Can a plane really just disappear from the world’s best detection systems? The F-22 Raptor gets closer than any production fighter, and its engineering explains why. Its low observability isn’t the product of one breakthrough but rather a carefully layered design that brings together aerodynamics, materials science, propulsion engineering, and electronic warfare in one, coherent system.

1. Aerodynamic Shaping and Planform Alignment

The Raptor’s exterior mold line is an exercise in radar deflection. Edge lines and angular surfaces are designed so that radar waves are deflected away from the source instead of reflected back toward it. This “planform alignment” runs across wings, tail fins, and fuselage, reducing the number of aspect angles that create a strong radar return. As opposed to the faceted F-117, the F-22 incorporates smooth curves that preserve stealth without compromising aerodynamic performance essential for its Mach 2 maximum speed and highly dynamic maneuverability.

2. Radar-Absorbent Materials and Surface Treatments

Under its silver-gray skin is a matrix of radar-absorbent composites and radar-defeating structures. These materials absorb radar energy and dissipate it harmlessly as heat. As Langley AFB maintainers explain, “If you’ve got a lot of damages, the aircraft is more easy to detect, so we attempt to minimize those damages to where you can’t see it on radar.” Up to 150 separate repairs on 30 panels may be required, which takes weeks in air-conditioned bays to bond correctly. This maintenance load is a partial reason the F-22’s mission-capable rate remains around 50 percent.

3. Infrared Signature Suppression

Infrared Search and Track (IRST) sensors, now more commonly installed on enemy fighters, sense heat instead of radar reflections. To defeat this, the F-22 employs flat, two-dimensional thrust-vectoring nozzles that disperse and cool exhaust plumes. The Pratt & Whitney F119 engines are deeply buried in the fuselage, with intake ducts protecting the radar-reflective compressor faces. While this enhances both radar and IR stealth, Lockheed Martin’s use of high-maneuverability nozzle geometry minimally enhances IR visibility from some rear angles a deliberate compromise for dogfight supremacy.

4. Electronic Emissions Control

The AN/APG-77 AESA radar is the focus of the Raptor’s “first-look, first-shot” philosophy. Featuring more than 2,000 transmit/receive modules, it can scan 120 degrees of airspace in an instant, versus 14 seconds for earlier mechanically scanned arrays. Its Low Probability of Intercept mode sends low-power, wideband pulses that are unable to penetrate traditional radar warning receivers. As Northrop Grumman’s Teri Marconi pointed out, this provides “Raptor pilots with access to detailed critical information before the enemy radar ever detects the F-22.” The radar’s SAR and ISAR modes also provide high-resolution mapping and non-cooperative target recognition without compromising the aircraft’s location.

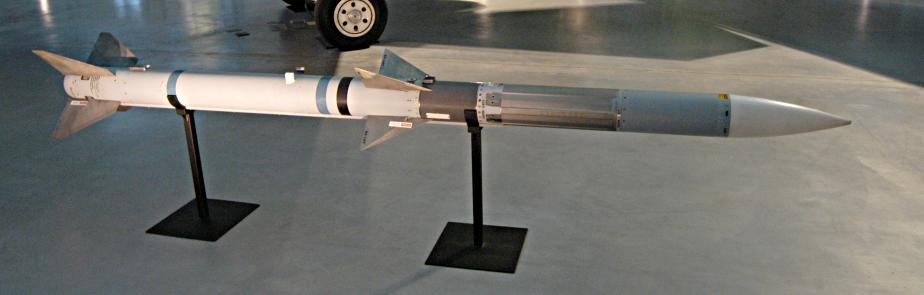

5. Internal Weapons Carriage

External bays are radar beacons. The F-22’s three internal bays maintain its radar cross-section carrying a maximum of six beyond-visual-range AIM-120 AMRAAMs and two AIM-9 Sidewinders. Bay doors open and close in less than one second, reducing exposure. This strategy follows the stealth paradigm now being implemented in designs such as South Korea’s KF-21EX, which is incorporating internal bays in order to survive against contemporary air defenses.

6. Canopy and Acoustic Signature Management

The canopy of the cockpit is gold-coated with a thin film, deflecting radar reflections from the helmet and instrumentation of the pilot. Though less important than radar or IR stealth, the Raptor’s lower acoustic signature, through engine integration and airframe design, provides yet another dimension of detection avoidance, especially against ground-based acoustic arrays.

7. Operational and Maintenance Realities

Stealth is fleeting. Supersonic flight, high-G maneuvers, and exposure to the environment deteriorate coatings fast. Bases in moist, salty environments like Langley suffer accelerated RAM wear and corrosion, whereas desert operations have to fight abrasive sand. Non-combat duties like airshows expose planes to flying with bolt-on radar reflectors at a cost of maintaining combat-coded jets.

8. Role in Modern Air Combat

In a world where IRST-equipped fighter and networked air defenses abound, the F-22’s multi-spectrum stealth remains a game-changer. Against peer threats, it can clear the skies for less-stealthy aircraft, complementing the F-35’s greater data fusion to silence defenses. The combination of shaping, materials, IR suppression, emissions control, and internal carriage enables the Raptor to operate deep within contested airspace, striking before detection.

The stealth of the F-22 is not a one-tech trick but an ecosystem of mutually dependent systems each demanding precision engineering, ongoing maintenance, and operational discipline. As described by one USAF maintenance supervisor, Being invisible is priceless in combat situations.