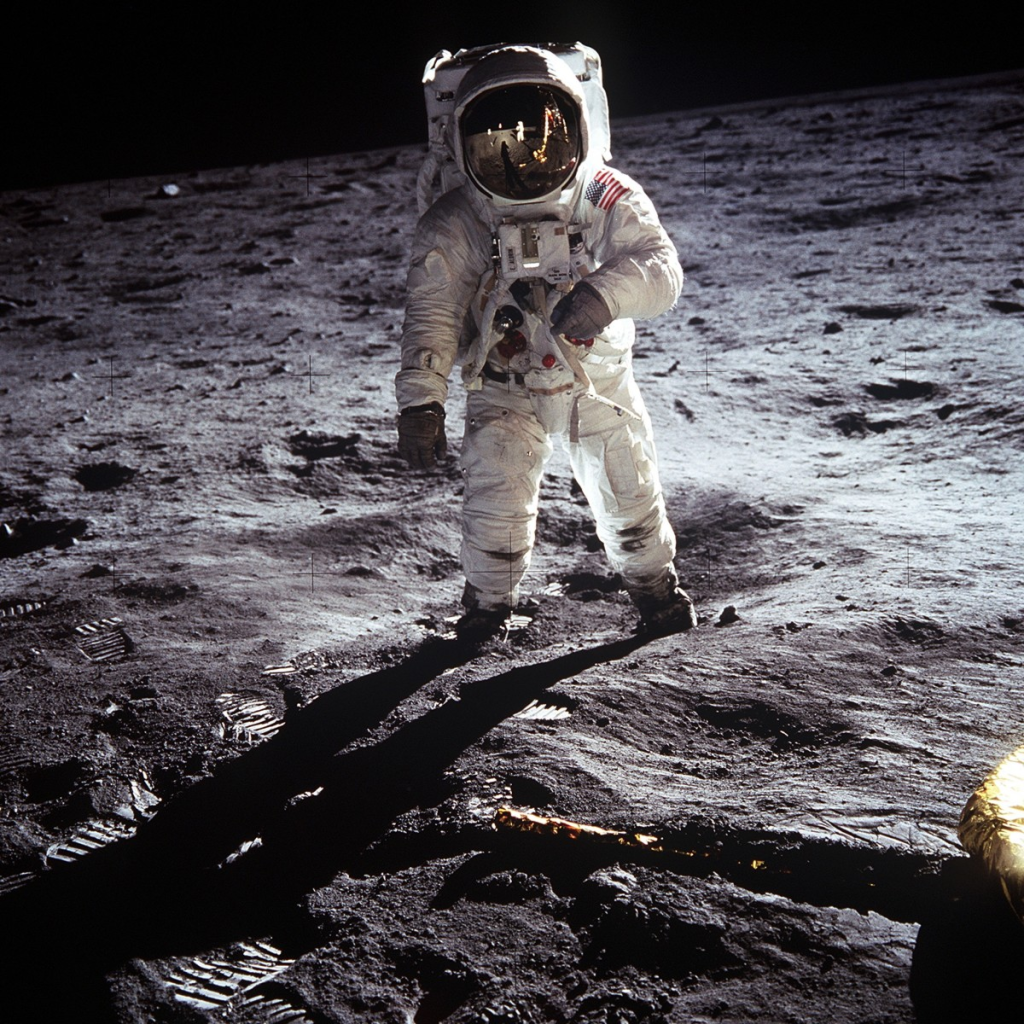

5. China’s Steady March

China is systematically developing its lunar equipment: the Mengzhou crew capsule, Long March 10 rocket, Lanyue lander, and Wangyu spacesuit are all undergoing prototype testing. A human lunar landing is officially planned for 2030, though U.S. officials suspect that Beijing might be able to move faster. “The nations that arrive first will write the rules of the road about what we can do on the moon,” Gold stated. China’s top-down approach stands in striking contrast to NASA’s politically balkanized strategy.

6. The 100 kW Lunar Nuclear Reactor Gambit

To overshoot the competition, the administration has directed a 100-kilowatt nuclear fission reactor on the Moon in 2030, more powerful than previously 40 kW ideas. The device will have to be contained within a 15-metric-ton lander, run independently for ten years, and utilize a closed Brayton cycle for power conversion. This sort of output could support ecosystems, life support, and whole fleets of robotic ISRU extractors mining oxygen and hydrogen from lunar water ice. But Katy Huff and others caution that “the 2030 target does not align well with recent budgetary trends” and will demand precision engineering, meticulous safety planning, and continuous funding.

7. Engineering and Safety Challenges of Lunar Fission

Lunar reactors have to handle heat in temperature fluctuations of up to 200°C, function under low gravity, and be sealed away from the regolith environment. Launch safety requirements require that the reactor be shipped unfueled or loaded with new uranium to reduce radiological hazard. After deployment, shielding, self-shutdown systems, and long-term waste storage on the lunar surface, presumably become necessary. Inability to resolve these might endanger crew safety as well as global faith in U.S. space nuclear capabilities.

8. Economic and Industrial Stakes

Artemis supports 2,700 suppliers across the U.S., from small machine shops to aerospace giants. NASA estimates every $1 invested returns $3 to the economy. Yet uncertainty over mission cadence “maybe once a year if lucky post-Artemis 4,” as one industry observer put it is already rattling suppliers. Allen Cutler warned, “We need people working on Artemis not working on their resumes.”

9. The Missing Grand Strategy

Lt. Gen. John Shaw called for the implementation of an integrated national space strategy that incorporates civil, commercial, and defense objectives. Such a system would provide milestones for nuclear energy, cislunar communication, and planetary defense without succumbing to the “cast to and fro from one administration to the next” Bridenstine deplored. Without it, the U.S. can expect piecemeal endeavors as China implements an integrated Earth-Moon program.

The hearing ended on Cruz’s somber warning: “If our competitors develop masterful space capabilities, it would be a calamitous danger for America.” But without a technically viable, politically sound, and fully funded strategy, the U.S. could end up merely observing from lunar orbit or from back on Earth as China claims the Moon’s south pole for itself.