“Bitterness of poor quality lasts long after sweetness of low price is forgotten.” That time‑honoured saying bears especial weight in the case of firearms, where reliability, safety, and performance are not to be trifled with. And still, the past is full of models that promised heaven but delivered hell, leaving their owners expensive regrets.

In today’s gun industry, engineering restraint can sometimes lag behind the innovations. Designs that promise well on paper or in glossy ads can fail on the battlefield through hasty manufacturing, dubious materials, or design flaws. For both collectors and shooters, learning these lessons is just as crucial as learning which models to look for.

Here’s a closer examination of seven guns that’ve gained notoriety for the disappointment that they’ve brought, whether through repeated failures to function, subpar ergonomics, or reckless safety oversights. Each is a reminder that not every new addition to the safe is worthy of staying there.

1. Remington 710 – A Budget Rifle with Built‑In Compromises

Introduced as an affordable successor to the Model 700, the Remington 710 quickly revealed its shortcomings. Field reports noted a heavy, unrefined trigger, gritty bolt operation, and a plastic stock that flexed under pressure. More troubling was the hydraulically pressed barrel-to-receiver fit, which not only hindered replacement but also compromised long‑term accuracy.

As reported in lengthy owner reviews, the 710 exhibited bolt stop failures, extractor wear that resulted in failure to eject, and soft action rails that gouged as they wore. Although some owners tried aftermarket remedies e.g., replacing the stock or trigger many determined that the rifle’s inherent design problems made it more of an entry‑level filler than a worthwhile investment.

2. Taurus Judge – Versatility That Does Not Hold Up

Promoted as a revolver that could shoot .45 Colt cartridges and .410 shotgun shells, the Taurus Judge was touted for its versatility. Independent testing by firearms instructor Tom Givens, however, showed it to have drastic performance shortcomings. Birdshot loads spat out patterns of over 30 inches at 15 feet, with some pellets not even penetrating an empty plastic bottle. Slugs made primers back out or blow completely off, jamming the cylinder.

Even with specialty .410 handgun buckshot ammunition, useful range was restricted to around seven yards before patterns spread perilously wide. Accuracy with .45 Colt bullets was mediocre, impacted by the extreme bullet jump to rifling. The end result is a gun which, popular as it is, has no obvious benefit over a specialist revolver or shotgun in defense applications.

3. Walther CCP (First Generation) – Innovation Undermined by Safety Recalls

The initial Walther CCP was launched with a gas‑delayed blowback design aimed at minimizing recoil. In practice, it brought with it cleaning difficulties, fouling, and a notoriously fiddly disassembly. More importantly, Walther launched a recall after finding the pistol would fire without the trigger being actuated.

Whereas the subsequent M2 version solved takedown complexity, nothing could revive the first-generation model’s reputation. For the owners who still have one, the maker’s recall warning is still applicable, as the mechanical untrustworthiness coupled with a critical safety flaw makes this model a bad option for any defensive use.

4. Cobray M11/9 – A Weighty Misstep

Following in the MAC submachine gun family, the Cobray M11/9 was a stamped‑steel, blowback-operated 9mm pistol that was ominous in appearance but provided limited useful performance. A bit over four pounds when unloaded, it was unmanageable as a handgun but without the stock and handling of its SMG ancestors.

As observed in various reviews, the M11/9’s massive bolt produces excessive muzzle climb, its crude sights are fixed, and the heel‑type magazine release slows reloads. Reliability degrades with deteriorating Zytel magazines, and even when using better metal substitutes, accuracy is subpar. For the majority of owners, it’s more a curiosity or range toy than a serious handgun.

5. Jennings J‑22 – The Archetype of the ‘Saturday Night Special’

Made between late 1970s, the Jennings J‑22 was a cheap .22 LR pocket pistol that fast gained infamy for being fragile and unreliable. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives named it “extremely dangerous” in a 2001 report, citing the potential for accidental discharge upon falling.

Testing revealed constant stovepipes, double feeds, and ejection failures with all types of ammunition, aggravated by a small ejection port and underpowered extractor. Although mechanically able to deliver fair accuracy from a rest, its 11‑pound trigger and small grip surface discourage practical shooting. Today, it exists largely as a warning example in talks about low‑end pistol design.

6. Remington R51 – A Rebirth That Hurt a Brand

Remington’s effort to update its 1918 Model 51 with the R51 revived the odd hesitation‑locked action, this time in 9mm. The idea sparked interest among enthusiasts, but production failed to live up. Early manufacture firearms had hazardous out‑of‑battery firing, recurring feeding malfunctions, and substandard machining. A recall and introduction of a Gen 2 model lessened some risks but did not address reliability problems.

As chronicled in first-hand range reports, even better models were known to often not fire a full magazine without failure. Ergonomic blunders, such as a grip safety that pinched with recoil, also repelled users. The R51’s bumpy introduction helped sow permanent distrust of Remington’s new product offerings.

7. USFA ZiP .22 – A Futuristic Design That Never Worked

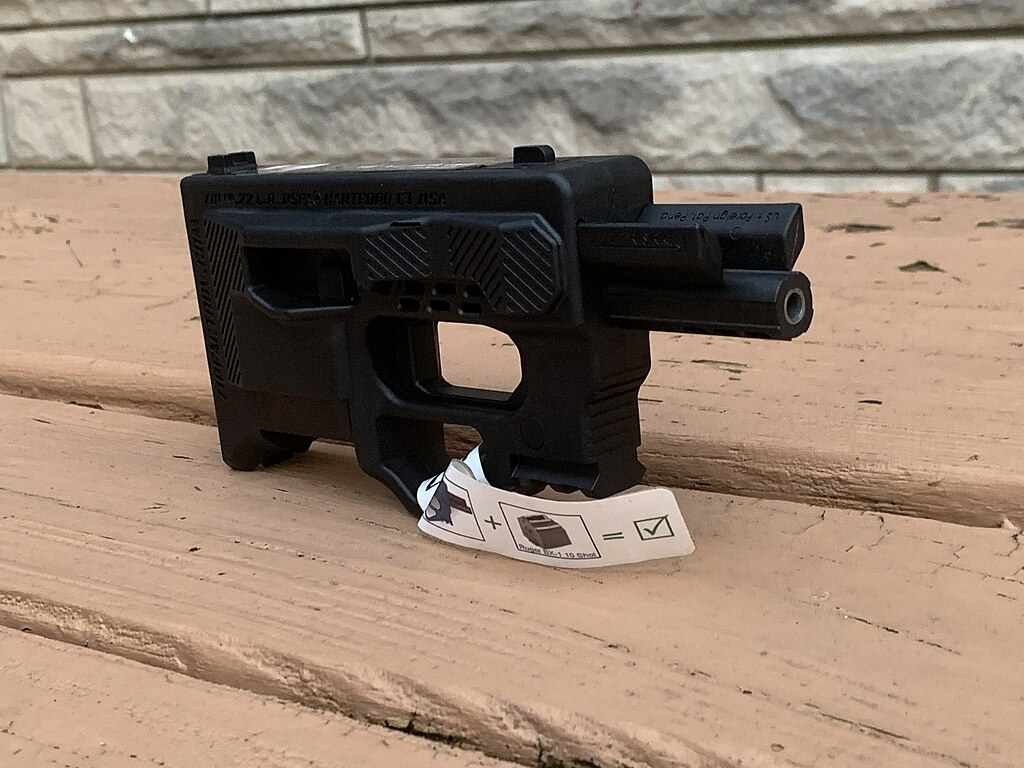

Priced as a budget-friendly, modulized plinker that accepts Ruger 10/22 magazines, the USFA ZiP .22 caused a buzz with its unorthodox bullpup pistol configuration. In reality, it was beset by frequent malfunctions failure to feed, eject, and cycle frequently within the first few rounds of a magazine.

Operators indicated that neither spring replacements nor magazine mods cured the root issue: the plastic bolt cycled too rapidly for consistent feeding. Ergonomics were also flawed with charging handles that were placed perilously close to the muzzle. For all its interesting looks and touted accessories, the ZiP’s almost complete absence of operational reliability made its manufacturer go out of business and only leave a few in circulation, more as curiosities than as guns.

In every one of these instances, charm lies in novelty, price, or utility covered more fundamental design, manufacturing, or quality flaws. For gun owners, the message is clear: strict scrutiny through credible testing, past performance records, and unbiased reviews should come before any purchase. A gun’s real value comes not from its hype, but from its demonstrated capacity to operate safely and reliably when it is most needed.