Eight decades since the guns fell silent in the Pacific, the ocean floor is still carrying the equipment of war and with it, a seeping environmental problem. Thousands of ships, planes, and undetonated bombs lie or are buried beneath the blue-green waters, their metal hulls and ordnance rusting, leaking poisonous legacies into delicate ecosystems. Scientists and engineers are warning that global warming is speeding up the rot, turning the artefacts into sources of explosive pollution and hazard.

1. A Seabed Arsenal of Corrosion

The Pacific War in World War II left not a few wrecks scattered on the sea bottom but an estimated 3,800 wrecks of the same type. They were primarily oil-burning steel ships with hulls measuring an average of 25 millimetres thick. At 0.1 to 0.2 millimetres annually, decades of seawater exposure have eroded these structures by more than 30 per cent. This erosion makes once-sealed fuel tanks and ammo bunkers leaky and propels hydrocarbons, heavy metals, and explosives into surrounding waters. At Solomon Islands’ Iron Bottom Sound, where 111 ships and 1,450 aircraft rest, earthquakes have already induced suspected oil seepage, such as in the 2022 7.0 earthquake.

2. Chemical and Radiological Time Capsules

Other than oil, there are other shipwrecks with ordnance containing TNT, depth charges, and even chemical weapons such as mustard gas. Japanese depth charges in the Helmet Wreck located off the coast of Palau are corroding and emitting acid into the harbour. In the Marshall Islands, an opportunity for radioactivity exists: the Runit Dome, a 350-foot-wide concrete dome over over 100,000 cubic yards of nuclear-contaminated earth, was built in the late 1970s with no concern for sea-level rise. Seawater laps its shores today, and intense storms can double levels of radioactive sediment in nearby seas to 84 times the background.

3. Ecological Impacts from Microbes to Megafauna

North Sea experiments show low-level pollution from WWII vessels is enough to reorganize microbial populations. Hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria like Rhodobacteraceae thrive in fuel leaks, changing the basis of the marine food web. In tropical seas, danger is more pronounced: mangroves and coral reefs that stabilise shores and add diversity are especially vulnerable to poison incursion. Studies off Puerto Rico found sea life near unexploded bombs with chemical traces, evidence that the toxins had entered the food supply.

4. Human Health Threats Emerge

Papua New Guinea, the Solomons, and Palau’s societies always find unexploded bombs when they plow the fields, fish, or merely construct schools over 200 bombs were discovered buried under one schoolyard in one case. The explosive materials hold heavy metals like cadmium and lead, which disrupt endocrine systems and elsewhere have been linked with cancers and birth defects. More recent British Army ammunition technicians’ survey revealed much higher bladder cancer rates, indicating exposure to explosive compounds’ prolonged occupational hazards.

5. Climate Change as a Force Multiplier

Sea level rise, strengthening cyclones, and changed currents resuspend buried or submerged past threats. 2015 Cyclone Pam broke thousands of ordnance to the surface in Tuvalu and Kiribati. A bomb was found off the coast of Lord Howe Island in 2020, believed to have been washed into place by storm surges. Ordnance can be moved hundreds of kilometers from its original known location by landslips and floodwaters, making it difficult to find and remove. Partial submergence at the turn of the century is anticipated for the Runit Dome with unforeseen consequences of radioactive contamination.

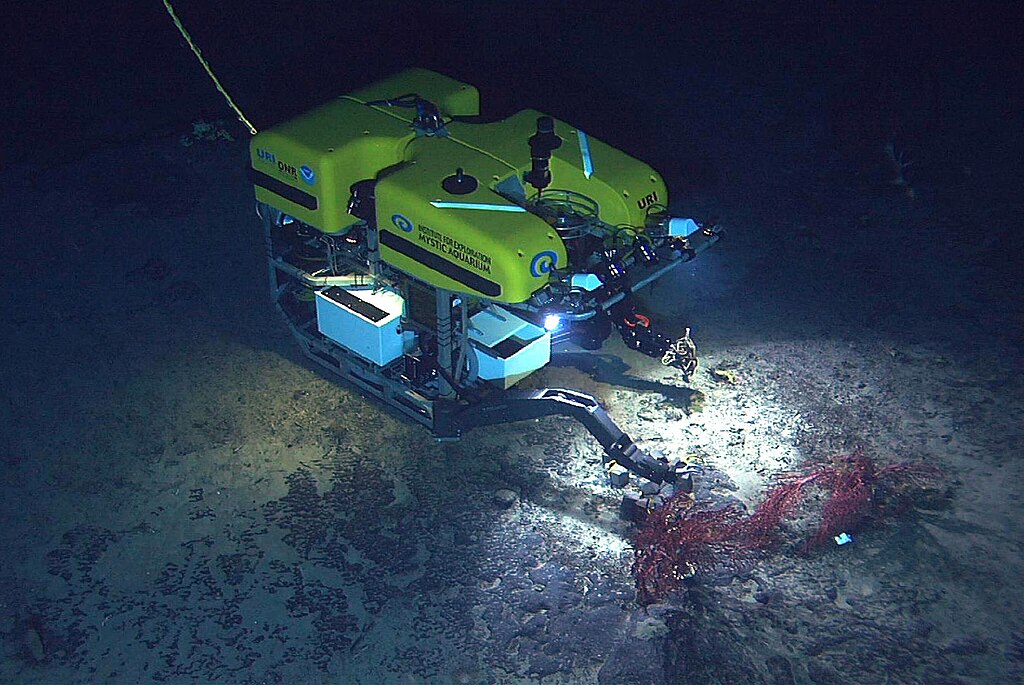

6. Engineering Challenges in Detection and Removal

Detection and neutralization of sea hazards include advanced sonar charting, magnetometry, and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). These technologies are employed by the Australian Defence Force Operation Render Safe to identify and dispose of unexploded ordnance. But each wreck is a unique situation, varying with depth, combat damage, and weather exposure, so risk assessment must be site-specific. As NOAA’s Doug Helton explains, “With most pollution response, you don’t have the luxury of choosing when to do it you try to determine what’s the optimal time of year, with the best salvage conditions.”

7. The Cost and Complexity of Remediation

Salvages are expensive and logistically demanding. It took a record nearly three years and $6 million to buoy the USS Mississinewa oil at Micronesia; it was $19 million to drain oil from the S.S. Jacob Luckenbach off San Francisco. Wrecks in most cases turn into war graves, which involve sensitive balancing acts between heritage and conservation. Some, like the USS Arizona, continue leaking oil at amounts that will persist centuries.

8. Regional and Diplomatic Dimensions

Pacific island nations have long demanded greater openness by wartime superpowers. Solomon Islands officials urge Japan and America to release wartime cargo manifest records to more precisely ascertain risks. Diplomatic initiatives remain skewed, as some oil slick incidents are followed by a refusal to take action. Cartographic activities such as Canadian cartographer Paul Heersink’s database of 15,000 WWII wrecks are meanwhile helping to set priorities for intervention, with 53 priority wrecks already discovered in the Western Pacific alone.

9. Monitoring and Data Gaps

Both chemical and radiological risks must be monitored continuously, experts point out. At Runit Dome, ocean radioactivity specialist Ken Buesseler describes how today a secondary radiation source relative to surrounding sediments, “a lot is dependent on future sea-level rise and how storms and seasonal high tides impact the flow of water in and out of the dome.” Information must become available directly to affected communities to establish confidence and inform local safety precautions. The Pacific war trash is not a fossil record anymore; it’s an environmental engineering challenge of the day. It will require concerted funding, technology creativity, and integration of indigenous and scientific knowledge before rusting, currents, and climate turn these remnants into total tragedies.